Rare Book Library Summons Tales of World’s Oldest Monsters

The monsters have arrived at Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/6f/4c6fa82d-bdda-4a59-9f9d-acb27edec87d/monstermash.png)

In December 1495, Rome was devastated by four days of heavy flooding. After the deluge subsided, rumors began to swirl about a terrible monster that had washed up onto the banks of the Tiber. The creature was said to be a grotesque pastiche of human and animal body parts: it had, among other peculiarities, the head of a donkey, the breasts of a woman, the bearded visage of an old man on its behind, and a tail crowned with a roaring dragon’s head.

This was the era on the cusp of the Reformation, and many were convinced that the monster had been conjured as an ominous portent of papal corruption, with each of its hodge-podge body parts representing a different vice. (The creature’s “feminine” breasts and belly symbolized “the sensuality of the cardinals and ecclesiastical elites”; the old man on its hind parts marked a “dying regime.”) Printed images of the so-called “Papal Ass” were circulated widely in the years after the flood. Martin Luther, the father of Protestantism, even commented on the monster in his railings against the Catholic Church.

The "Papal Ass" is just one of many strange, unsettling creatures to appear in the pages of centuries-old texts now on display at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in Toronto. Just in time for Halloween, the library has launched De Monstris, an exhibition that explores the rich tradition of monstrous beings that have stoked fears and tickled imaginations throughout history.

“Monsters are an integral part of our shared cultural heritage,” David Fernandez, the curator of the exhibition, tells Smithsonian.com.

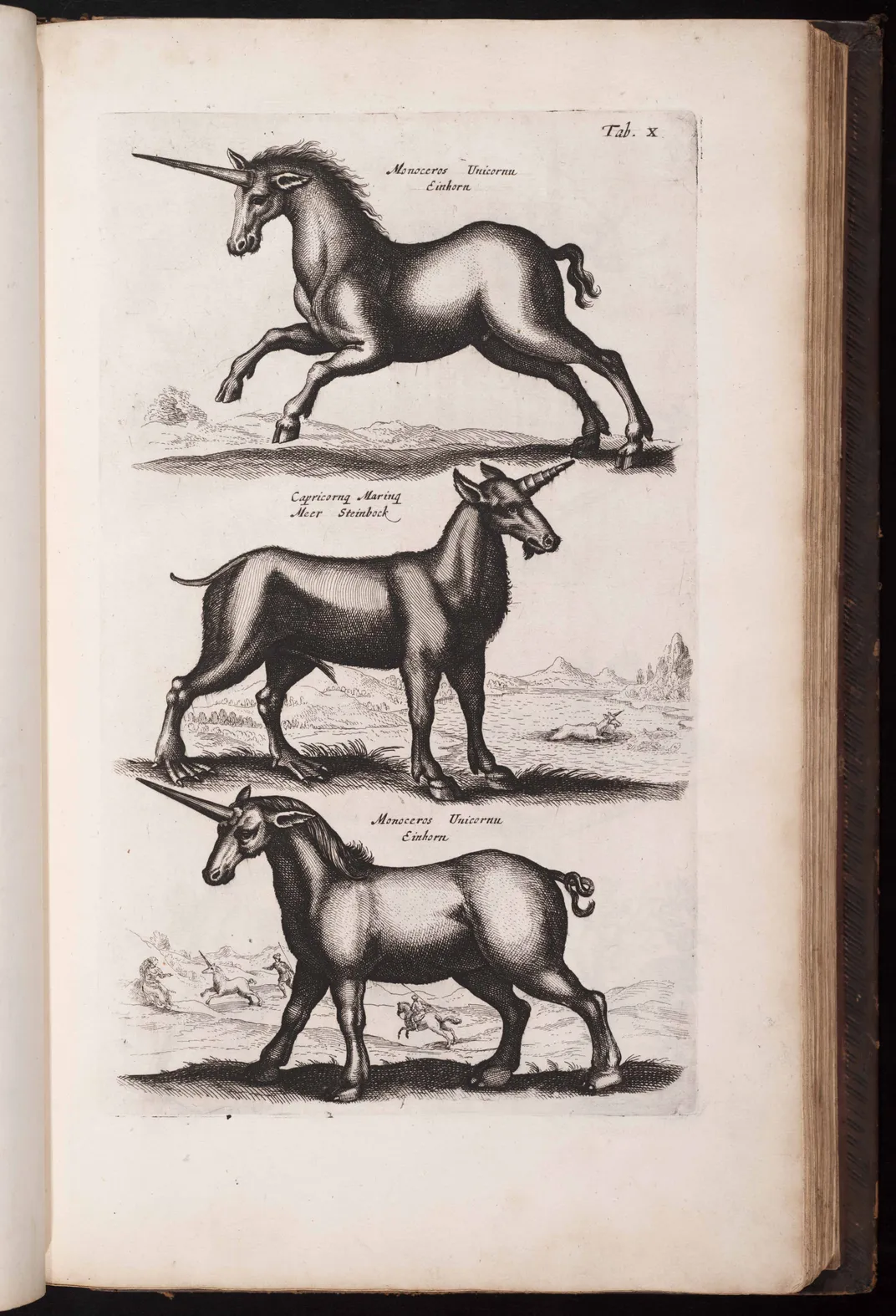

De Monstris spans a vast period of time, linking lore from antiquity to the Middle Ages, and on through the 19th century. The show features writings by the likes of Marco Polo, Sir John Mandeville and Mary Shelley. Also on display are vivid illustrations of dragons and basilisks, unicorns and Cyclopes, mermaids and manticores, and more obscure hybrid creatures, such as a historic rendering of the Papal Ass, published in 1545.

“It's extremely scarce,” Fernandez stresses of the manuscript. “That particular sheet survived in a binding from the 16th century—after the binding was cut open, that's what they found. Can you imagine?”

Fernandez first became interested in the history of monsters while pursuing his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. He took a course on Portuguese expansion into Africa and the Americas, and was surprised to find that many exploration narratives from the period described strange and fantastical creatures amidst foreign landscapes. Later, as a librarian at the Thomas Fisher library, Fernandez was once again taken aback to learn just how longstanding and pervasive the tradition of writing about monsters was.

“I realized that we have a lot of books that you wouldn't necessarily associate with monsters,” he says, “and authors that are part of the canon of Western culture and literature explored ideas of monstrosity and reported monsters in different traditions and genres.”

For instance, Aristotle's expansive biological text, the Book of Animals, posits that a pregnant woman can impress monstrous features onto her unborn child just by looking at an image of a monster. A 15th-century edition from Venice is on view in the exhibition, and according to Fernandez, the philosopher's ideas persisted for hundreds of years.

Many books about monsters, in fact, drew on tropes that were recycled across centuries. When the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote about “tribes of human beings with dogs’ heads,” his descriptions of these bizarre hybrids were preserved in manuscripts, parroted in medieval encyclopedias and referenced in Renaissance texts. By the 16th-century, German cartographer Sebastian Münster noted skeptically in his pictorial encyclopedia Cosmographia that “the ancients have devised peculiar monsters … but there is nobody here who has ever seen these marvels.” And yet, a 1559 edition of the Cosmographia contains a woodcut illustration of a dog-headed man.

Writers felt compelled to nod to previous descriptions of monsters in part so they could flaunt their scholarly knowledge. “If you're telling, for example, a history of serpents, you have to include dragons, because up to that point, that was part of the tradition,” Fernandez explains. Monsteres were also a sure-fire way to attract an audience; like many of us today, readers of the past were fascinated by weird and wondrous creatures, which is why so many of the texts on display were paired with illustrations.

Whether people believed that monsters really existed is a different question. “A lot of the authors don't claim to believe in the monsters, but they still use them,” Fernandez notes.

When assembling materials for De Monstris, Fernandez let his sources define the parameters of what constitutes a monster. And so an entire section of the exhibition deals with “monstrous” bodies—congenital abnormalities that were particularly fascinating to writers of the 18th and 19th centuries. Another section focuses on letters, journals and cartographic material from the Age of Exploration, when Europeans came into contact with the New World. These accounts are rife with wild descriptions of mermaids, sea monsters, one-eyed humans and nations made up of headless people. At times jarringly prejudicial, these texts sought to analyze the people of foreign lands—and set them apart from a European audience.

"The history of every civilization is the history of encounters," Fernandez says, pointing to an illustration from a 17th-century travel book, which showed a furry, human-like creature being captured by the Tupinambá people of present-day Brazil. "Our own cultures are produced by our own realities, but also by encountering the realities of other peoples in other regions of the world."

A shift in focus is evident among the objects featured in the last section of De Monstris, which centers on literature of the 19th and 20th centuries. During this time, Fernandez says, scientific thinkers started to rely less on textual traditions and more on empirical evidence, but monsters were deployed as potent symbols by fiction writers. On display at Thomas Fisher are early editions of works like Frankenstein, The Picture of Dorian Grey and Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde—novels that use monsters not to explore the frightening nature of the Other, but to reflect on the capacity for evil and harm that resides within the self.

This year happens to mark the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s canonical cautionary tale about overstepping the bounds of science and technology. The exhibition highlights an 1882 edition of the work, which was printed before Shelley's creature was transformed into the green-skinned, square-headed anomaly of modern popular culture. This early edition instead stays true to Shelley’s portrayal; on the cover of the book, the monster is depicted as an exceptionally tall man, a menacing mirror image of the doctor who created him.

In the interest of keeping the exhibition focused on historical portrayals of monstrosity, Fernandez did not include materials published beyond the early 20th century. But creepy creatures and fantastic beasts remain ever present in our imagination—the latest chapter in a vibrant, complex history of storytelling.