New Discoveries Double the Size of Ancient Greek Shipwreck Graveyard

Researcher in the Fourni archipelago found 23 ships dating between 525 B.C. and 1850

Last fall, underwater archaeologists rejoiced when it was announced that a joint Greek-American expedition discovered a shipwreck graveyard in the Fourni archipelago in Greece. It was one of the most significant finds of ancient shipping vessels, adding 12 percent to the total number of known ancient shipwrecks in Greek waters.

Now, researchers have reason to keep on celebrating. A second expedition to Fourni last month documented another 23 wrecks, bringing the total to 45. That’s roughly 20 percent of all the pre-modern shipwrecks identified in Greek waters.

“Fourni is certainly an exceptional case. It was a huge shock last season to find so many ships when we expected to find 3 or 4,” expedition co-director Peter Campbell of the RPM Nautical Foundation tells Smithsonian.com. “This season we thought we’d already found the bulk of ships and there must be only 5 or 10 left. When we found 23, we knew it was a special place.”

The project began in summer of 2015 when maritime archeologist and co-director George Koutsouflakis received a call from a spear fisherman, according to Nick Romeo at National Geographic. Manos Mitikas, who had spent years fishing around Fourni, had come across dozens of spots on the sea floor covered in cargo from ancient ships. He had a hand-drawn map of about 40 sites that he wanted to show Koutsouflakis.

In September 2015, aided by Mitikas, the researchers discovered 22 wrecks in 11 days. Returning in June 2016 with a crew of 25 scuba divers and artifact conservators, the team found 23 more wrecks over 22 days, guided to several new locations by fisherman and sponge divers.

So why is Foruni such a hotspot? The set of 13 islands and reefs between the better-known islands of Samos and Ikaria was part of a major Mediterranean shipping route for millennia. The area was known as a safe anchorage for ships, and noted on maps from the Ottoman Empire the Royal Navy as a safe stopping point. Other ancient cultures stopped there too.

“It’s like a maritime Khyber Pass, the only way through the eastern Aegean,” says Campbell. “The number of wrecks is simply a function of the huge volume of trade traffic going through there in every time period. Spread that over the centuries and you have a lot of ships sinking in the area.”

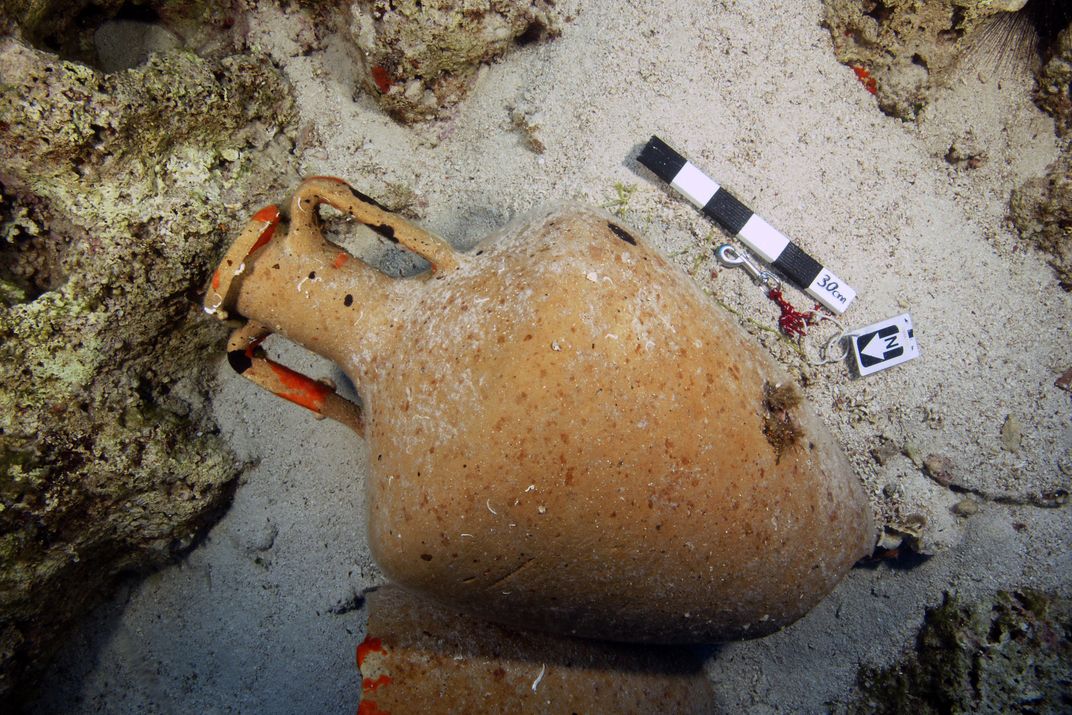

The 45 wrecks span from roughly 525 B.C. to 1850. And while the ships themselves have disintegrated over the years as victims of marine worms, their cargos tell the story. Their loads mainly include amphorae—clay vessels used to transport things like wine, olive oil and fish sauce—identified by their style from Italy, North Africa, Cyprus, Egypt, Spain and elsewhere.

And there’s still plenty to explore. Campbell says the researchers have only surveyed about 50 percent of Fourni’s coastline, and plan to continue surveying the area through 2018. They will also begin deepwater surveying using multi-beam sonar since much of the coastline is made of cliffs that drop quickly to 1,000 feet and may be hiding many more wrecks.

Currently, when divers locate a wreck in coastal waters, the site is photogrammetrically scanned to create a 3-D image. Divers then bring up representative artifacts from the cargo. Those are preserved on site and will later be tested for their origins, contents and possibly for DNA at a conservation lab in Athens. Any wrecks of particular importance will undergo further excavation once the initial survey is complete.

Already, Campbell has his eye on several wrecks. There are at least two from the second century A.D. carrying goods from the Black Sea area that contain amphora known only from fragments previously found on land. He’s also interested in several very rare wrecks dating from 525 and 480 BC, Greece’s Archaic period. At another site, he says they found fragments of famous black-glazed pottery made by the Hellenistic Greeks that an octopus had pulled into an amphora to make a nest. He’s hoping that wreck will yield some of the rare tableware.

But the most significant part of the expedition has been the involvement of the local community, which many expedition teams ignore or are hostile toward researchers. In Fourni, Campbell says the locals are taking a keen interest in their history, and their tips are what has made the expedition a success. “Of the 45 wrecks, we found about 15 from our systematic survey of the coast, and the rest have come from local reports,” he says. “We could have found them all just doing our survey, but it would have taken us 10 years. We’ve spent way less money, spent more time talking and found way more wrecks.”

The team plans to head back to Fourni, likely next June, to continue their survey. Campbell says it’s very likely that they’ll have several more seasons finding 20 or more wrecks in the archipelago.