Remains of 9,000-Year-Old Beer Found in China

The lightly fermented beverage contained rice, tubers and fungi

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/59/df5989f8-78c2-471c-bd57-fe2a3f52eec8/pottery_vessels.jpg)

Archaeologists in southeastern China have discovered the residue of beer drunk 9,000 years ago. The vessels containing the ancient dregs were located near two human skeletons, suggesting that mourners may have consumed the brew in honor of the dead, reports Gizmodo’s Isaac Schultz.

The researchers found the Neolithic artifacts at the Qiaotou archaeological site, a circular settlement with a mound in the center located in Yiwu City, Zhejiang Province. They recently published their findings in the journal PLOS One.

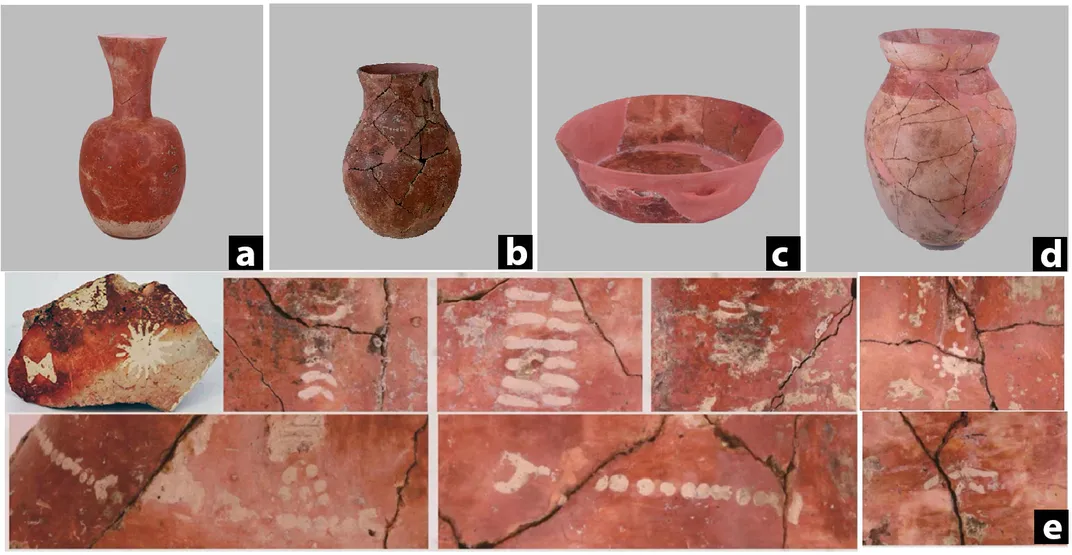

Several long-necked hu pots discovered in pits at the site contained starches, fossilized plant residue and the remains of mold and yeast, indicating that they once held a fermented alcoholic beverage. Hu pots were used for drinking alcoholic beverages in later periods.

“Our results revealed that the pottery vessels were used to hold beer, in its most general sense—a fermented beverage made of rice, a grain called Job’s tears and unidentified tubers,” the study’s lead author, Jiajing Wang, an archaeologist at Dartmouth College, says in a statement. “This ancient beer though would not have been like the IPA that we have today. Instead, it was likely a slightly fermented and sweet beverage, which was probably cloudy in color.”

ScienceAlert’s David Nield writes that archaeologists try to determine the value ancient people placed on particular foods partly by considering how difficult it would have been to collect or produce them. Given the ingredients and the brewing process involved in making the beer, the researchers suggest it may have been part of a burial ceremony.

Qiaotou is one of about 20 archaeological sites in Zhejiang that were part of the Shangshan culture, which researchers believe was the first group to begin cultivating rice, around 10,000 years ago. Per Xinhua, researchers discovered the Shangshan sites, which date back as long as 11,400 years, between 2000 and 2020.

“This place might have been a venue for sacrificial and ceremonial events of the ancient residents," Jiang Leping, a researcher with the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, said in 2014, when excavation at Qiaotou began.

The area around Qiaotou is a big rice producer today, but in 7000 B.C., cultivation of the grain was still relatively new. In addition to using rice grains in the beverage, the brewers appear to have added rice husks, possibly as a fermentation agent. The mold found in the pots would have acted as a starter for the brewing process, though the team says it can’t be sure that the ancient people intended to use it to produce an alcoholic beverage.

“We don’t know how people made the mold 9,000 years ago, as fermentation can happen naturally,” Wang says in the statement. “If people had some leftover rice and the grains became moldy, they may have noticed that the grains became sweeter and alcoholic with age. While people may not have known the biochemistry associated with grains that became moldy, they probably observed the fermentation process and leveraged it through trial and error.”

Another unusual find at the site was the hu pots themselves, as well as other vessels. These are some of the earliest known examples of painted pottery in the world, according to the study. Some were decorated with abstract designs. The researchers said no other pottery of the same kind has been found at other sites from the period.

The Qiaotou beer-making operation wasn’t the world’s first. Earlier examples in the Mediterranean region, including a brew that the ancient Natufians made from wheat, oats, barley and other ingredients in what’s now Israel, date to 13,000 years ago.

Some researchers argue that the production of alcoholic beverages may have helped build social relationships and encourage greater cooperation in ancient times. The authors of the new study say this could have been a factor in the gradual development of complex rice-farming societies over the following 4,000 years in Zhejiang.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)