Snakes in a Frame: Mark Laita’s Stunning Photographs of Slithering Beasts

In his new book, Serpentine, Mark Laita captures the colors, textures and sinuous forms of a variety of snake species

![]()

Rowley’s Palm Pit Viper (Bothriechis rowleyi). This venomous snake, which ranges from two and a half to five feet in length, lives in the forests of Mexico. © Mark Laita.

Mark Laita captured plenty of photographs of snakes striking, their mouths agape, in the making of his new book, Serpentine. But, it wasn’t these aggressive, fear-inducing—and in his words, “sensational”—images that he was interested in. Instead, the Los Angeles-based photographer focused on the graceful contortions of the reptiles.

“It is not a snake book,” says Laita. As he explained to me in a phone interview, he had no scientific criteria for selecting the species he did, though herpetologists and snake enthusiasts will surely perk up when they see the photographs. “Really, it is more about color, form and texture,” he says. “For me, a snake does that beautifully.”

Albino Black Pastel Ball Python (Python regius). This three- to five-foot long constrictor lives in the grasslands and dry forests of Central and West Africa. © Mark Laita.

Over the course of the project, Laita visited zoos, breeders, private collections and antivenom labs in the United States and Central America to stage shoots of specimens he found visually compelling. “I would go to a place looking for this species and that species,” he says. “And, once I got there, they had 15 or 20 others that were great too.” If a particular snake’s colors were muted, Laita would ask the owner to call him as soon as the animal shed its skin. “Right after they shed they would be really beautiful. The colors would be more intense,” he says.

Red Spitting Cobra (Naja pallida). Dangerous to humans, the red spitting cobra of East Africa grows up to four feet in length. © Mark Laita.

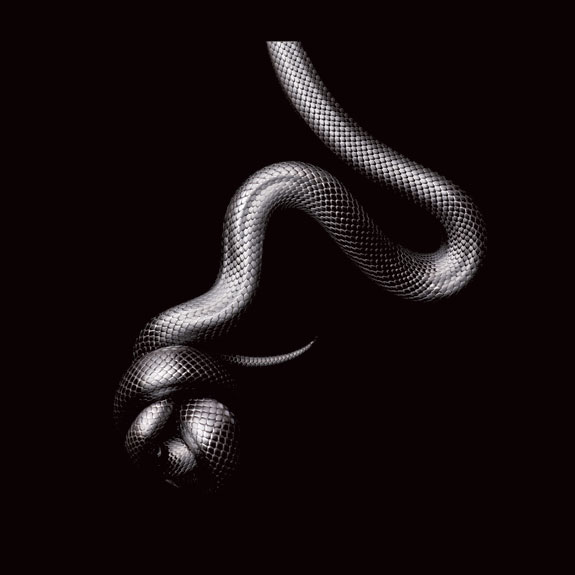

At each site, Laita laid a black velvet backdrop on the floor. Handlers would then guide each snake, mostly as a protective measure, and keep it on the velvet, while the photographer snapped away with an 8 by 10 view camera and a Hasselblad. “By putting it on a black background, it removes all of the variables. It makes it just about the snake,” says Laita. “If it is a red snake in the shape of a figure eight, all you have is this red swipe of color.”

Philippine Pit Viper (Trimeresurus flavomaculatus). This two-foot long, venomous snake is found near water in the forests of the Philippines where it eats frogs and lizards. © Mark Laita.

Without much coaxing, the snakes curved and coiled into question marks, cursive letters and gorgeous knots. ”It is as if these creatures are—to their core—so inherently beautiful that there is nothing they can do, no position they can take, that fails to be anything but mesmerizing,” writes Laita in the book’s prologue.

For Serpentine, the photographer hand-selected nearly 100 of his images of vipers, pythons, rattlesnakes, cobras and kingsnakes—some harmless, some venomous, but all completely captivating. He describes the collection as the “ultimate ‘look, but don’t touch’ scenario.”

Mexican Black Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula nigritus). This North American constrictor can grow up to six feet in length. © Mark Laita.

In his career, marked with the success of having his work exhibited in the United States and Europe, Laita has photographed flowers, sea creatures and Mexican wrestlers. “They’re all interesting, whether it’s in a beautiful, outrageous or unusual way,” he says, of his diverse subjects. So, why snakes then? ”Attraction and repulsion. Passivity and aggression. Allure and danger. These extreme dichotomies, along with the age-old symbolism connected with snakes, are what first inspired me to produce this series,” writes Laita in the prologue. “Their beauty heightens the danger. The danger amplifies their beauty.”

King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah). The massive king cobra, found in the forests of southern and southeastern Asia, can grow up to 18 feet. © Mark Laita.

Laita embarked on the project without any real phobia of snakes. “I used to catch them as a kid all of the time. I grew up in the Midwest where it is pretty hard to find a snake that is going to do too much damage to you,” he says. If he comes across a rattlesnake while hiking in his now home state of California, his first impulse is still to try to grab it, though he knows better. Many of the exotic snakes Laita photographed for Serpentine are easily capable of killing a human. “I probably have a little more fear of snakes now after dealing with some of the species I dealt with,” he says.

Royal Python (Python regius). Nestling its eggs, this snake, also known as a ball python, is the same species as the albino constrictor, shown further above. © Mark Laita.

He had a brush with this fear when photographing a king cobra, the longest venomous snake in the world, which measures up to 18 feet. “It is kind of like having a lion in the room, or a gorilla,” says Laita. “It could tear apart the room in second flats if it wanted to.” Although Laita photographed the cobra while it was enclosed in a plexiglass box, during the shoot it “got away from us,” he says. It escaped behind some cabinets at the Florida facility, “and we couldn’t find it for awhile.”

A black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) biting Laita’s calf. The photographer told Richard Conniff that he wore shorts as opposed to pants because the swishing of his pants might have startled the snake and handlers advised him that there is nothing worse than having a snake slither up a pant leg. © Mark Laita.

He’s also had a close encounter with a deadly black mamba while photographing one at a facility in Central America. “It was a very docile snake,” he recalls. “It just happened to move close to my feet at some point. The handler brought his hook in to move the snake, and he inadvertently snagged the cord from my camera. That scared the snake, and then it struck where it was warm. That happened to be the artery in my calf.” Smithsonian contributing writer Richard Conniff shares more gory details on his blog, Strange Behaviors. Apparently, blood was just gushing from the bite (“His sock was soaked and his sneaker was filled with blood,” writes Conniff), and the photographer said the swollen fang marks “hurt like hell that night.”

Obviously, Laita lived to tell the tale. “It was either a ‘dry bite,’ which is rare, or I bled so heavily that the blood pushed the venom out,” he explained in a publicity interview. “All I know is I was unlucky to be bitten, lucky to have survived, and lucky again to have unknowingly snapped a photo of the actual bite!”

Sign up for our free newsletter to receive the best stories from Smithsonian.com each week.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)