Why Did Ancient Egyptian Scribes Use Lead-Based Ink?

A new study uncovers the science behind ancient writing traditions

:focal(662x501:663x502)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/9d/369d0b1f-14c5-4d75-b2f7-af535414e7fb/redandblackink.jpg)

When ancient Egyptians put pen to paper—or, more accurately, ink to papyrus—they took steps to ensure that their words would endure, a new study suggests.

As detailed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, have found that ancient scribes likely added lead to their inks to help their writing dry.

More than a millennia later, reports Cosmos magazine, 15th-century European Renaissance artists employed lead for similar purposes. According to the London National Gallery, lead-based pigments found in many Old Master paintings are “known to aid the drying of paint films.”

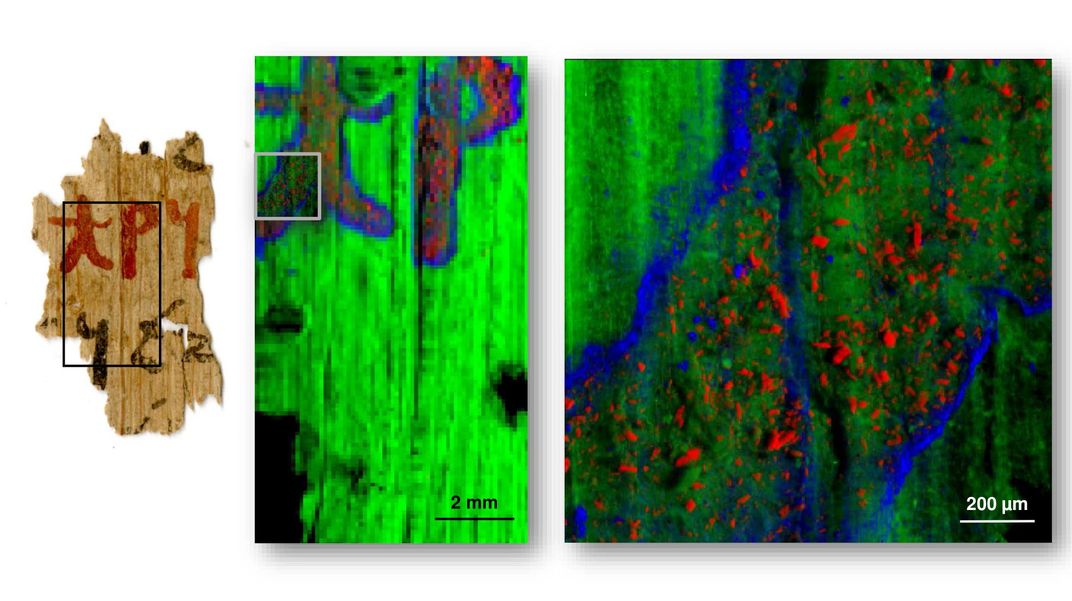

Per a University of Copenhagen statement, the study’s authors analyzed 12 papyrus fragments dated to between 100 and 200 A.D., when Egypt was under Roman control. The team used X-ray microscopy to determine the raw materials used in different inks, as well as the molecular structure of the dried ink affixed to the ancient paper.

Ancient Egyptians began writing with ink—made by burning wood or oil and mixing the resulting concoction with water—around 3200 B.C. Typically, scribes used black, carbon-based ink for the body of text and reserved red ink for headings and other key words in the text, wrote Brooklyn Museum conservator Rachel Danzing in a 2010 blog post. Though black and red inks were most common, shades of blue, green, white and yellow also appear in ancient texts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/26/4a268fa1-d97d-4d79-83dd-12274607627a/city_ajdlkfj.jpg)

The researchers write that the Egyptians created red inks with iron-based compounds—most likely ocher or other natural earth pigments. The team also identified the presence of lead; surprisingly, they found no lead white, minium or other compounds that would typically be present in a lead-based pigment.

Instead, the ancient ink’s lead pigments appeared to wrap around the papyrus’ cell walls and iron particles. The resulting effect looked “as if the letters were outlined” in lead, according an ESRF statement. This find indicates that the ancient Egyptians devised a system of adding lead to red and black inks specifically for the purpose of binding the words to paper.

“We think that lead must have been present in a finely ground and maybe in a soluble state and that when applied, big particles stayed in place, whilst the smaller ones ‘diffused’ around them,” says co-author Marine Cotte in the ESRF statement.

The 12 analyzed papyrus fragments are part of the University of Copenhagen’s Papyrus Carlsberg Collection. The documents originated in Tebtunis, the only large-scale institutional library known to have survived from ancient Egyptian times, per the university statement. According to the University of California, Berkley, which holds a large collection of Tebtunis papyri, many of the ancient texts were excavated from Egypt’s Fayum basin in the early 20th century.

Lead author Thomas Christiansen, an Egyptologist at the University of Copenhagen, notes that the fragments were likely created by temple priests. Because ancient Egyptians would have required a significant amount of complex knowledge to craft their inks, Christiansen and his colleagues argue that ink manufacturing probably took place in separate, specialized workshops.

“Judging from the amount of raw materials needed to supply a temple library as the one in Tebtunis, we propose that the priests must have acquired them or overseen their production at specialized workshops, much like the Master Painters from the Renaissance,” says Christiansen in the university statement.

Christiansen and Cotte previously led University of Copenhagen researchers in a similar study that detected copper in black ink found on ancient papyri. The 2017 paper marked the first time the metal was identified as a “literal common element” in ancient Egyptian ink, as Kastalia Medrano reported for Newsweek at the time.

For the earlier study, the researchers analyzed papyrus fragments, also from the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection, that spanned about 300 years but bore significant similarities in chemical makeup. Those similarities across time and geography suggest “that the ancient Egyptians used the same technology for ink production throughout Egypt from roughly 200 B.C. to 100 A.D.,” Christiansen noted in a 2017 statement.

The team behind the new paper hopes to continue studying the molecular composition of pigments, as well as further investigate the innovative techniques that ancient Egyptians devised.

As Cotte says in the ESRF statement, “By applying 21st-century, state-of-the-art technology to reveal the hidden secrets of ancient ink technology, we are contributing to the unveiling [of] the origin of writing practices.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)