Why the Legend of Medieval Pope Joan Persists

The mythical female pope is back in the news as an academic uses medieval coins to look for physical evidence of her reign

:focal(617x274:618x275)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/31/42316f27-8c11-4a75-935d-ab967ebe2049/pope-johanna.jpg)

In the late Middle Ages, a popular legend advanced the story of a medieval woman who disguised herself in men’s clothing and ascended to the role of pope. A dramatic ending to the tale ensured its endurance: As the woman, masquerading as Pope Johannes Anglicus, led a religious procession through Rome during the mid-ninth century, she allegedly went into labor, exposing the fact that “Johannes” was actually “Joan.”

While most historians believe Pope Joan is nothing more than a myth invented by early critics of the Catholic Church, her story has proven too tantalizing to be forgotten. Over the years, various researchers have attempted to find a real, historical Joan. The latest is Michael E. Habicht, an archaeologist at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia.

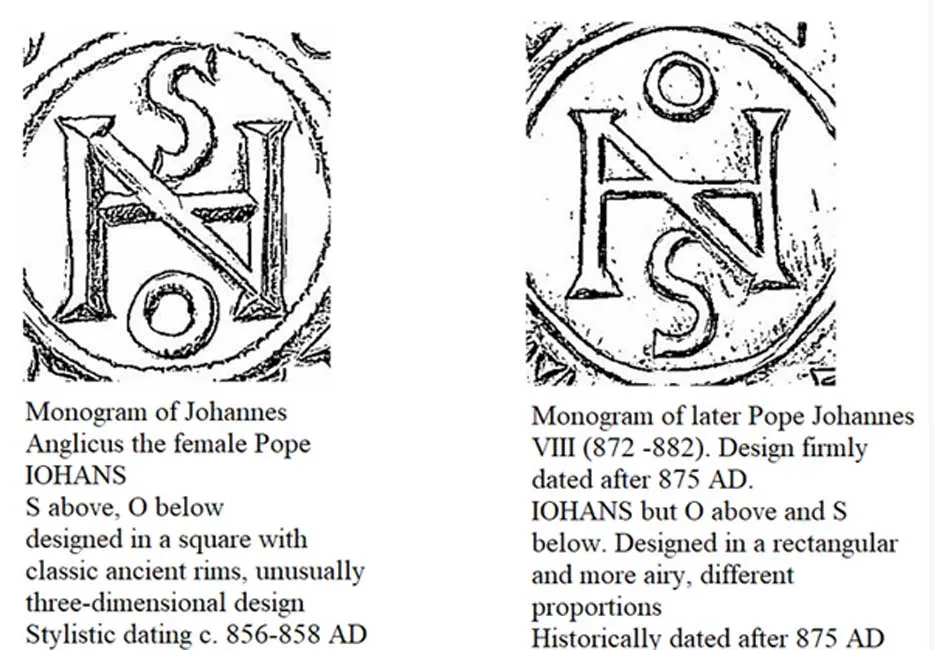

Live Science’s Charles Q. Choi reports that Habicht and co-researcher grapho-analyst Marguerite Spycher analyzed papal monograms emblazoned on medieval coins known as deniers to determine if they revealed any physical evidence for Joan’s reign.

Looking at coins attributed to Pope John VIII, who reportedly reigned from 872 to 882, he and Spycher found that those minted earlier bore a markedly different monogram than those minted toward the end of his reign. Habicht doesn’t view these distinct designs as mere human error: Instead, he argues that the earlier monogram, which dates from 856 to 858, belongs to Johannes Anglicus, or Joan, while the latter belongs to John VIII.

Habicht proposes that Joan’s brief reign was thus squeezed in between Benedict III and Nicholas I, who served as heads of church between 855 to 858 and 858 to 867, respectively, according to a generally accepted timeline of Catholic popes.

According to a press release, Habicht and Spycher’s research is currently being translated into English from a recently released German version, entitled Päpstin Johanna: Ein vertuschtes Pontifikat einer Frau oder eine fiktive Legende?, published by Verlag, Berlin.

Bry Jensen, co-host of the papal-centric Pontifacts podcast (which is readying to do an episode on Joan), describes the new findings as “intriguing” but remains unconvinced of Joan’s existence. At the height of the myth’s popularity, fabricated relics were prized commodities, raising the possibility that a devious craftsmith coined fake deniers referencing the legendary female pope. Although Habicht debunks the possibility of forgery, noting that contemporary demand for medieval coins is not strong enough to warrant such deception, Jensen argues this explanation fails to account for medieval forgeries.

According to a British Library blog post written after Rihanna donned papal mitre for the 2018 Met Gala, the first direct mention of Joan appears some 300 years after the female pope was claimed to have lived—a lapse in time that Jensen cites as “the ultimate red flag.”

She adds, “The further a ‘first source’ is from the actual period it is said to happen, the less reliable it should be considered.”

The Chronicle of Popes and Emperors, a 13th-century text composed by Dominican monk Martinus Polonus, is considered to have birthed the most well-known narrative of the Pope Joan story. Polonus includes an array of details, from Joan’s birthplace to the length of her reign and place in the pontificate timeline, but writes in a “tone of uncertainty” suggesting he is skeptical of the tale’s veracity, Ancient Origins notes.

Most historians (and the contemporary Catholic Church) dismiss the tale of the female pope as wishful thinking. In an interview with ABC News, Southern Methodist University medieval scholar Valerie Hotchkiss explains that medieval monks likely passed down exaggerated accounts of Joan’s life, “picking [them] up from each other and changing and embellishing [them].”

The implications of Joan’s story, whether fictional or real, reveal much about the early church’s dismissive attitude toward women. Such attitudes linger to this day, with Live Science’s Choi noting that the Catholic Church still prohibits women from becoming ordained.

That might be why, to date, more than 500 historical texts have been compiled on Joan’s life, Donna Cross, author of the 1996 novel Pope Joan, tells ABC News.

Nevertheless, the evidence refuting Joan's historical existence adds up. “No source outside of the Catholic Church until the Protestant Reformation references the existence of a female pope,” Jensen says. “Even the enemies of the Church seem silent on this, despite the perfect opportunity to denounce the church.”

So, what happened in the story after Joan was unmasked? As Evan Andrews writes for History.com, some suggest the female pope died in childbirth, while others paint a far bloodier picture of the scene, asserting that the angry crowd stoned Joan to death—but almost all versions of the tale concede that Joan’s brief reign ended the day of the doomed procession.

It’s unsurprising that her legend wields such staying power today: “It has every element of a tantalizing tale,” Jensen says, “[from] turning a system of rigid oppression on its head [to] a brilliant woman who equaled or bested her male counterparts."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)