This 17th-Century Anatomist Made Art Out of Bodies

Using human bodies in this way still happens–and it’s controversial

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/47/0f4798fe-493b-49da-9138-51f1f5dc9263/i-c-1-03-wr.jpg)

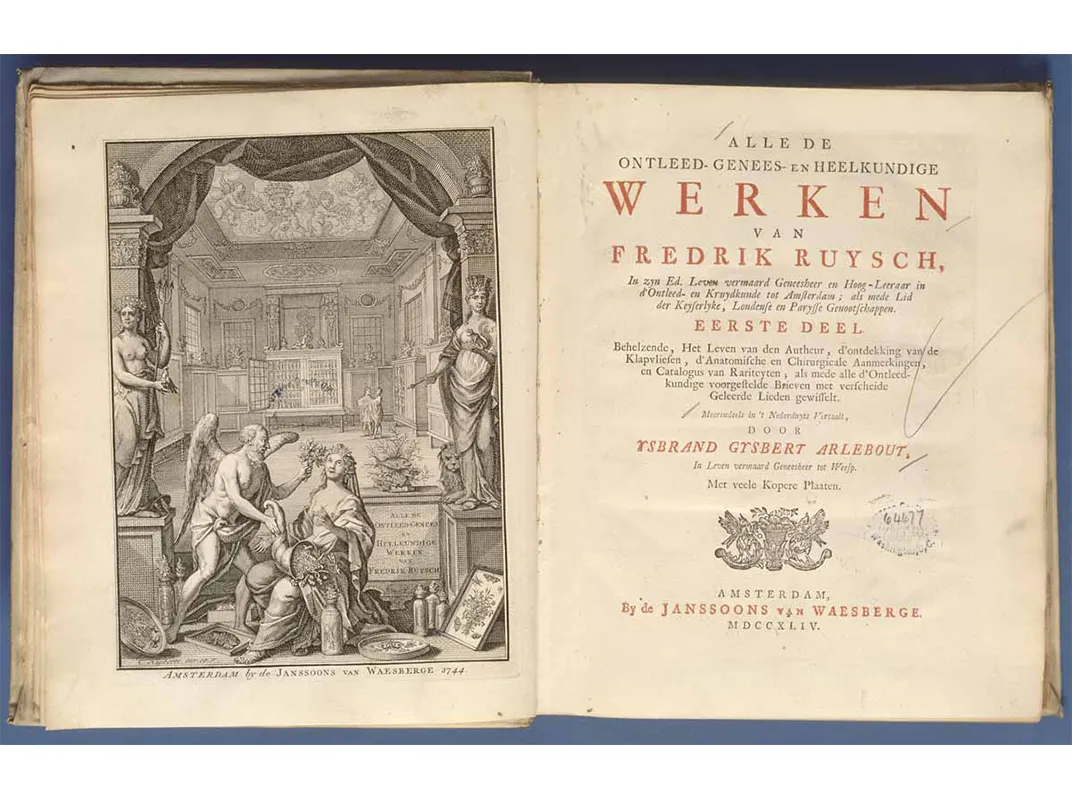

Frederik Ruysch, born on this day in 1638, was a doctor in Amsterdam in the late 1600s. And he made art out of people.

It’s not quite as weird as it sounds: in the active medical community of 1700s Amsterdam, physicians were taking an unprecedented interest in how the body worked internally, and it was a place where art and science intersected, like the famous anatomical drawings of Andreas Vesalius, which show bodies missing skin and sometimes other parts of their anatomy in active poses. Ruysch, who was a technological innovator when it came to preserving bodies for study, just took it a few steps further.

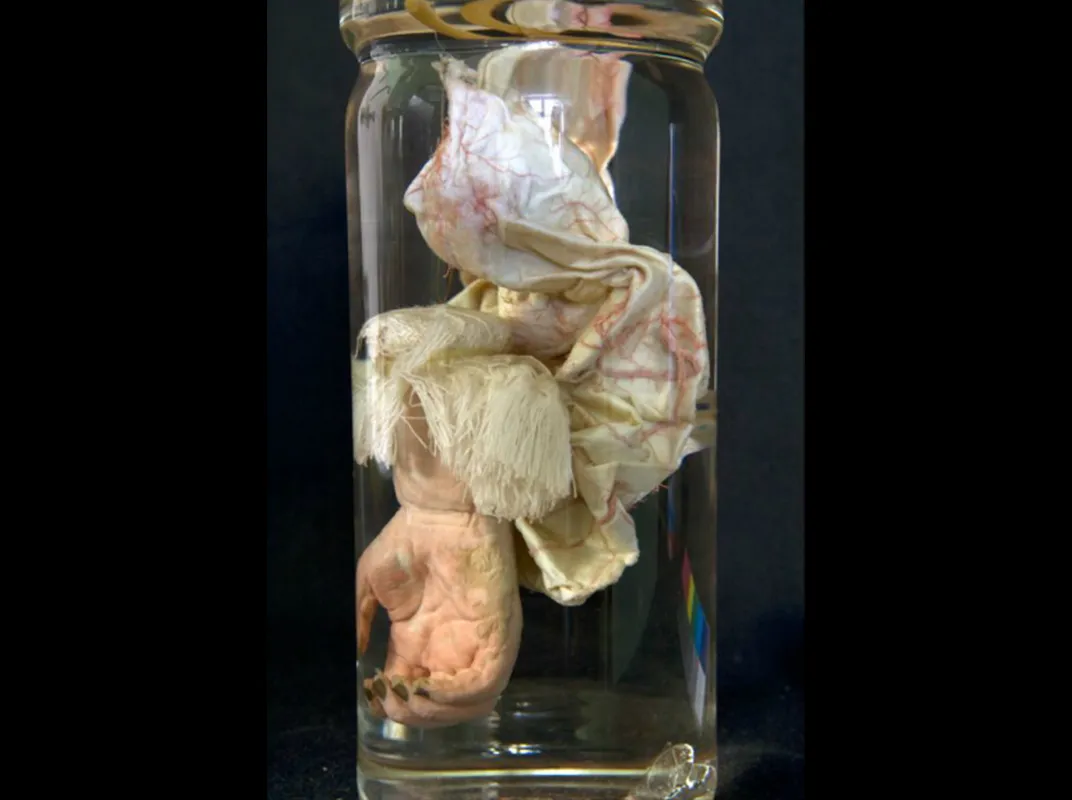

A few… weird steps. Some of his specimens were preserved in artful dioramas which also included plants and other materials, while other bodies were displayed clothed or decorated with lace. Ruysch was a leader in a new field, writes the National Library of Medicine.

Like other anatomical artists who followed, the library writes, Ruysch also used disconnected body parts as sculptural material. The pieces were preserved, and sometimes colored or put into clothing before they were arranged. What made Ruysch’s work stand out was the attention to detail.

As a prominent figure in the surgical community who also worked with midwives and babies, writes historian Julie Hansen, Ruysch also had plenty of access to the bodies of stillborn or deceased babies he used to create “extraordinary multi-specimen scenes,” she writes. Ruysch “was responsible for creating a new aesthetic of anatomical demonstration in Amsterdam.”

“In making such displays, he claimed an extraordinary privilege,” writes the library: “the right to collect and exhibit human material without the consent of the anatomized.”

Issues of consent aside, the ways that Ruysch posed his subjects are certainly morbid. But his work had a specific logic, writes historian Jozien Driessen van het Reve. By placing body parts in a familiar scene like a diorama, he intended to distance viewers from the fact that they were looking at a dead body.

“I do this to take away from these people all repulsion, the natural reaction of people confronted with corpses being one of fright,” he explained, according to historian Luuc Kooijmans. In pursuit of this goal, Ruysch developed new techniques of preserving body parts that pushed the field of anatomy forward.

Among his other innovations, writes Koojimans, Ruysch was a pioneer in the use of alcohol to preserve body parts for long periods of time. He also used cutting-edge techniques like wax injections to make organs and blood vessels look alive, rather than collapsing.

This meant that unlike anatomists of the period who had to dissect and catalogue quickly because the body they were working on would quickly decay, Ruysch was able to build up a collection of body parts. This collection grew so big that he opened a museum in the 1680s, writes Koojimans. The public could attend, viewing the specimens as morbid entertainment and paying an admission fee. But doctors could come in for free and attend lectures Ruysch gave on anatomy.

Surviving parts of Ruysch's collection, which comprised thousands of specimens at its height, were preserved by Russian curators over the centuries, and they remain in a Russian collection today. Although his work might seem strange today, consider Bodyworlds and other modern exhibits that use plastination to preserve slices of human cadavers for the entertainment (and edification?) of the general public.