In This Community of Brazilian Cave Insects, Females Wear the Penises, Literally

A genus of insect that inhabits caves in eastern Brazil has reversed sex organs, say scientists

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/29/1829b895-169f-4a0d-a199-ac23622456b5/neotrogla_copulationcropped.jpg)

In the caves of eastern Brazil, there lives a group of winged insects that mate in a way that will blow your mind.

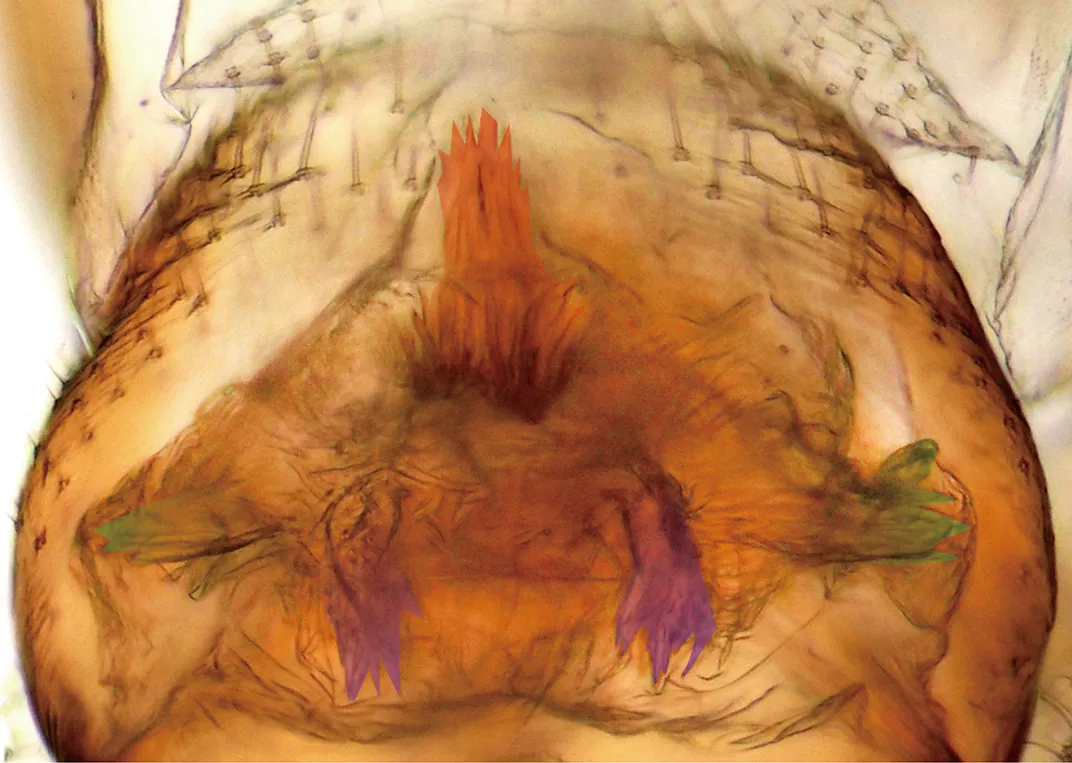

Mounting the male, Females of the Neotrogla genus penetrate males with a penis-like organ, in a standard lock and key situation. Tiny spikes secure the female penis to the male, and she slurps up the male’s sperm via the penis-like organ.

It’s weird – even for the natural world, which is filled with animals doing weird sex stuff. But, this is perhaps the first example of reversed sex organs in any animal. An international team of scientists describes this reproductive behavior in a study published today in Current Biology.

Nearly two decades ago, Rodrigo Ferreira, a cave ecologist the Federal University of Lavras in Brazil, discovered the insects on a caving expedition, but the young age of the specimen made identification impossible. Recently, scientists who work in Ferreira’s lab stumbled upon another insect specimen, so they began investigating, looping in taxonomist Charles Lienhard at Switzerland’s Natural History Museum of Geneva.

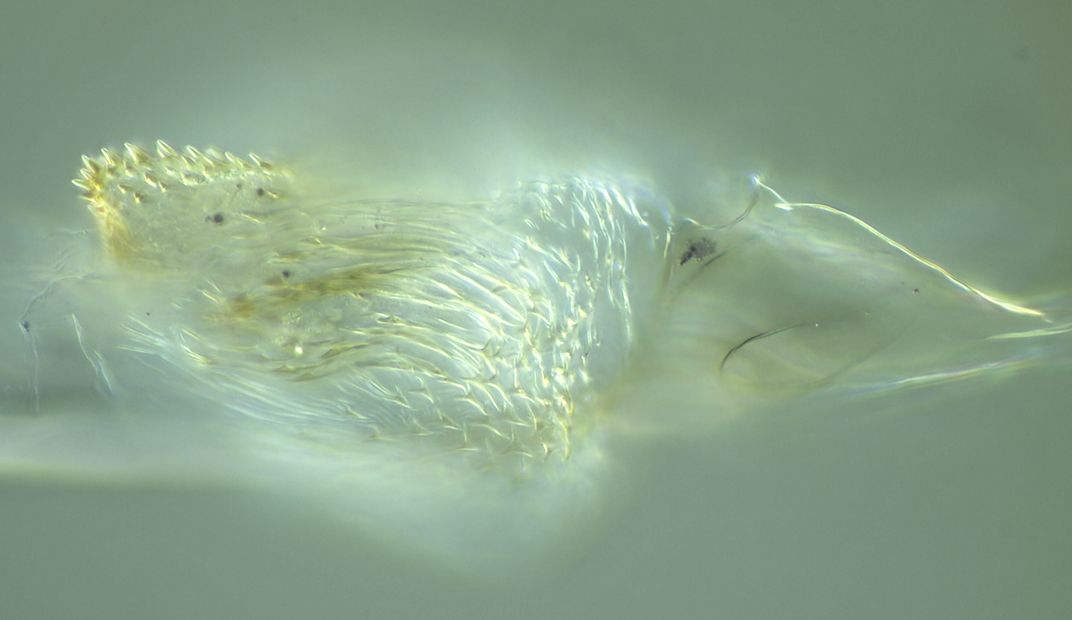

Upon dissecting the organisms, the researchers realized that females had an internal penis-like structure (that they likely only extended during mating) and the males had a pouch-like vagina. Nothing in the larger family of cave insects bore resemblance, and they realized they were looking at an entirely new genus with reversed sex organs. Altogether, they’ve found four separate species in this genus, called Neotrogla.

“The most impressive thing about the female penis is its complex morphology,” says Ferreira. From dissections the team figured out that each female penis-like structure is species specific, the penis spines or bristles from a specific species correspond to tiny pockets in the pouch of her male counterpart.

But, slicing open a bug to look at its sex organs is different than seeing how those sex organs work. The researchers also observed pairs of insects from one species (N. curvata) doing the deed in the lab. The insects also spent a lot of time mating – between 40 and 70 hours. That’s a lot of time to spend on sex, especially because sex leaves the insects open to predation.

During mating, the female’s spiny penis gets tightly anchored to the male vagina’s sperm duct, allowing the female to receive the semen. In other words, this penis functions more like a straw than a spout. If the male tried to break away, his abdomen would rip open, and he would dramatically lose his genitals. These female insects also mate with multiple males and can store two batches of sperm in the body.

Scientists believe that the penis generally evolved due to competition among males for fertile females, and a lot of evolutionary constraints would have to fall into place for such a dramatic reversal. “It requires harmonious evolutions of male and female genitalia and their exact match,” says Kazunori Yoshizawa, an entomologist at Hokkaido University in Japan and a co-author on the study.

So, what evolutionary constraints could drive this gender-bending scenario? Scientists have a hunch that the sperm comes with nutritional value because the female cave insects end up storing and then consuming the semen before producing eggs.

Cave environments are dark, dry, and low on food -- for the insects this is bat poop and dead bats. “Food scarcity seems to be very important in determining which species are able to colonize these environments,” says Ferreira. “The female penis, in this context, is certainly a good tool for getting a nutritious resource from males.” Thus, the male sperm would constitute a “nuptial gift” in scientific terms.

And there’s precedent for such nuptial gifts: Male katydids (Poecilimon sp.) transmit food with their sperm, and females compete for nutritious sperm – they even have a special elbow appendage to push opposing females out of the way. The cave insects may be living under similar evolutionary pressures, but confirming those suspicions demands further study.

This is hardly the first spiny penis in the biological world: male bean weevil beetles, dung flies, marmosets, some pythons, and domesticated cats all have spined penises. Some of these organs stimulate the female; while others might serve to violently pin the female down.

What truly sets the Neotrogla females apart is that they have a spiny penis-like organ, and it locks that male in place. That’s a total role reversal in sexual conflict. The female cave fly’s penis “underscores this range of variation in what it means to be male and female in the animal kingdom,” says Marlene Zuk, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul who was not associated with the study.

Female penis-like organs appear in other species, but none quite like this one: a female from an ancient mite species preserved in amber has a tube like organ that scientists think may have been used to grasp the male during sex; female seahorses transfer eggs to the males via a tube-like organ called an ovipositor, and the males ultimately give birth; and finally, female hyenas copulate, pee, and give birth through an elongated clitoris called a pseudo penis.

“Obviously more research is needed, but the whole thing is completely wild,” says Zuk.

“People tend to have this 1950s situation comedy view of sex in the animal world,” Zuk explained, but, “there are lots and lots of ways that selection on the sexes manifests itself – from dominant males to dominant females to, in this case, reversed genitalia.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)