What Is the Most Annoying Sound in the World?

A new study examines the neurological basis for unpleasant noises—and finds exactly which sounds are the most irritating

![]()

A new study examines which sounds are most unpleasant to the human ear. Image via Flickr/Stephen Dann

It’s so universal that it’s become a cliché: nails on a chalkboard. When it comes to noises that bother everyone’s ears, it’s seemingly a given that scraping fingernails across a slate board is the one that everyone hates most.

But when a group of neuroscientists decided to test which sounds most upset the human brain, they discovered that fingernails on a chalkboard isn’t number one. It’s not even number two. As part of their research, published last week in the Journal of Neuroscience, they put 16 participants in an MRI machine, played them a range of 74 different sounds and asked them to rate which were most annoying. Their top ten most irritating sounds, with links to audio files for the worst five (although we can’t imagine why you’d want to listen):

1. A knife on a bottle

2. A fork on a glass

3. Chalk on a blackboard

4. A ruler on a bottle

5. Nails on a blackboard

6. A female scream

7. An anglegrinder (a power tool)

8. Squealing brakes on a bicycle

9. A baby crying

10. An electric drill

They also played the participants a number of more pleasant noises. Here were the four they rated as the least irritating:

1. Applause

2. A baby laughing

3. Thunder

4. Water flowing

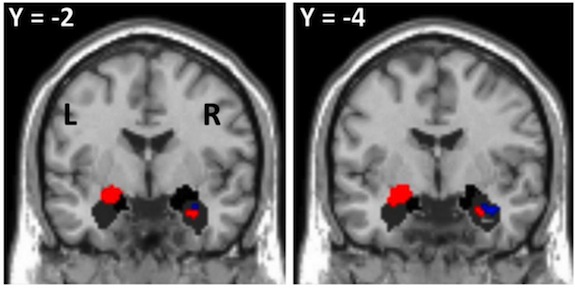

Even more interesting than the rankings were the parts of the brain that lit up with activity when the research participants heard the irritating noises. The MRI scans revealed that along with the auditory cortex (which processes sounds), activity in the amygdala—the region of the brain responsible for producing emotions—increased in direct proportion to the perceived unpleasantness of the sound. The researchers found that the amygdala interacted with signals coming from the auditory cortex, increasing the amount of unpleasantness conveyed by sounds at the top of the list, which all happen to occur in the frequency range between 2,000 and 5,000 Hz.

Brain activity in the amygdala increased for unpleasant sounds. Image via the Journal of Neuroscience

Why would the amygdala activate specifically for sounds within this range? “It appears there is something very primitive kicking in,” says Sukhbinder Kumar, the paper’s lead author, from Newcastle University in England. “Although there’s still much debate as to why our ears are most sensitive in this range, it does include sounds of screams which we find intrinsically unpleasant.”

Previously, scientists have speculated that we might found these sorts of high-pitched sounds so irritating because they acoustically resemble the alarm calls of our primate relatives, such as chimpanzees. At some point in our evolutionary history, the theory goes, we evolved the innate tendency to find these alarm calls emotionally terrifying so that we would be more likely to act upon them and avoid predators. Theoretically, this tendency might have stuck, despite the fact that fingernails scratching on a chalkboard have nothing to do with actual predators.

More recent research, though, makes this theory seem a bit less likely. In one experiment with cottontop tamarins, researchers found that the animals’ reactions to both high-pitched scraping noises (like nails on a chalkboard) and plain white noise were similar, whereas humans obviously find the former much more unpleasant.

An entirely separate hypothesis is much simpler: that the actual shape of the human ear happens to amplify certain frequencies to a degree that they trigger physical pain. If that’s the case, the repeated sensation of pain associated with these noises may lead out minds to automatically consider them to be unpleasant.

Researchers in the field of psychoacoustics continue to look into just which sounds we find most unpleasant and the reasons why we find some noises innately irritating in the first place. This writer, for one, eagerly awaits new findings—and wouldn’t mind not hearing much of it in the meantime.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)