The Giant Squid: Dragon of the Deep

After over 150 years since it was first sighted by the HMS Daedalus, the mysterious creature still eludes scientists

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/giant-squid-attacking-ship-631.jpg)

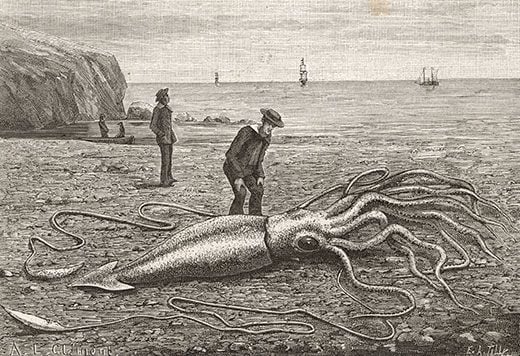

There are few monsters left in the world. As our species has explored and settled the planet, the far-flung areas marked “Here Be Dragons” have been charted, and toothy terrors once thought to populate the globe have turned out to be imaginary or merely unfamiliar animals. Yet some elusive creatures have retained their monstrous reputation. Foremost among them is Architeuthis dux—the giant squid.

The creature—likely the inspiration for the legendary kraken—has been said to have terrorized sailors since antiquity, but its existence has been widely accepted for only about 150 years. Before that, giant squid were identified as sea monsters or viewed as a fanciful part of maritime lore, as in the case of a strange encounter shortly before scientists realized just what was swimming through the ocean deep.

At about 5:00 in the afternoon on August 6, 1848, Capt. Peter M’Quhae was guiding the HMS Daedalus through the waters between the Cape of Good Hope and the island of St. Helena off the African coast when the crew spotted what they described as a gigantic sea serpent. The beast was unlike anything the sailors had seen before. News of the encounter hit the British newspaper The Times two months later, telling of the ship’s brush with a nearly 100-foot monster that possessed a maw “full of large jagged teeth … sufficiently capacious to admit of a tall man standing upright between them.”

M’Quhae, who was asked by the Admiralty to confirm or deny this sensational rumor, replied that the stories were true, and his account was printed a few days later in the same newspaper. Dark on top with a light underbelly, the sinuous, 60-foot creature had slipped by within 100 yards of the boat, and M’Quhae proffered a sketch of the animal made shortly after the sighting.

Precisely what the sailors had actually seen, though, was up for debate. It seemed that almost everyone had an opinion. A letter to The Times signed “F.G.S.” proposed that the animal was a dead ringer for an extinct, long-necked marine reptile called a plesiosaur, fossils of which had been discovered in England just a few decades before by fossil hunter Mary Anning. Other writers to the newspapers suggested the animal might be a full-grown gulper eel or even an adult boa constrictor snake that had taken to the sea.

The notoriously cantankerous anatomist Richard Owen said he knew his answer would “be anything but acceptable to those who prefer the excitement of the imagination to the satisfaction of judgment.” He believed that the sailors had seen nothing more than a very large seal and conferred his doubts that anything worthy of the title “great sea serpent” actually existed. It was more likely “that men should have been deceived by a cursory view of a partly submerged and rapidly moving animal, which might only be strange to themselves.”

M’Quhae objected to Owen’s condescending reply. “I deny the existence of excitement, or the possibility of optical illusion,” he shot back, affirming that the creature was not a seal or any other readily recognizable animal.

As was the case for other sea monster sightings and descriptions going back to Homer’s characterization of the many-tentacled monster Scylla in The Odyssey, attaching M’Quhae’s description to a real animal was an impossible task. Yet a series of subsequent events would raise the possibility that M’Quhae and others had truly been visited by overly large calamari.

The naturalist credited with giving the giant squid its scientific start was Japetus Steenstrup, a Danish zoologist at the University of Copenhagen. By the mid-19th century, people were familiar with various sorts of small squid, such as species of the small and widespread genus Loligo that are often eaten as seafood, and the basics of squid anatomy were well known. Like octopus, squid have eight arms, but they are also equipped with two long feeding tentacles that can be shot out to grasp prey. The head portion of the squid pokes out of a conical, rubbery structure called the mantle, which encloses the internal organs. Inside this squishy anatomy, the squid has two hard parts: a tough internal “pen” that acts as a site for muscle attachment, and a stiff beak that is set in the middle of the squid’s ring of sucker-tipped arms and used to slice prey. Since naturalists were only just beginning to study life in the deep sea, relatively few of the approximately 300 squid species now known had been discovered.

In 1857, Steenstrup combined 17th century reports of sea monsters, tales of many-tentacled giant creatures washed up on European beaches, and one very large squid beak to establish the reality of the giant squid. He called the animal Architeuthis dux. His only physical evidence was the beak, collected from the remains of a stranded specimen that had recently washed ashore. Steenstrup concluded: “From all evidences the stranded animal must thus belong not only to the large, but to the really gigantic cephalopods, whose existence has on the whole been doubted.”

Subsequent run-ins would leave no doubt as to the giant squid’s reality. In November 1861, the French warship Alecton was sailing in the vicinity of the Canary Islands in the eastern Atlantic when the crew came upon a dying giant squid floating at the surface. Eager to acquire the strange animal, but nervous about what it might do if they came too close, the sailors repeatedly fired at the squid until they were sure it was dead. They then tried to haul it aboard, unintentionally separating the tentacled head from the rubbery tail sheath. They wound up with only the back half of the squid, but it was still large enough to know that this animal was far larger than the familiar little Loligo. The ensuing report to the French Academy of Sciences showed that the poulpe could grow to enormous size.

Encounters in North American waters added to the body of evidence. A dead giant squid was discovered off the Grand Banks by sailors aboard the B.D. Haskins in 1871, and another squid washed up in Fortune Bay, Newfoundland.

The naturalist Henry Lee suggested in his 1883 book Sea Monsters Unmasked that many sea monsters —including the one seen by the crew of the Daedalus—were actually giant squid. (Accounts of M’Quhae’s monster are consistent with a giant squid floating at the surface with its eyes and tentacles obscured underneath the water.) The numerous misidentifications were simply attributable to the fact that no one actually knew such creatures existed!

Instead of being tamed through scientific description, though, the giant squid seemed more formidable than ever. It was cast as the villain in Jules Verne’s 1869 novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and in 1873 news spread of a giant squid that had allegedly attacked fishermen in Conception Bay, Newfoundland. The details are a little murky due to some creative retelling over the years, but the basic story is that two or three fishermen came upon an unidentified mass in the water. When they tried to gaff it, they discovered that the thing was a giant squid—which then tried to sink their boat. Some quick hatchet work sent the monster jetting away in a cloud of dark ink, and the proof of their encounter was a 19-foot-long tentacle. The fishermen gave it to the Rev. Moses Harvey, who was given the body of another giant squid by a different group of Newfoundland fishermen soon afterward. He photographed the latter specimen before sending it on to naturalists in New Haven, Connecticut, for study. The fame and reputation of the “devil fish” was at its acme—so much so that the showman P.T. Barnum wrote to Harvey requesting a pair of giant squid of his own. His order was never filled.

The giant squid was transformed into a real monster, and one whose unknown nature continues to frighten us. Not long after giving sharks a bad rap with Jaws, Peter Benchley made a particularly voracious giant squid the villain of his 1991 novel Beast. The second Pirates of the Caribbean film in 2006 transformed the squid into the gargantuan, ship-crunching kraken.

The enormous cephalopod still seems mysterious. Architeuthis inhabit the dark recesses of the ocean, and scientists are not even sure how many species are in the giant squid genus. Most of what we know comes from the unfortunate squid that have been stranded at the surface or hauled up in fishing nets, or from collections of beaks found in the stomachs of their primary predator, the sperm whale.

Slowly, though, squid experts are piecing together the natural history of Architeuthis. The long-lived apex predators prey mainly on deep-sea fish. Like other ocean hunters, they accumulate high concentrations of toxins in their tissues, especially those squid that live in more polluted areas. Marine biologists say that giant squid therefore can act as an indicator of deep-sea pollution. Giant squid strandings off Newfoundland are tied to sharp rises in temperature in the deep sea, so giant squid may similarly act as indicators of how human-driven climate change is altering ocean environments. There are two giant squid, measuring 36- and 20-feet long, on display in the National Museum of Natural History’s Sant Ocean Hall. As NMNH squid expert Clyde Roper points out, they are “the largest invertebrate ever to have lived on the face of the earth.”

In 2005, marine biologists Tsunemi Kubodera and Kyoichi Mori presented the first underwater photographs of a live giant squid in its natural habitat. For a time it was thought that squid might catch their prey through trickery—by hovering in the water column with tentacles extended until some unwary fish or smaller squid stumbled into their trap. But the images show the large squid aggressively attacking a baited line. The idea that Architeuthis is a laid-back, deep-sea drifter began to give way to an image of a quick and agile predator. The first video footage came in December of the following year, when scientists from the National Science Museum of Japan recorded a live giant squid that had been hauled up to the surface next to the boat. Video footage of giant squid in their natural, deep-sea environment is still being sought, but the photos and video already obtained give tantalizing glimpses of an enigmatic animal that has inspired myths and legends for centuries. The squid are not man-eating ship sinkers, but capable predators in an utterly alien world devoid of sunlight. No new images have surfaced since 2006, which seems typical of this mysterious cephalopod. Just when we catch a brief glimpse, the giant squid retreats back into the dark recesses of its home, keeping its mysteries well guarded.

Further reading:

Ellis, R. 1994. Monsters of the Sea. Connecticut: The Lyons Press.

Ellis, R. 1998. The Search for the Giant Squid. New York: Penguin.

Guerraa, Á; Gonzáleza, Á.; Pascuala, S.; Daweb, E. (2011). The giant squid Architeuthis: An emblematic invertebrate that can represent concern for the conservation of marine biodiversity Biological Conservation, 144 (7), 1989-1998

Kubodera, T., and Mori, K. 2005. First-ever observations of a live giant squid in the wild. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 22 (272). pp. 2583-2586

Lee, H. 1883. Sea Monsters Unmasked. London: William Clowes and Sons, Limited

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)