Wolves and the Balance of Nature in the Rockies

After years as an endangered species, the wolves are thriving again in the West, but they’re also reigniting a fierce controversy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/a9/b0a955d5-f54b-4365-8706-fc4af7ee1c1d/feb09_d04.jpg)

Roger Lang looked at two black wolves looking back at him. "I knew they wouldn't get them all," he said, steadying his binoculars on the steering wheel of his pickup truck. "Some of them were trapped. Some were shot from helicopters. They culled nine and actually thought they got the whole pack. But you can see they didn't."

Sloping down to the Madison River, Lang's 18,000-acre Sun Ranch in southwest Montana is an Old West tableau of rippling prairie, plunging streams, ghostly bands of elk, browsing cattle—and, at the moment, two wolves poised like sentinels on a knoll beneath the snowy peaks of the Madison Range. About 25 miles west of Yellowstone National Park, the ranch straddles a river valley that is part of an ancient migration corridor for elk, deer, antelope and grizzly bears that move seasonally in and out of Yellowstone's high country.

Lang has a close-up view of one of the most dramatic and contentious wildlife experiments in a century—the reintroduction of wolves to the northern Rocky Mountains, where they were wiped out long ago. Caught in Canada and flown to Yellowstone, 41 wolves were released in the area between 1995 and 1997, restoring the only missing member of the park's native mammals. Since then, wolves have begun migrating in and out of the park, their howls music to ears of wilderness lovers and as chilling as war whoops to many ranchers.

Wolves from Yellowstone were on Lang's property by the time he acquired it in 1998. A former Silicon Valley entrepreneur who amassed a fortune in the software business, he seeks to breach a gap between people—including many transplanted urbanites—who would grant wolves unconditional amnesty and others who would exterminate them. "Wolves were here before we were and deserve a place," said Lang. "But that doesn't mean some of them aren't going to die if they misbehave."

After wolves killed five of his cows, he consulted with federal wildlife officials, who pass sentence on incorrigible wolves. "The feds proposed taking out the whole pack and we acquiesced," he said.

As he peered again at the two surviving wolves, Lang's half-smile conveyed a mixture of alarm and relief. "They are remarkable animals."

Revered and reviled, the wolf embodies society's conflicted relationship with nature. A bronze wolf guarded the shrine of Apollo at Delphi; a wolf stalks a child in Little Red Riding Hood. Plains Indians respected the wolf as a great hunter and as a guide to the spirit world; American settlers slaughtered more than a million wolves during the 1800s. Trappers killed wolves that raided their traplines and sold the pelts for a dollar apiece. Stockmen's associations offered bounties for dead wolves. The slaughter was abetted by an ancient antagonism. Even Teddy Roosevelt, the cowboy conservationist, called the wolf a "beast of waste and desolation" and hunted it mercilessly.

The federal government began subsidizing wolf extermination on federal lands in 1915, and the last known wolf den in Yellowstone—prior to the wolf's recent comeback—was destroyed in 1923. By the 1940s, the animals were extinct in the northern Rocky Mountains—shot, trapped or poisoned. (A few hundred remained in the United States, mostly in northern Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan.) Then, at the dawn of the modern conservation movement and "coinciding with the paving of America," says Thomas McNamee, author of the 1997 book The Return of the Wolf to Yellowstone, the wolf emerged as a symbol of the nation's vanishing wild heritage. It was among the first animals protected under the 1973 Endangered Species Act.

The idea of returning the gray wolf, Canis lupus (which can be gray, black or white), to Yellowstone goes back to the Nixon administration. Proponents have argued that the wolf was a keystone species whose presence would reinvigorate the natural order. Without it, they said, Yellowstone was incomplete, the West a bland facsimile of its old wild self. "We have a psychological need for something big and bad that represents wildness. Wolves fulfill that," said Jim Halfpenny, an ecologist and author who has been leading wildlife classes in the park for nearly 40 years. Western lawmakers resisted reintroduction at first but eventually agreed to the plan. A loophole in the wolves' endangered species status authorized U.S. wildlife officials to kill animals that preyed on livestock on federal land and permitted landowners to do the same on their property. The loophole did not apply to wolves in the park: they remained under the full protection of the Endangered Species Act, as did a small number of wolves that had begun moving on their own into northern Montana from Canada in the late 1970s.

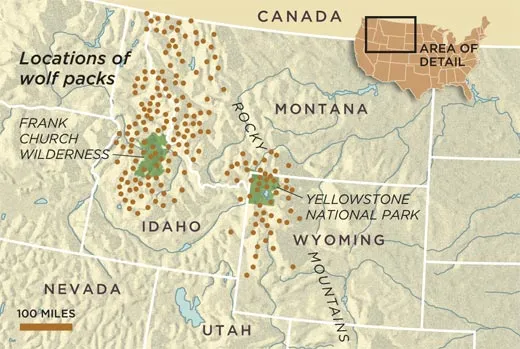

About the same time wolves were finally released in Yellowstone, three dozen others were also reintroduced in Idaho's Frank Church Wilderness. Both groups reclaimed old haunts with unanticipated gusto. Some of the park wolves scaled a ten-foot-high chain-link enclosure around their acclimation pen, and then dug under the fence to let out the rest of the wolves. Two traveled 40 miles within a week of gaining their freedom.

During the first decade after reintroduction, the wolf populations soared. By 2007, an estimated 1,500 wolves inhabited the northern Rockies of the United States—many descended from released wolves, others from the Canadian immigrant packs—with about 170 in Yellowstone.

To many naturalists, the thriving wolf population was a hopeful sign that it was possible to restock wild country with long-lost native inhabitants. But as the wolves made themselves at home again, old adversaries in the ranching community sought broader license to kill them.

By the end of 2007, wolves had been implicated in the deaths of about 2,700 livestock in Montana, Idaho and Wyoming in the dozen years since their reintroduction. They were preying on sheep and cattle at a rate higher than government scientists had predicted. Still, the predation represented a small fraction of all livestock losses.

One environmental group, Defenders of Wildlife, which has been a strong advocate of wolf reintroduction, established a fund to compensate ranchers for cows, sheep and other animals killed by wolves. The group reports it has paid ranchers about $1 million. The compensation doesn't make up for all the losses ranchers cite, such as the lower prices fetched for thin, wolf-harried cattle or the cost of extra manpower and material to protect livestock from predators.

By 2003, many Westerners were insisting that wolves be subject to more lethal control, which would require the animals' removal from the endangered species list. They got their way in early 2008, when the Bush administration ceded responsibility for most of the Rocky Mountain wolves to state officials in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. The states quickly adopted rules that sanctioned wolf hunts and generally made it easier to kill the animals. Wolves within Yellowstone's boundaries along with those in northern Montana remained under federal protection.

In the first month of relaxed regulation, at least 37 wolves were killed across the three states. By the end of July, more than 100 were dead. Bumper stickers proclaimed "Wolves—Government Sponsored Terrorists." Politicians stirred the pot. Idaho Gov. C.L. "Butch" Otter was widely quoted saying "I'm prepared to bid for the first ticket [hunting license] to shoot a wolf myself." Gov. Dave Freudenthal of Wyoming questioned whether any wolf packs outside Yellowstone in his state "are even necessary."

"I'm kind of a tree hugger myself and I've never killed a wolf," said Jack Turnell, whose family has run the Pitchfork Ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming, for most of the past century. "But the wolf people lied to me. They asked me would I resist having 100 wolves in Yellowstone. 'No,' I said, if I could stop them at the borders. Now, all of a sudden we have 1,500 wolves. One of 'em can kill 20 of something in a year. You need to say they can't get into farm and ranch areas. You can't turn wolves loose like they were a bunch of balloons."

Wolves have nipped hard at the pocketbooks of people like Martin Davis of Paradise Valley, Montana, who guides elk hunters in the mountains north of Yellowstone National Park. As the wolves have feasted on the herds, there have been fewer elk for hunters to shoot. "Our hunting has really gone lousy," Davis said. "Our repeat clients are saying when they see less wolves and more elk, they'll come back."

But the Yellowstone wolves have attracted a passionate following. Surveys conducted by the National Park Service found that nearly 100,000 people come to the park each year from other states specifically to see wolves. Visitors have formed attachments to individual wolves, and certain ones seem to have had a knack for playing to the crowd. A park favorite was a lame but bold male, nicknamed Limpy. He was shot and killed outside the park last spring.

The shooting of Limpy and other wolves spurred conservationists to challenge the new state management plans. They singled out Wyoming's especially permissive approach to killing wolves. "It's antithetical to good wildlife management. It just allows an animal to be killed for the sake of killing it," said Hank Fischer, of Missoula, Montana, who helped establish the fund to reimburse ranchers who lost livestock to wolves.

Twelve environmental groups sued to return management of the wolves to the federal government, arguing that the Yellowstone wolf population would not be sustainable until members mated with wolves in Idaho or northern Montana. By allowing hundreds of wolves to be killed outside the park, the lawsuit claimed, populations would be cut off from one another, and inbreeding would eventually weaken them, making them more vulnerable to disease, drought and other perils.

The court largely agreed. "The reduction in the wolf population that will occur as a result of public wolf hunts and [predator] control laws in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming is more than likely to eliminate any chance for genetic exchange to occur," U.S. District Court Judge Donald Molloy wrote in a ruling this past summer that effectively overturned the federal move to let the three states regulate wolf hunting. The ruling restored the wolf's status to what it was at reintroduction: only animals that take livestock may be killed.

Of all the people who supported easing the restrictions on wolf hunting, perhaps the most surprising was Douglas W. Smith, a biologist who heads the Yellowstone Wolf Recovery Project and is the co-author of the 2005 book Decade of the Wolf. He helped carry the first wolves into the park in crates 14 years ago and has functioned as their head nanny ever since. But he also has sympathy for his ranching neighbors. "We covet what we've lost, and when you go out and see wolves free in nature, it's real," he said. "Most people are so many levels removed from wild nature that seeing wolves establishes a very powerful link. But ranchers already have a strong connection. They don't need wolves for that."

Smith agrees that Yellowstone's wolves need to mix with animals outside the park to strengthen their genetic stock. It's just that he doesn't think hunting or stricter predator control laws will prevent that. "I have faith in the wolves," he said during an interview in his office at Yellowstone National Park headquarters. "They will find each other."

If they are allowed to, that is. Even if the wolves continue to roam relatively more freely, their future survival would not be guaranteed in a part of the country where human development is quickly expanding into wildlife habitat.

For now, the reintroduced wolves appear to be doing the job they were recruited to do—put more teeth in the natural order that had been out of whack since the wolves disappeared in the early 20th century. By 2005, they were killing around 3,000 elk every year in Yellowstone, where outsized herds had been denuding the park's vegetation. Much of the elk predation took place in the Lamar Valley in the northeast quarter of the park, a stretch of open space that has been compared to East Africa's Serengeti Plain. For all its magnificence, it has been something of an unbalanced ecosystem, the absence of trees due in no small part to an overabundance of browsing elk.

With wolves back on the prowl, the elk became more restive. And as the elk spent less time foraging along stream banks, scientists have reported that willows and other plants that had been eaten to the nubs began to flourish again. So did some of the animals that depend on the trees, like beavers, which use willow branches to build lodges. Since the wolves were reintroduced, beaver colonies have increased eightfold. So there are more beaver ponds—habitat for insects, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, even moose, Smith says. Especially in winter, wolf kills have provided food for other park dwellers, including ravens, magpies and bald and golden eagles.

For human visitors to the park, one of the highlights of wildlife viewing in recent years has been watching the combat between wolves and grizzly bears, alternately fierce and comical, for control of elk carcasses. Wolf watching generates more than $35 million a year for motels, restaurants and other businesses in the three states surrounding the park, according to park surveys.

Hard-core wolf watchers arrive at first light, their cars filling roadside turnouts in the Lamar Valley. They erect a picket line of spotting scopes and point their lenses at den sites in the hillsides that frame the valley. Some of the regulars act as volunteer aides to the wolf recovery project, documenting the appearance of new pups, changes in den sites and interactions with other animals.

"Getting to know a wolf pack is like getting to know a family," said Laurie Lyman. Three years ago, she and her husband retired from teaching jobs in San Diego and moved to Silver Gate, Montana, just outside the park's northeast entrance and a 30-minute drive from the Lamar Valley. "Each wolf has its own individual temperament—the ones that nurture the pups, the males that feed the females. Everybody means something in the pack. Each wolf contributes. One of my goals is to get more people to look into the lives of wolves so they better understand the effect they have when they kill wolves."

A wolf pack has a familial makeup, typically consisting of parents and one or more generations of offspring. Slow to mature sexually, wolf pups stay with their parents up to four years, longer than many other mammals. In the process, the pups learn about hunting, foraging and working with other members of the pack.

The number of wolves in a pack varies with the size of their prey. Wolves that dine regularly on big animals—bison, elk or caribou—tend to operate in large packs of up to 15 members. In summer, packs are likely to split up, with individuals traveling 20 or more miles a day in pursuit of small prey such as squirrels and beaver. In winter, when snow slows down bigger animals, a wolf pack tends to work together, bringing down an elk every other day or so.

The constant combat takes a toll. In Yellowstone National Park, where only 2 percent of mortality is caused by humans—mostly by car accidents— the average life span of a wolf is still only four to five years. (Wolves in captivity sometimes live into their teens.) When he examines wolves that have died in the park, Smith routinely finds smashed bones, teeth ground to useless stubs and scars from fights with rival packs, moose and bison. Disease has also exacted a heavy price. Two-thirds of the pups born in 2005 died from distemper, a viral infection that strikes the respiratory and central nervous systems.

Diminishing food sources alone are likely to limit the growth of the Yellowstone wolf population. Smith predicts that it will eventually stabilize at around 100 animals, about 40 percent smaller than its 2007 size. Today, half of Yellowstone's wolves live in and around the Lamar Valley, where the animals were first reintroduced. Recently, said Smith, wolves have begun killing each other in fights over elk carcasses, a sure sign that prey is getting scarcer. "We've not seen anything like that level of wolf on wolf mortality before."

Yellowstone may be the nation's best-known wildlife haven, but it's not a stable environment. Today, park ecologists are alarmed about the spread of nonnative plants, which have more than doubled in the past 20 years, possibly because of warming temperatures and a longer growing season. Some of the exotics, such as cheat grass and alyssum, a mustard, are shunned by wildlife and may crowd out natural vegetation that feed the elk, deer and bison that are staples of the wolves' diet.

Outside the two-million-acre park, the landscape is also changing. Since 1970 the amount of open space around the park that has been used for new homes has grown by 350 percent, while the human population has increased by more than 60 percent.

For Yellowstone's wolves to continue thriving, Smith said, the animals will need access to corridors of open country that allow them to move west and north and ultimately breed with counterparts in Idaho and northern Montana. "If there's any animal that can move the necessary distance, it's a wolf, if we give them any sort of opportunity," he said.

One crucial corridor from Yellowstone to Idaho's Frank Church Wilderness, where reintroduced wolves continue to do well, follows creeks that run through Roger Lang's ranch in the Madison Valley and water meadows where his cattle graze. Today, the scattered signs of modern civilization in the valley are still dwarfed by the great green sweep of untrammeled countryside. But the beauty of the place can work against it. According to Lang, one-third of the valley is being developed, a third is protected and the rest is up for grabs.

This past fall, Lang established a conservation easement on the majority of his property. "Our intent is to preserve a wild corridor through this valley," Lang said.

Lang has worked hard to coexist with wolves that have taken up residence on his ranch. He has used firecrackers and rubber bullets to keep wolves away from his cows. He has employed night riders to patrol fence lines. This past year he strung miles of fluttering pennants from wire fences. The practice, known as fladry, has been used by stockmen in Europe and Canada to deter wolves.

A few days after ranch hands attached Lang's flags, he found fresh wolf tracks directly underneath them.

Lang acknowledges that his ability to absorb some financial losses makes him more tolerant of wolves than some of his neighbors. At the same time, his willingness to kill problem wolves on occasion has antagonized local environmentalists. "The purpose is to find a balance," Lang said. "Preservation of the species is not the same as protecting every member."

Removed from the scientific challenges of working in Silicon Valley, he still thinks of himself as a problem solver. "Wolves have to be part of the equation. The trick is how to create a détente with them. We're just asking for everyone to be patient while we experiment with ways to make it happen."

Frank Clifford is the author of The Backbone of the World: A Portrait of the Vanishing West Along the Continental Divide.