Why We Should Rethink How We Talk About “Alien” Species

In a trend that echoes the U.S.-Mexico border debate, some say that calling non-native animals “foreigners” and “invaders” only worsens the problem

:focal(2211x1028:2212x1029)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/56/34560634-8a80-496e-ae1c-fd0b735efc8f/ajytgk.jpg)

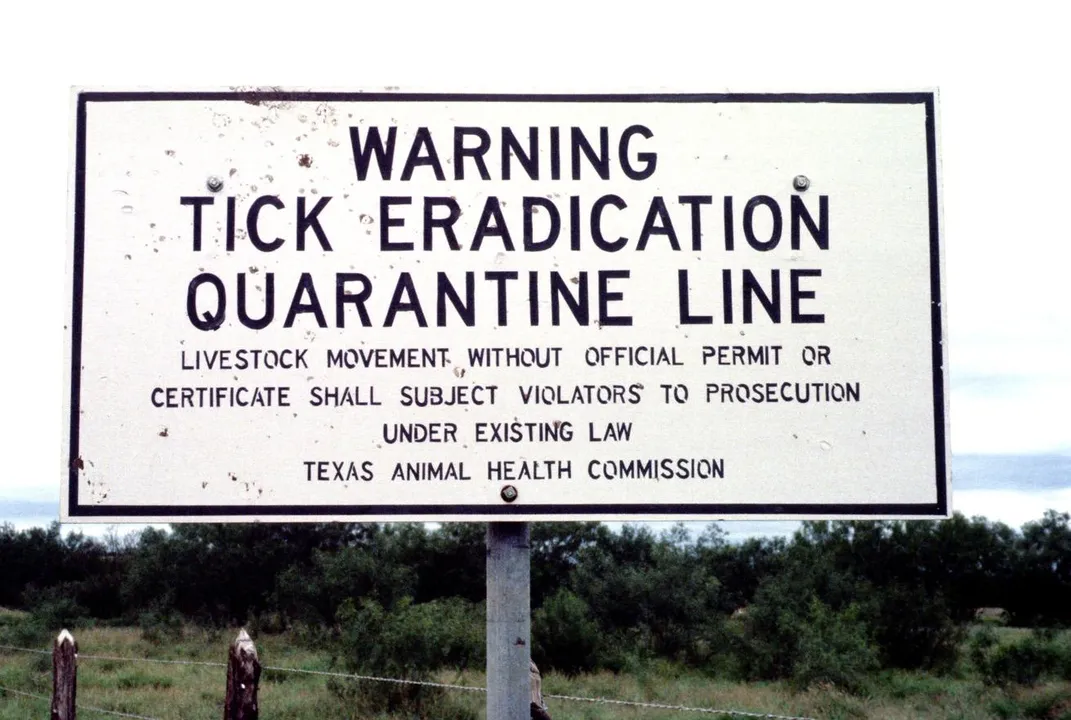

In South Texas, government agents patrol a barrier line that snakes some 500 miles along the course of the Rio Grande. Their mission: to protect their country from would-be invaders. But these aren’t the U.S. Border Patrol—they’re employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And their purpose is to keep out the ticks that carry cattle fever, a deadly bovine disease endemic to Mexico.

The USDA's “tick riders,” as they are called, are tasked with keeping infected cattle from straying deeper into Texas, where the deadly fever poses a serious threat to the beef industry. Whenever they find a stray or infected cow, they track it down and dip it in pesticide to kill the ticks and prevent them from spreading. Yet despite their best efforts, the tick riders' challenge has recently increased, as more and more of the hardy ticks find their way across the border.

A large part of the problem is that cattle fever ticks also have another host: Nilgai antelope, a species native to India that was imported to North America in the 1930s as an exotic target for game hunters. These antelope, like the ticks themselves, and the pathogen they carry, are considered an invasive species. They are cursed not only for their role as a disease vector, but because they eat native plants and compete with cattle for food.

That’s why, unlike native white-tailed deer—which also host ticks—they are subject to an unrestricted hunting season, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sponsors regular Nilgai hunts in protected areas.

The differences in how authorities treat domesticated cattle, native deer and wild, imported antelope illustrate a stark divide in ecology. For decades, both scientists and laypeople have referred to organisms like the Nilgai as “alien,” “exotic” and “invasive.” But as long as ecologists have warned about the danger of invasive species, others have asked whether this kind of language—which carries connotations of war and xenophobia—could cloud the science and make rational discussion more difficult.

In the same border region, U.S. immigration officers patrol their own line, looking for signs of illegal human immigration into the United States. If caught, these immigrants—often referred to as "aliens” by the media or even “illegals” by the president—face arrest and deportation. The parallel has not been lost on those who study invasive species. In a recent essay, New School environmental studies professor Rafi Youatt wrote that a trip to Texas left him contemplating “the opposition of invasiveness to nativeness and purity” and “the many ways that invasiveness attaches to both human and nonhuman life.”

In an era of renewed focus on borders, it’s hard to ignore the similarities between how we talk about non-native animals—hyper-fertile “foreigners” colonizing “native” ecosystems—and the words some use to discuss human immigration. And as international relations have become more heated, so too has the debate among researchers over the pointed rhetoric we use to talk about animals, plants and micro-organisms that hail from elsewhere.

...

Charles Darwin was perhaps the first to posit the idea that introduced species might outcompete natives. In 1859, he wrote that “natural selection … adapts the inhabitants of each country only in relation to the degree of perfection of their associates,” so organisms that evolved under more difficult conditions have “consequently been advanced through natural selection and competition to a higher stage of perfection or dominating power.” It would be another 125 years before invasion ecology coalesced as a subfield. But by the 1990s, it was driving public policy.

Today, governments and non-profits dedicate considerable resources to controlling invasive species. The U.S. and Canada spend tens of millions of dollars a year to keep Asian carp out of the Great Lakes. Eurasian garlic mustard is a common target of volunteer weed-pulls organized by local parks departments. Estimates of the number of invasive species vary widely: according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, there may be as many as 50,000 non-native species in the United States, including 4,300 that could be considered invasive.

The devastation wrought by these plants, animals and microbes has inspired both desperate and creative measures—from government-sponsored eradication of non-natives off entire islands to restaurants that put invasive species on a plate. These efforts are motivated by very real concerns about economics, the environment and human and animal health. But the idea that non-native species are inherently undesirable also has a dark history.

In the 19th century, European and American landscape architects expressed a patriotic pride that was sometimes tinged with nativist suspicion of “foreign” plants. In the 1930s, the Nazis took this concept to the extreme with a campaign to “cleanse the German landscape of unharmonious foreign substance.” One target was an unassuming Eurasian flower, Impatiens parviflora, which a 1942 report condemned as a “Mongolian invader,” declaring, “[A]n essential element of this culture, namely the beauty of our home forest, is at stake.”

Today’s critics of invasive species rhetoric are quick to clarify that they aren't calling their colleagues racist. But Macalester College ecologist Mark Davis, for one, questions whether our modern campaign against non-native species has gone too far.

Davis is perhaps the field’s most notorious heretic, lead author of a widely-read 2011 essay in the journal Nature, co-signed by 18 other ecologists, that argued for judging non-native species based on environmental impact rather than origin. He believes that invasion ecology has been led astray by its central metaphor: the idea that non-native species are invading native ecosystems, and that we are at war with them.

“Militaristic language is just so unscientific and emotional,” says Davis. “It’s an effective way to bring in support, but it’s not a scientific way.”

…

The idea of invaders from elsewhere, whether human, animal or vegetal, taps into one of the bedrocks of human psychology. We form our social identity around membership in certain groups; group cohesion often relies on having a common enemy. Fear of contamination also drives human behavior, an impulse frequently evident in rhetoric about so-called “illegal immigrants” whom President Trump has declared—erroneously—to be bringing “tremendous infectious disease” across the border.

Davis does not dispute that many non-native species are harmful. Novel viruses like Zika and Ebola clearly threaten human health. Long-isolated animals on islands or in lakes have been quickly wiped out after new predators arrived along with humans. But he argues that most introduced species are harmless, and some are even beneficial. The U.S. government has spent 70 years trying to eradicate tamarisk shrubs from the Southwest, for example, but it turns out the plants are now a preferred nesting spot for an endangered songbird.

Inflammatory rhetoric may be counterproductive, encouraging us to expend resources fighting problems that are not really problems, says Davis. “The starting point should not be that these are dangerous species,” he says. “You need to focus on what they do. We’re taught, don’t judge people because of where they come from—it should be the same with novel species.”

Many of Davis’s colleagues argue the opposite: that it’s dangerous to assume non-native species are innocent until proven guilty. Numerous examples from history back them up: In 1935, farmers carried two suitcases of South American cane toads to Australia, hoping they would eat the beetles that plagued their sugar cane crop; today, more than 1.5 billion of the toxic amphibians have spread across the continent, poisoning native animals who try to eat them. Brown tree snakes, inadvertently imported to Guam after World War II, wiped out all the island’s native birds.

Daniel Simberloff, a respected ecologist at the University of Tennessee, is one of Davis’s colleagues who disagrees with his approach. In fact, he compares Davis and others who share his views to people who—despite overwhelming scientific consensus—deny the existence of climate change. “So far it hasn’t been as dangerous as climate denial,” Simberloff says, “but I’m waiting for this to be used as an excuse not to spend money [on controlling invasive species.]”

Simberloff is the author of the 2013 book Invasive Species: What Everyone Needs to Know, a book aimed at policy-makers, land managers and others who are working to fight the spread of invasive species. He recoils at the idea that the work of modern invasion biology, and the language scientists use to talk about it, has any relation to xenophobia against humans. Military language, he says, is often simply an accurate description of the threat and the necessary work of mitigating it.

“If we’re allowed to say ‘war on cancer,’ we should be allowed to say ‘war on cheatgrass,’” he says, referring to the prolific Eurasian weed that has fueled increasingly intense wildfires throughout the Western United States. “Does it help generate policy and higher-level activities that would not otherwise have been? Maybe. Legislators are not scientists and are probably motivated by colorful language—‘They’ve made a beachhead here,’ ‘We’ve got to put out this fire,’ or what have you.”

…

Still, Simberloff has noted a gradual shift in vocabulary among his colleagues over the past decade, which he reasons has to do with greater awareness of the political implications of certain words—especially words we also use to talk about people. Today, for example, few American scientists use the word “alien” to refer to these species, despite its continued appearance in books and articles directed at a general audience.

“It has a pejorative connotation now in the U.S.,” Simberloff explains. “People tend to say ‘non-indigenous’ or ‘non-native’ now.”

Outside of academia, there is also evidence that conservation workers who confront invasive species directly are moving away from military metaphors. In a recent paper for the journal Biological Invasions, researchers at the University of Rhode Island interviewed New England land managers working on coastal marshes and found that they no longer spoke of the now-common invasive reed Phragmites australis in militaristic terms.

Instead of “trying to battle with, kill, eradicate, or wage war upon Phragmites in coastal ecosystems,” the managers tended to discuss the reed in the context of ecosystem resilience. They even went so far as to note the ability of Phragmites to build up elevation as sea levels rise, perhaps mitigating the impact of climate change on vulnerable marshland.

These shifts in metaphor and terminology are necessary, says Sara Kuebbing, a post doc in ecology at Yale who was a student of Simberloff’s.

“Terms like ‘alien’ and ‘exotic’ have a lot of baggage,” she says. “We’re such a young field, and in the beginning everyone used their own terms to describe non-native species, but I don’t think they were thinking very deeply about the social implications of these words. Consolidating around consistent terminology is really important for the field, and for us to communicate to others, to help people understand the difference between non-native and non-native invasive species as we translate science into policy and management.”

…

A shift in rhetoric isn’t the only way that international border disputes impact ecology. Today, human-made borders interrupt natural environments, making it harder to control invasive species and protect ecosystems.

The challenge is more than physical. The United States and Canada depend on one another to keep Asian carp from reaching the Great Lakes, for example. And while U.S. border agencies like the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service make numerous references to their role as “our first line of defense” against “alien species,” scientists say that this sort of fortification can only hold so long without communication and cooperation between neighboring countries, trade partners, indigenous groups and local communities.

On the tick line in South Texas, the resurgence of cattle fever and the looming threat of vector-borne pathogens spreading with climate change has made the importance of cross-border cooperation especially clear. While there is no vaccine in the United States, Mexico does have one. The problem? It’s made in Cuba, and despite research showing its effectiveness against one of the two cattle tick species, sensitive international politics have delayed its approval for widespread use north of the border.

The prospect of a vaccine is “exciting,” says Pete Teel, an entomologist at Texas A&M. Meanwhile, however, violent drug cartels in Mexico represent a new complication, as they threaten to make wildlife control and quarantine enforcement more dangerous. While scientists in both countries are eager to work together, the darker side of human nature—our violence, greed and fear of the foreign—is always poised to interfere.

“Despite whatever is going on elsewhere, people are working to manage this, and ideas move back and forth between Texas and Mexico,” Teel says. “But everything is intertwined across the border.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)