The Antiquarium, a museum located on the ruins of the ancient city of Pompeii, fully reopened this week for the first time in more than 40 years.

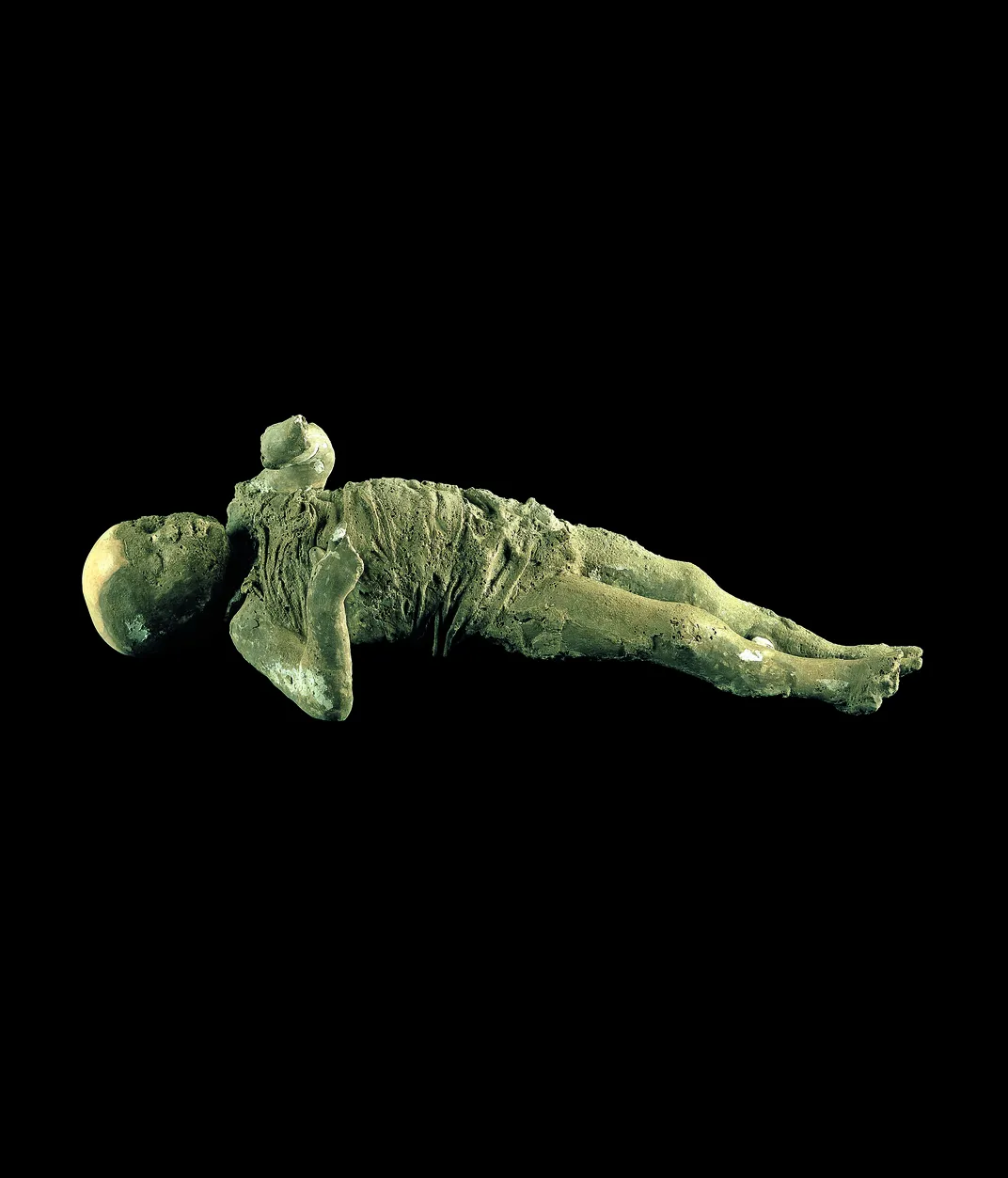

Home to some of the razed settlement’s best-preserved artifacts, including protective amulets and plaster casts of Mount Vesuvius’ victims, the museum will host a permanent display narrating Pompeii’s history, reports Hannah McGivern for the Art Newspaper.

As Massimo Osanna, director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, tells the Associated Press’ Andrea Rosa, the opening is “a sign of great hope during a very difficult moment” for Italy’s tourism industry, which has shrunk significantly during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Per a statement, the Antiquarium offers “an introduction to the site, … told through the most significant artifacts of the ancient city, from the Samnite era [of the fourth century B.C.] to the tragic eruption of 79 [A.D], with particular attention paid to the city’s inseparable link with Rome.”

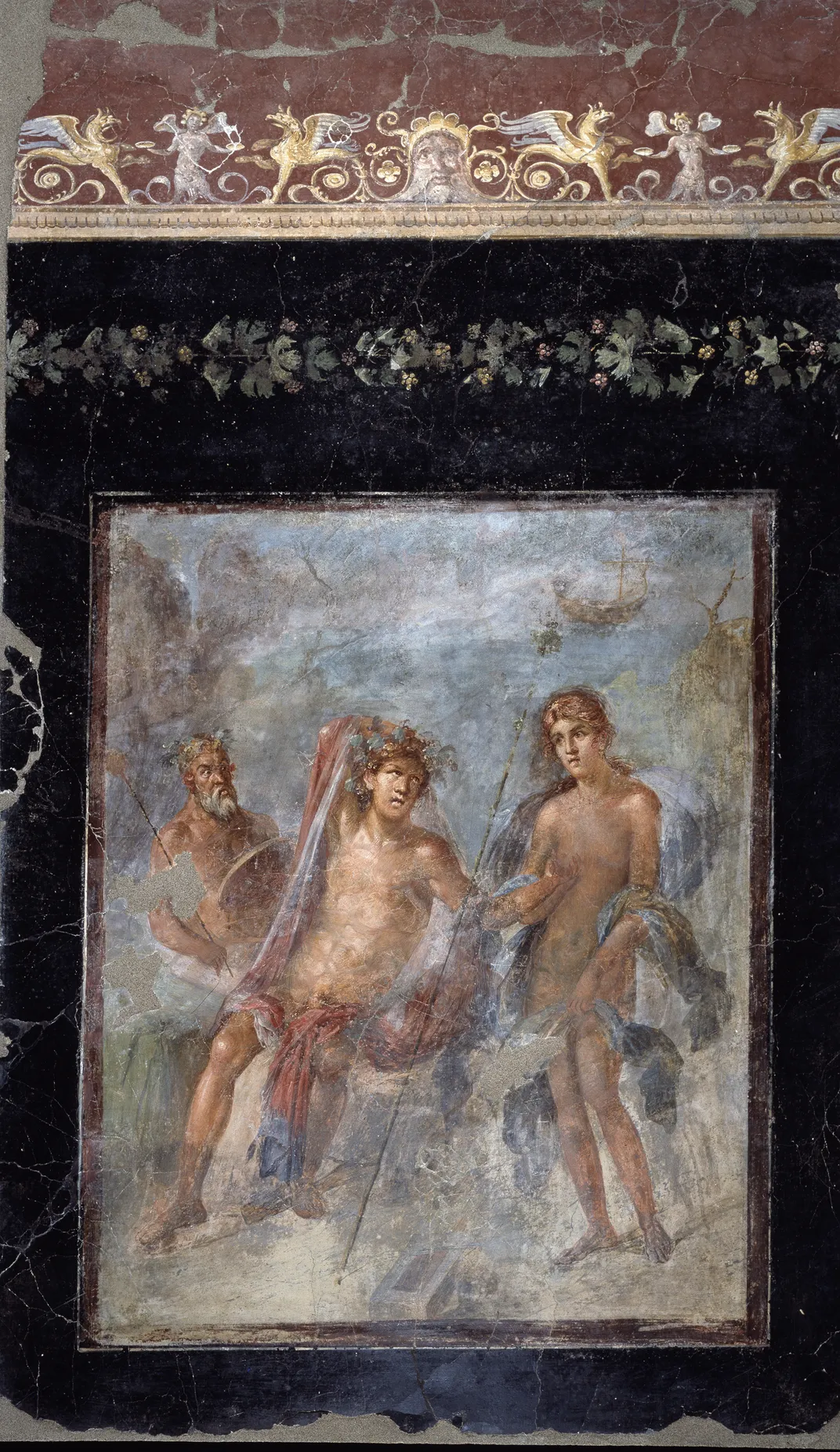

Exhibition halls will feature walls adorned with frescoes and graffiti, household objects like a bronze food-warmer and tableware, and marble and bronze statues, among other archaeological treasures.

“I find particularly touching the last room, the one dedicated to the eruption, and where on display are the objects deformed by the heat of the eruption, the casts of the victims, the casts of the animals,” Osanna tells the AP. “Really, one touches with one’s hand the incredible drama that the 79 A.D. eruption was.”

The museum, dedicated to one of the most well-known disasters in history, has endured its own fair share of destruction. According to Wanted in Rome, the Antiquarium first opened around 1873. During World War II, bombs destroyed an entire room and hundreds of artifacts. Though the museum reopened five years later, in 1948, the 1980 Irpinia earthquake forced it to close once again. Since 2016, the space has opened for several temporary exhibitions, but it is only fully reopening now.

Pompeii is the most-visited archaeological site in the world, notes Italy's tourism agency, but in recent years, visitors to the razed city haven’t been able to see many some of the significant finds recovered during excavations.

“For security reasons they were held in our storage rooms,” Luana Toniolo, an archaeologist and head of the Antiquarium, tells the Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA).

The newly refurbished museum will offer context for artifacts like a rare silver dining set known as the Moregine Treasure and jewels found at the House of the Golden Bracelet, a luxuriously decorated villa where archaeologists discovered frescoes, mosaics and the preserved bodies of numerous victims. The displays will feature chat bots acting as virtual guides to the items, according to a separate statement.

Researchers estimate Pompeii’s population at the time of the eruption at 12,000. Most of these residents escaped the volcano, but around 2,000 people in Pompeii and the neighboring city of Herculaneum succumbed to pyroclastic flows and poisonous fumes.

Pompeii’s extraordinary preservation has made it a subject of interest for researchers for centuries. The first systematic excavation of the site began in 1738, when archaeological science was in its infancy. Work continued in starts and stops. By the 1990s, about two thirds of the city had been excavated. But the site suffered lasting damage from illegal treasure hunters and early archaeological work that was not up to modern standards.

As Osanna told Smithsonian magazine’s Franz Lidz in 2019, excavations led by his predecessor, Amedeo Maiuri, in the mid-20th century were highly productive but left their own puzzles for modern researchers.

“He wanted to excavate everywhere,” Osanna said. “Unfortunately, his era was very poorly documented. It is very difficult to understand if an object came from one house or another. What a pity: His excavations made very important discoveries, but were carried out with inadequate instruments, using inaccurate procedures.”

A roughly $140 million restoration project launched at the site in 2012 has filled in many of the gaps in archaeologists’ knowledge. Specialists in topics from bricklaying to biology have found new clues about the ancient city using tools including CAT scans and drone videography. Among the most important finds from recent years is a charcoal inscription apparently made just before the city’s destruction; the text suggests that the eruption occurred in late October of 79, not in August as historians had long thought.

With the reopening of the Antiquarium, the public will now be able to see some of the remarkable items discovered at the site for themselves.

“Pompeii finally has a museum, and it is a unique one,” Osanna tells ANSA.

:focal(297x162:298x163)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/9e/d19e8767-f46d-4c61-ae27-69baf09f1266/mobile_statue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/f6/fdf65a79-1146-46f9-b00d-b451aed44127/social_pompeii.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)