Strange Rain: Why Fish, Frogs and Golf Balls Fall From the Skies

Unusual precipitation doesn’t just belong in myth and legend, and it’s more common than you might think

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/59/58595ce8-2e34-4e19-ad04-b1de10715820/42-34984749.jpg)

Earlier this year, a milky white rain coated cars, windows and people in parts of Washington, Oregon and Idaho. The precipitation wasn’t dangerous, but it was a bit of a mystery.

Rain isn’t pure water, because precipitation can’t form without some sort of particle to act as a nucleus, which gathers water molecules from the air until the drop gets heavy enough to fall. But sometimes rain is a lot dirtier than normal. Brian Lamb, an air quality specialist at Washington State University, and his colleagues thought that the milky rain might be due to one of the wildfire burn scars they were studying in the Pacific Northwest.

“If a windstorm comes along with the right conditions, you can produce really huge dust and ash plumes from these burn scars,” he says. But the team couldn’t trace the milky rain to one of those sites. Eventually, scientists found the source—a dust storm had whipped up particles from a shallow lakebed in southern Oregon that had a high amount of saline, similar to the composition of the milky rain.

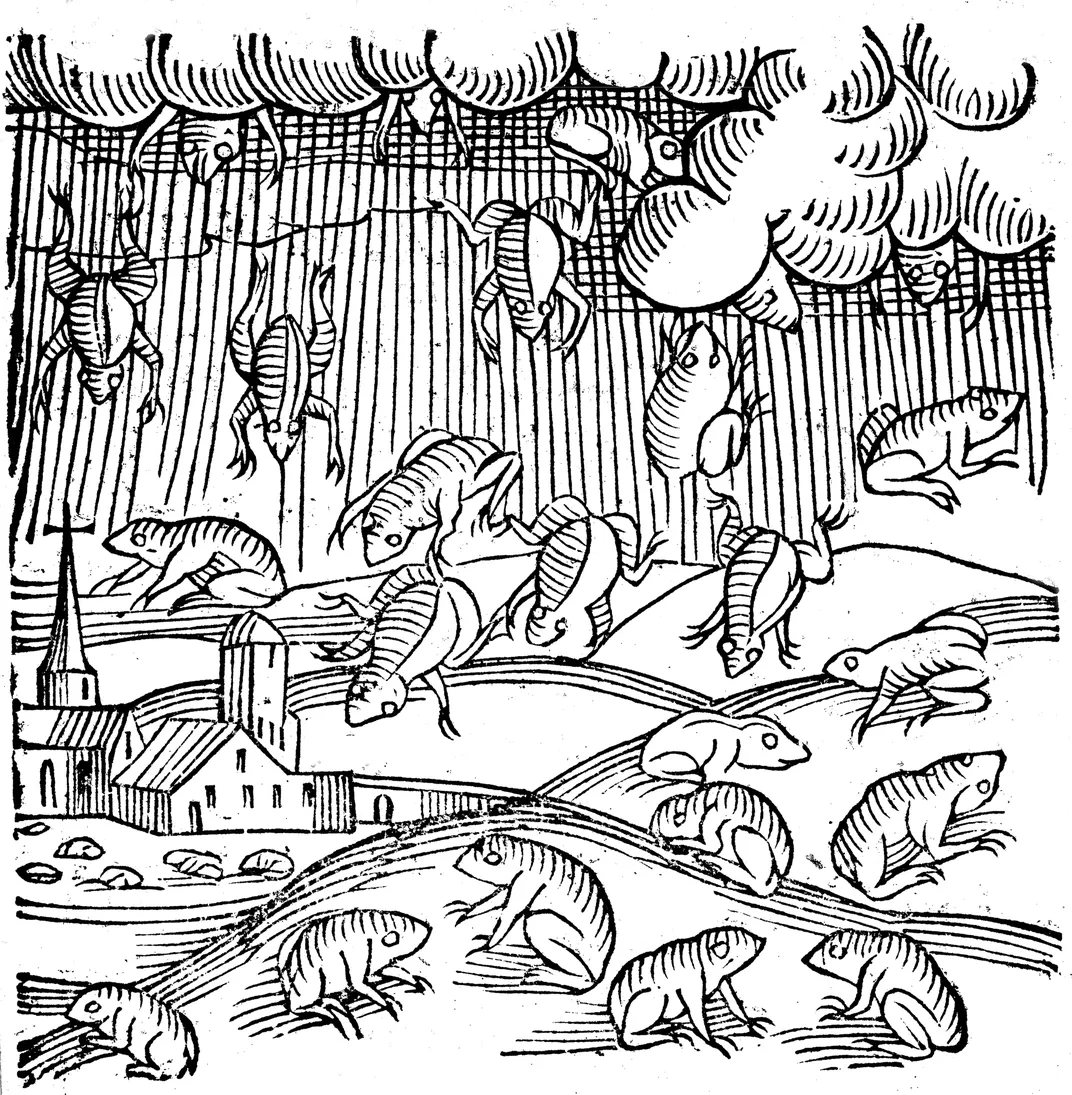

This unusual weather in the Pacific Northwest is just the latest in a long history of weird rains that may have scientific backing, according to Rain: A Natural and Cultural History. “Frog and toad rains, fish rains and colored rains—most often red, yellow or black—are among the most common accounts of strange rain, reported since ancient times,” author Cynthia Barnett notes in the book.

Heraclides Lembus, a Greek philosopher who lived in the second century B.C., writes: “In Paeonia and Dardania, it has, they say, before now rained frogs; and so great has been the number of these frogs that the houses and the roads have been full of them.”

The phenomenon is not restricted to history. The village of Yoro in Honduras celebrates the annual Festival de la Lluvia de Peces, to commemorate the rain of small, silvery fish that allegedly happens at least once a year. And in 2005, thousands of itty-bitty frogs reportedly rained down on a town in northwestern Serbia. “The frogs, different from those usually seen in the area, survived the fall and hopped around in search of water,” according to one news story.

“Still more peculiar rains reported over history have included hay, snakes, maggots, seeds, nuts, stones and shredded meat (that last one is suspected to have dropped from a boisterous flock of feeding vultures),” Barnett writes. She even found one account of a rain of golf balls in Florida—potentially linked to a waterspout crossing over a golf course.

“I always find the frogs and the fish to be weird,” says John Knox, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Georgia. “And I’m not sure we total understand that, but it seems that it has to be that somewhere there’s a waterspout or a tornado … something must have gone over a lake, sucked up a bunch of fish” or other material and dropped it somewhere else.

How far an object travels depends on shape, weight and wind, Knox says. In his studies of tornado debris, he has documented printed photographs that traveled as far as 200 miles and a metal sign that flew about 50 miles. “That sign went up and did the magic carpet ride,” landing in the next state, he says.

Dust, the usual culprit behind oddly colored rains, can travel a lot farther. Yellow dust that fell on western Washington in 1998 was traced to the Gobi Desert. And the Sahara can spread its dust thousands of miles across the Atlantic. “If that dust plume interacts with some precipitation, then you’ve got the ingredients where the dust is washed out in rainfall,” says Lamb. “The color of the rain will probably reflect the mineral composition of the source.”

The Saharan dust produces red rains, for instance, and the Gobi Desert yellow ones. Black rains can come from volcanoes or from pollution. Dirty, greasy rains that turned sheep black in 19th-century Europe were linked to the soot from the great manufacturing centers in England and Scotland. And in more recent history, the burning of Kuwaiti oil wells in the Gulf War in 1991 caused black rain and snow to fall in India.

The source of colored rains is not always clear. A mysterious red rain has sometimes fallen on the southwest coast of India. “People have observed red stains so rich they can stain white clothes pink,” Barnett writes. Researchers have found tiny red particles in the precipitation that look like cells, but what those cells might be has yet to be determined.

And there is one yellow rain that fell on villages in Laos in 1978 that has people still arguing over what actually happened. Refugees claimed that the substance fell from planes or helicopters, and some experts suspected that it was a chemical weapons attack. But other scientists proposed a different cause: mass “defecation flights” by honeybees that rained yellow bee feces.

But while rains of objects or colored rains may seem odd, they are more common than we realize. In the early 20th century, Charles Hoy Fort collected around 60,000 newspaper reports that described falls of everything from frogs and snakes to cinders and salt. Even that milky rain in the Pacific Northwest wasn’t a first for the area, notes Lamb.

“Here in eastern Washington, we’ve experienced those kinds of rains periodically,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)