When Deborah Willis was growing up, her teachers seldom mentioned the black soldiers who’d fought in the American Civil War.

Years later, when the Philadelphia native became a curator—working first at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and then at the Smithsonian Institution—she found herself intrigued by photographs of these individuals, whose stories are still so often overlooked.

Speaking with Vogue’s Marley Marius, Willis explains, “I was fascinated because we rarely see images of soldiering, basically, with the backdrop of portraits.”

As Nadja Sayej reports for the Guardian, the scholar and artist’s latest book, The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship, commemorates the conflict’s military men and women through more than 70 photographs, handwritten letters, personal belongings, army recruitment posters, journal entries and other artifacts.

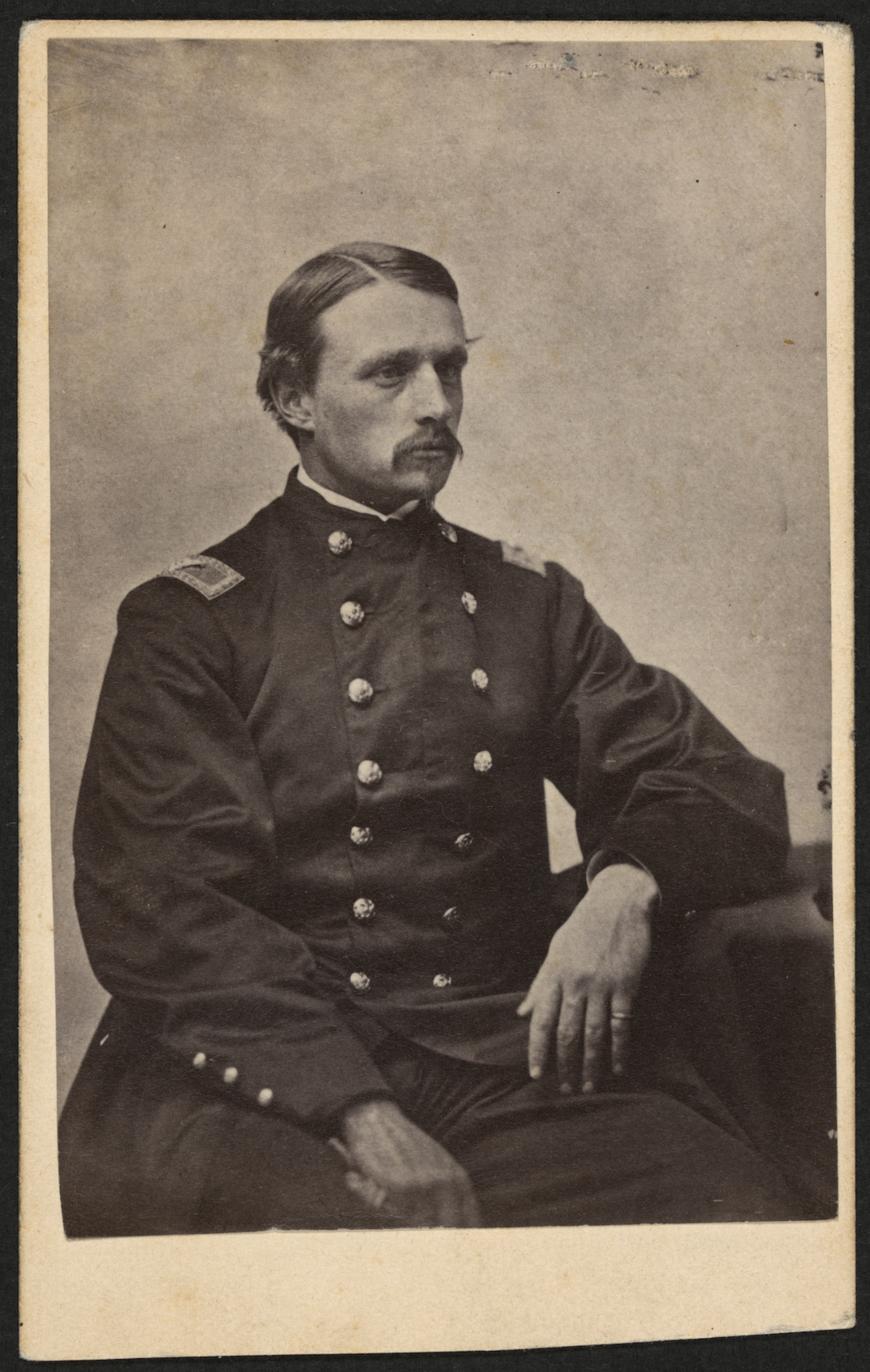

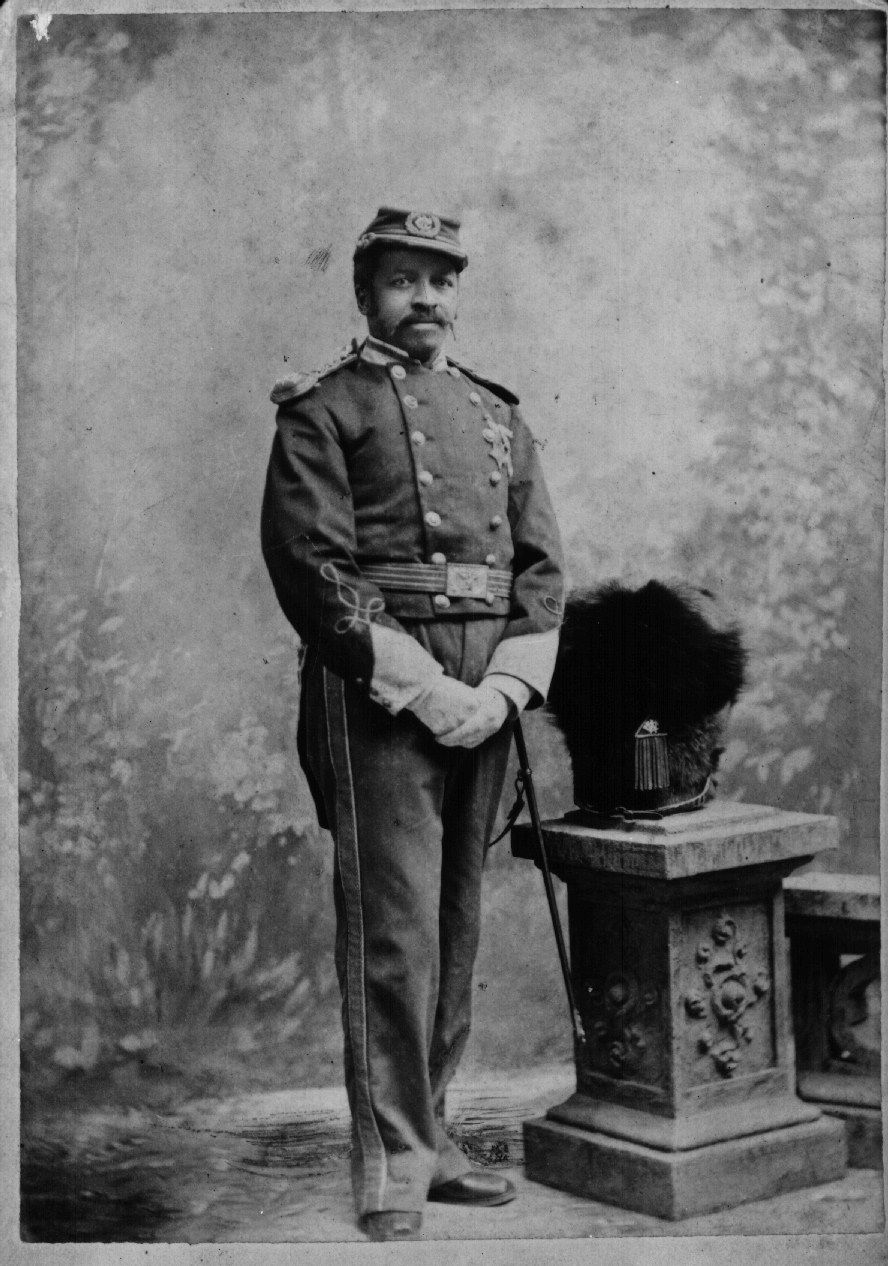

Posing for portraits allowed black men who’d long been “told that they were second-class citizens, that they were subhuman,” to assert their newfound identity and freedom as soldiers, Willis tells Vogue.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/1a/9c1ae8eb-8bc2-4249-b1ef-174c884f20ec/screen_shot_2021-01-29_at_51545_pm.png)

“Having a photograph taken was indeed a self-conscious act, one that shows the subjects were aware of the significance of the moment and sought to preserve it,” the author writes in the book’s introduction. “Photographs were a luxury; their prevalence shows their importance as records of family, position, identity, and humanity, as status symbols.”

Many of the images in The Black Civil War Soldier depict their subjects in uniform, donning military jackets and belt buckles while carrying rifles or swords. On the book’s title page, for instance, Alexander Herritage Newton, a sergeant in the 29th Connecticut Infantry, poses alongside Daniel S. Lathrop, who held the same rank in the same regiment.

The two stand side by side, holding swords in their gloved hands. Hand-colored after the portrait sitting, the men’s gold jacket buttons and belt buckles, green sleeve chevrons, and purple belt tassels appear in sharp contrast to the rest of the black-and-white photograph. (Soldiers paid extra for these touches of color, which added a level of verisimilitude to the keepsakes.)

Per the Guardian, black and white soldiers alike often posed for tintypes—an early, relatively inexpensive form of photography that allowed artists to shoot outside of the studio—in order to send the likenesses to their loved ones.

Willis uses letters and journal entries to offer a sense of the photographed soldiers’ personalities. As she notes, these writings “convey the importance of family and family ties, the urgent need to belong.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/47/2547eeba-8069-47f9-9b36-de61413eb2b3/willis_36.jpg)

Some missives discuss principles of equality, while others outline their authors’ reasons for joining the war effort.

Newton, the sergeant pictured on the book’s title page, penned a letter stating, “Although free born, I was born under the curse of slavery, surrounded by the thorns and briars of prejudice, hatred, persecution.”

A number of black soldiers wrote to President Abraham Lincoln directly, pledging their allegiance to the war effort and offering their services. Others’ mothers petitioned the president to ensure that their sons received equal pay and treatment.

“By examining diary pages, letters and news items, I want to build on the stories that each of their portraits tell,” Willis says to the Guardian, “to focus a lens on their hopefulness and the sense of what could be won from loss.”

The Civil War was rife with such loss. An estimated 620,000 soldiers died during the war, making it the bloodiest conflict in American history. Though black Americans weren’t initially allowed to fight, this changed with the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. In May of that year, per the Library of Congress, the U.S. government established the Bureau of Colored Troops to oversee rising numbers of black recruits.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/fe/01fe7a7e-c09f-4032-9d9f-9a78b15d7616/soldier_1.png)

According to the National Archives, roughly 179,000 black men, or ten percent of the Union Army, served as U.S. soldiers during the Civil War. (Another 19,000 enlisted in the U.S. Navy.) Approximately 30,000 of the nearly 40,000 black soldiers who died in the line of duty succumbed to infection and disease—a fact that underscores the importance of oft-unrecognized non-combatants like cooks, nurses and surgeons, Willis argues.

“The role of sanitation and cleanliness and health is a quiet story,” the scholar tells Vogue. “Most of the men died because of unsanitary conditions, and the role of women was to clean the wounds, clean the clothes.”

In a January 27 livestream hosted by the National Archives, Willis said she hopes that her book can help people re-examine representations of the Civil War by telling stories about its forgotten figures.

“These [are] fantastic works by the photographers, as these artists knew the importance of, the worthiness of these soldiers and fighters and cooks and nurses,” she explained, “the sense of what it meant to be free and what it meant to personalize their experience through the visual image.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/cd/32cd8d69-7067-4ab6-9ee8-e737593a6769/willis_25.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/f2/2ef29481-1e66-4a92-8872-ef61564f2cd4/willis_40.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/bf/95bfeec2-0364-493f-a19f-a3780e699231/willis_54.png)

:focal(274x140:275x141)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/4f/f64f2a06-3dea-43f6-9c69-5462ecc3c11a/black_soldiers_mobile.jpg)

:focal(392x209:393x210)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/8a/f98a0f70-b6d2-4e39-ac0f-90bd22246b52/social_soldiers.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)