Researchers Follow a 15th-Century Recipe to Recreate Medieval Blue Ink

The purplish-blue pigment, derived from a Portuguese fruit, fell out of use by the 19th century

:focal(549x314:550x315)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/30/5b302707-6d6a-4db0-a535-cc74350301d7/http___cdncnncom_cnnnext_dam_assets_200416171155-01-blue-medieval-dye.jpg)

In southern Portugal, an unassuming, silvery plant with small, green- and white-flecked fruit grows on the edges of fields and along the sides of roads. But when researchers stirred the fruit—called Chrozophora tinctoria—into a mixture of methanol and water, it released a dark blue, almost purple hue.

Back in the medieval era, the pigment, known as folium, decorated elaborate manuscripts. But by the 19th century, it had fallen out of use, and its chemical makeup was soon forgotten. Now, a team of chemists, conservators and a biologist has successfully revived the lost blue hue. The scientists’ results, published April 17 in the journal Science Advances, detail both the medieval ink’s recreation and the pigment’s chemical structure.

“This is the only medieval color based on organic dyes that we didn’t have a structure for,” Maria João Melo, a conservation and restoration expert at the NOVA University of Lisbon, tells Chemical and Engineering News’ Bethany Halford. “We need to know what’s in medieval manuscript illuminations because we want to preserve these beautiful colors for future generations.”

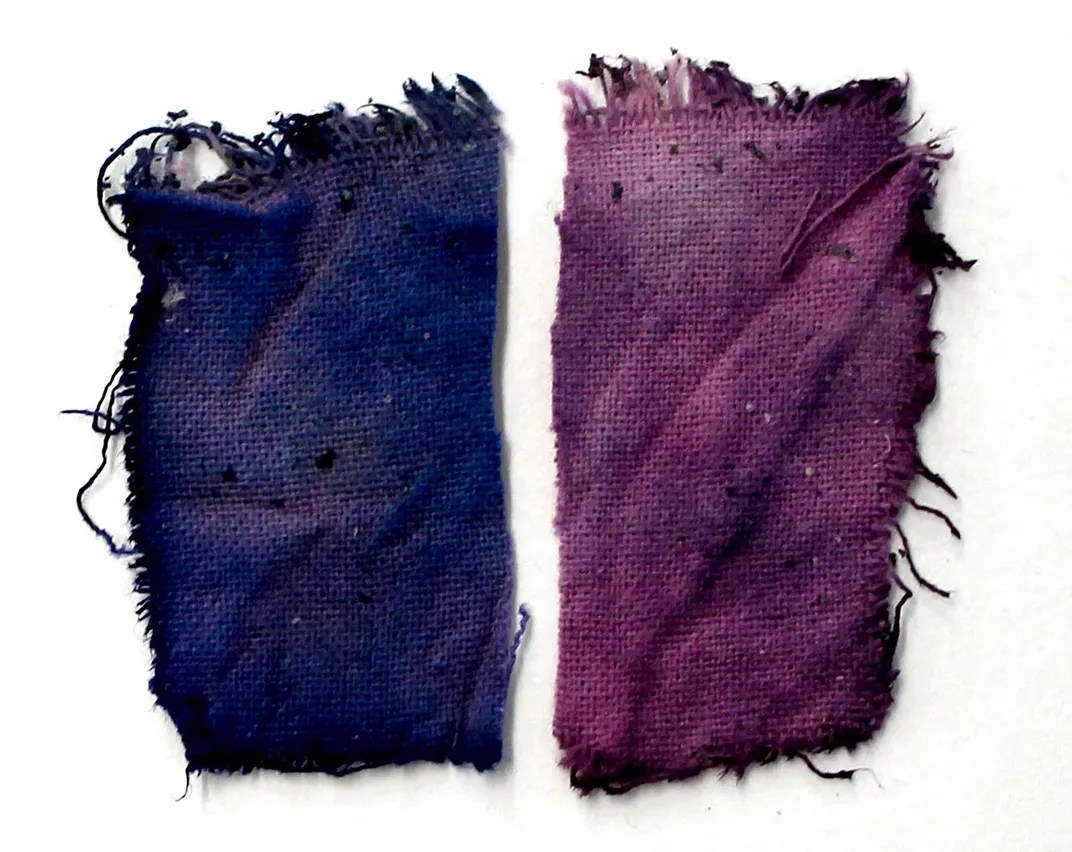

To create folium ink, medieval manuscript makers extracted concentrated pigment from C. tinctoria, soaked a piece of cloth in the purple-blue solution and let the fabric dry. They then reactivated the ink by wetting the cloth.

As Isaac Schultz reports for Atlas Obscura, folium was once used to color everything from illustrations of biblical scenes to the rind of a Dutch cheese. But when medieval manuscripts fell out of use, folium did as well.

The researchers resurrected the pigment with the help of three texts: a 12th-century manual penned by an artisan named Theophilus, a 14th-century painting handbook, and a 15th-century tome titled The Book on How to Make All the Colour Paints for Illuminating Books.

Interpreting these treatises came with its own set of challenges, according to Atlas Obscura. Written in Judeao-Portuguese, an extinct language used by the Jews of medieval Portugal, the trio offered conflicting instructions. Ultimately, the 15th-century text proved indispensable in recreating the ink, Paula Nabais, a conservation scientist and lead author of the study, tells Chemical and Engineering News.

Speaking with Atlas Obscura, Nabais says the manuscript details “how the plant looks, how the fruits look.”

She adds, “[I]t’s very specific, also telling you when where the plant grows, when you can collect it. We were able to understand what we needed to do to collect the fruits in the field ourselves, and then prepare the extracts.”

The books provided detailed descriptions of the plant, which the team’s biologist and expert in Portuguese flora identified as Chrozophora tinctoria. The pea-sized fruits mature in late summer and early fall, so the research team spent July through September 2016, 2017 and 2018 collecting samples to transport back to the lab.

There, the scientists followed the medieval recipe, soaking the fresh fruit in four liters of methanol and water. They stirred the fruit for two hours, taking care to avoid releasing the seeds inside and making the mixture gummy.

“It was really great fun to recover these recipes,” Melo tells Science News’ Carolyn Wilke.

Once the researchers had purified the pigment, they were able to use chromatography, mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance to determine its structure, per Chemical and Engineering News.

Examples of “long-lasting” blue dye are few and far between, according to Science News. Two of the most prominent pigments are indigo, which is also extracted from plants, and anthocyanins, which are found in flower petals and berries. Folium’s blue is in a class of its own, derived from a chemical that the team dubbed chrozophoridin.

As Patrick Ravines, an art conservationist at Buffalo State College who wasn’t involved in the study, tells Chemical and Engineering News, the study highlights “how the combination of historical literature and current scientific methods and instrumentation can sort out with pinpoint precision the chemical nature of the artist’s or scribe’s palette.”