A British Jail Is Paying Artistic Tribute to Oscar Wilde, its Most Famous Inmate

Patti Smith, Ai Weiwei and others envision what it’s like to be Inside

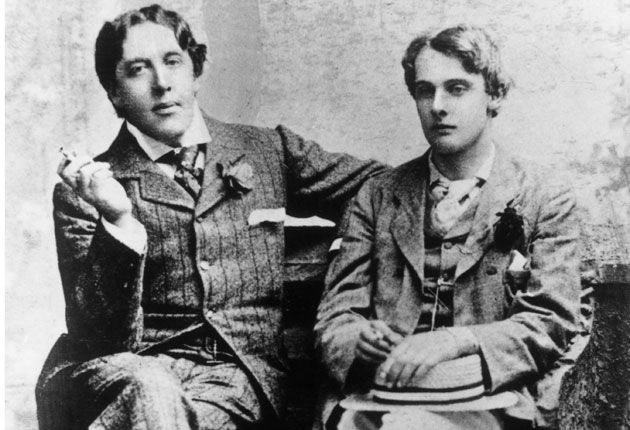

Oscar Wilde was known for his boundary-pushing prose and his out-there public behavior, but society refused to tolerate the fact that he was openly gay. At the height of his popularity, Wilde was thrown into jail for his homosexuality—an act of revenge that broke his health and changed the course of the rest of his life. Now, reports Farah Nayeri for The New York Times, the place where he served a hard labor sentence for two years is commemorating its most famous inmate with a series of events that examine Wilde’s extravagant legacy through art.

The event, Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, brings famous artists like Ai Weiwei, Patti Smith and Nan Goldin inside the jail. As Nayeri reports, visual art is hung throughout the prison’s cells and hallways, and a limited number of visitors can walk the halls in silence as they listen to related readings and explore the never-before-open-to-the-public prison. The exhibition digs into the isolation and pain of Wilde’s imprisonment and those of others who are denied personal autonomy and freedom. Other events, like weekly six-hour readings from Wilde’s De Profundis by famous actors like Ralph Fiennes, bring Wilde’s ordeal to life in the context of his art.

Known as Reading Gaol, the facility in Reading, England, where Wilde was imprisoned was in operation from 1844 to 2013. Though its lack of modern facilities was what forced its closure, at the time of its opening in the mid 19th century, the jail was hailed as a thoroughly modern facility. Boasting individual cells that kept prisoners separate from one another, it was an example of the newfangled “separate system” that flourished among prison reformers of the 19th and early 20th century. Designed to try to force prisoners to think about their crimes and rehabilitate, the separate system was first developed in the United States and exported around the world as an example of the latest in prison philosophy.

Oscar Wilde's #DeProfundis read in its entirety. 6 hours, 12 minutes, no breaks: https://t.co/jS7P1lEUpt pic.twitter.com/i1NnvZLoIq

— Artangel (@Artangel) September 12, 2016

Wilde came into the brutal system during the peak of his career. As audiences delighted at the first stage production of The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde began to fight a legal battle against the Marquess of Queensberry, whose son Lord Alfred Douglas was in a relationship with Wilde. Desperate to break up the relationship, the Marquess set out to ruin Wilde’s reputation, spreading rumors that he engaged in “indecent” activities. When Wilde fought back, filing a charge of libel, it backfired and during the trial, his homosexuality entered into testimony. At the time, engaging in homosexual acts was against the law—even when the sexual contact took place consentingly. Queensberry informed Scotland Yard of Wilde’s acts and he was put on trial and convicted for “gross indecencies.”

Inside Reading Gaol, Wilde was horrified by the sanitary conditions, driven mad by his solitude and indignant at his treatment. He spent 18 months of a two-year jail term there. Two of his most famous works emerged from that time in jail: The Ballad of Reading Gaol, which he wrote after leaving the country once his jail time was up, and De Profundis, a long, searing letter to Douglas that was published after his death. Wilde emerged from prison haunted, unhealthy and bankrupt, and died in exile just three years later. He was just 46 years old.

The show, which is being put on by heralded art events organization Artangel, is already being hailed as “momentous.” “How Oscar Wilde would have loved it,” writes The Guardian’s Laura Cumming. That he was imprisoned because of whom he did love is, of course, part of the irony that makes the exhibition even more profound.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)