The Scientific Daredevils Who Made Yale’s Peabody Museum a National Treasure

When an award-winning science writer dug into the backstory of this New Haven institute, he found a world of scientific derring-do

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fa/49/fa494e15-0d54-403d-9c50-3af1c5890780/ypmarexhgreathall001web.jpg)

Writer Richard Conniff likes nothing better than to tell a good story. If you spend any time with the long-time correspondent for Smithsonian, you’re in for an earful—the fables and foibles of history, science, technology and literature.

For the past few decades, Conniff has turned his story-telling talents into a kind of one-man industry with copious magazine articles published not only in Smithsonian, but National Geographic, the New York Times, The Atlantic and other prestigious publications. And from his nine books, including Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time, The Ape in Corner Office and The Natural History of the Rich, he's earned his credentials as a passionate observer of the peculiar behaviors of animals, and humans.

For his tenth book, Conniff was asked by Yale University Press to tell the story of the Peabody Museum of Natural History in honor of its 150th anniversary.

Naturally, such a corporate undertaking was met with a degree of journalistic skepticism: “I was a little hesitant at first because I didn’t think I could find a great story or a great narrative arc in one museum.” But then the prize-winning science writer starting digging into the backstory of the New Haven, Connecticut, establishment and what tumbled forth included scandals, adventure, ferocious feuds and some of the wildest, or deranged, derring-do of the scientific world.

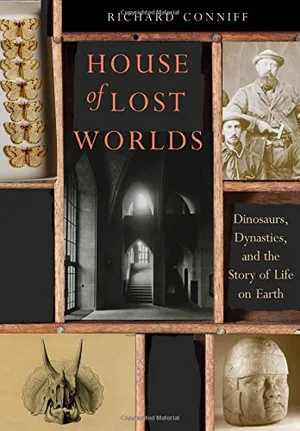

On the occasion of the publication of Conniff’s new book House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties and the Story of Life on Earth, we sat down to discuss the Peabody Museum—the wellspring of some the most distinguished scholarship of our times.

What was the spark that really got you going on this entire project?

I began with John Ostrom and his discovery of the active, agile, fast dinosaurs in the 1960s and the beginning of the dinosaur revolution. His life sort of runs right up through the discovery that modern birds are just living dinosaurs. That was really exciting stuff because he was the guy that really sparked all the things that are in the film, Jurassic Park. So that caused me to think, yeah, there might be a book in this after all. Then I went back and I started to dig.

Recently, for the New York Times, you wrote about a declining appreciation for the natural history museum and its collections: “These museums play a critical role in protecting what’s left of the natural world, in part because they often combine biological and botanical knowledge with broad anthropological experience.” What would you recommend to improve the standing of natural history museums in our country and to improve the political will to embrace them?

I would say that the public does appreciate them on some level. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History gets 7.3 million visitors a year. The American Museum of Natural History in New York gets five million. Everybody goes to these places when they’re kids and the visits form sort of a critical stage in their realization of their place in the world and in cultures. But the people who make decisions about where to spend their government money, for instance, government support like the NSF, the National Science Foundation, which recently suspended its support, and people who are doing philanthropic giving, they don’t see the natural history museums as places where exciting things are happening. I think that the museums themselves have to step forward and make that case and they have to demonstrate how critical their collections are to our thinking about climate change, about mass extinctions, about species invasions and about our own modern great age of discovery. There’s really good stuff to be found there, good stories to be told and people need to hear them.

Yes, the Natural Museum in any town or community is really the wellspring of American scientific research. It’s a tool for showing rather than telling. Give me an example of how well that can work?

There was a kid growing up in New Haven. His name was Paul MacCready. And he got obsessed, the way kids do, with winged insects. So he learned all of their scientific names. He collected them. He pinned out butterflies. He did all that stuff. And he went to the Peabody Museum. Later in life, he became less interested in the natural world and more interested in flight. And he developed the first successful human-powered aircraft capable of controlled and sustained flight—the Gossamer Condor. Then a few years later he developed the first human-powered aircraft to successfully cross the English Channel—the Gossamer Albatross. He was a great hero. This was in the late 1970s. Now, when he came back to visit the Peabody Museum, the one thing he mentioned—he mentioned it casually—was this diorama that he vividly remembered from his youth. It was an image of a dragonfly…a big dragonfly, on the wing over this green body of water. The weird thing is that the Peabody had removed that diorama. But when the archivist there, Barbara Narendra heard about this she went and saved that dragonfly. So they have this chunk of stone basically with that image on it. And it’s just this kind of a stark reminder that the most trivial of things in a museum like this can have profound effects on people’s lives.

Scientists have a tendency sometimes towards petty squabbles. But out of conflict, knowledge is sometimes increased. How is knowledge enhanced by these scientific battles?

Well yes, the one that took place at the Peabody Museum between O. C. Marsh, the paleontologist in the 19th century and his friend—who became his arch rival—Edward Drinker Cope, at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. These two started out hunting for fossils together in the rain in southern New Jersey. It’s not clear how the feud began. They were friends in the 1860s. But by 1872, there were articles in the press referring to this ferocious conflict between them. So competing with each other, they were both driven to collect as much as they could as fast as they could. And that was both good and bad for science because they collected some of the most famous dinosaurs in the world. Take O. C. Marsh at the Peabody Museum, he discovered Brontosaurus, he discovered Stegosaurus, Triceratops, all kinds of dinosaurs that every school kid knows about now. And Edward Drinker Cope was making similar discoveries. Now, the downside was that they raced to discover things and define new species at such a rate that they often described things that later scientists had to spend much of their lives untangling; because there were a lot of species that were given multiple names and that sort of thing, so good and bad sides.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/1a/3a1a5222-8c66-43b2-a2e7-fde5da71a46c/vpar000038-ocmarsh1856.jpg)

Women who have wished to pursue the natural sciences have had a hard row to hoe, but a handful prevailed. Who among them do you most admire and why?

This is one of things that was on my mind regularly while I was doing both my previous book, The Species Seekers, and this book—how ruthlessly women were excluded from scientific discovery. So there was this woman—this is 20th century. But there was this woman—named Grace Pickford and she got a job at Yale and affiliated with the Peabody Museum basically because her husband in the 1920s was G. Evelyn Hutchinson, the “Father of Modern Ecology.” And she was a marine biologist. But she was never made a full staff member. Rather, she was never made a faculty member. She was never promoted in proper order until 1968 when she was on the brink of retirement and they finally made her a professor. But all this time, she had been doing great discoveries of the endocrinology of obscure fish and invertebrates and discovering new species—and the NSF funded her. She had a grant every year. And the other thing about her was that she and her husband eventually divorced and she was not…she did not present herself in a conventional female way. So, in fact, she wore a jacket and tie and sometimes a fedora. By the end of her life she was under pressure to leave and she was given tenure but on the condition that she had to teach the introductory science class. And here was this highly gifted woman, older and not conventional, in her appearance, and in the back of the room these prep school kind of Yalies would be snickering at her, and ridiculing her.

Is there a champion that you came across in your work on this book that somehow missed honor and fame that you would like to see recognized?

You bet. His name was John Bell Hatcher. Nobody has heard of him, but he was this fiercely independent guy who he started out in college paying for his college—I forget exactly where, but he was paying for his college—by mining coal. And, doing that, he discovered paleontological specimens. He transferred as a freshman to Yale, showed his specimens to O. C. Marsh, who saw genius and quickly put him to work. And then after Hatcher graduated from Yale he became an assistant and a field researcher for O. C. Marsh. He traveled all over the West, often alone, and discovered and moved massive blocks containing fossils and somehow extricated them. He removed one that weighed a ton—by himself. And fossils are fragile. He got them back pretty much intact. So he was a bit of a miracle worker that way.

I’ll give you an instance. He noticed that—I mean, it wasn’t just about big fossils, he also wanted the small mammal fossils, microfossils like the jaws and teeth of little rodents. And he noticed that—harvester ants collected them and used them as building material for their nests. He started bringing harvester ants with him. Harvester ants, by the way, are really bad stingers. He took the harvester ants with him to promising sites and he would seed these sites with the ants, and then come back in a year or two and see what they’d done, then collect their work. But in any case, from one nest he collected 300 of these fossils. He was a genius.

He’s the one who actually found Triceratops and Torosaurus and many, many, many other creatures. And he was worked to the bone. He was underpaid by O. C. Marsh and always paid late. He actually paid for his science much of the time by gambling. He was a really good poker player. He was poker faced as they come. He looked like Dudley Do-Right in his 10 gallon hat. And he also…he carried a gun, and knew how to use it in the American west.

I’ll tell you one other story. Hatcher was in Patagonia doing work in the middle of winter. He had to travel 125 miles in the worst weather on horseback alone. At one point he was about to get on his horse and he had to bend down and fix something and the horse jerked its head up and ripped his scalp half off his skull. And he’s alone in the middle of nowhere in wind and cold. He pasted his scalp back across his skull, wrapped kerchiefs around it, pulled his 10-gallon hat tight to hold everything together, got back on his horse, rode 25 miles, slept on the ground that night, rode again the next day and the next day until he finally completed this 125 mile trip. And the only reason he was doing it was to make sure that his fossils were being packed right on a ship to New York.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/9e/379ed73e-af4d-4192-aceb-7e24fbdfa429/ypmar000592-jbhatcher.jpg)

I keep thinking that 19th-century men are just stronger, or at least more stoic, than we moderns are.

Yes, I have to say that his wife, who spent much of her time alone and was the mother of four children, wasn’t so bad off either in terms of strength and stoicism.

New Haven’s Peabody Museum has been called the “Sistine Chapel of Evolution.” Of all these scientists that have haunted these halls, who among them best walks in the footsteps of Charles Darwin and why?

Well, John Ostrom. I mean, John Ostrom, he found this Deinonychus in Montana. And the Deinonychus had this five-inch-long curved claw. From that and from excavating entire fossil skeletons, Ostrom deduced that dinosaurs could be fast, they could be agile, they could be smart; that they weren’t the plodding, swamp bound monsters of 1950s myth. And that began a dinosaur renaissance. That’s why every kid today is obsessed with dinosaurs, dreams about dinosaurs, plays with dinosaurs, reads about dinosaurs. And then his Deinonychus became the model for Velociraptors in Jurassic Park, basically because Michael Crichton, the novelist, thought Velociraptor sounded sexier than Deinonychus. But he did his interviewing research with John Ostrom.

And the other story that I like about Ostrom—in fact, this is really the story that sold me on the book—he was in a museum in the Netherlands in 1970 looking at a specimen that was supposed to be a Pterosaur, like a Pterodactyl. And he looked at it after awhile and he noticed feathers in the stone and he realized it wasn’t a Pterosaur at all; it was an Archaeopteryx, the sort of primal bird from 160 million years ago. In fact it was only the fourth of those known in the world. So he had a crisis of conscience because if he told—he needed to take the specimen home to New Haven to study, and if he told the director, the director of the Netherlands museum might say: “Well, that’s suddenly precious so I can’t let you have it.”

Yet he was, as one of his students described him to me, a squeaking honest man. And so he blurted it out that this was, in fact, Archaeopteryx. And the director snatched the specimen away from him and ran out of the room. John Ostrom was left in despair. But a few moments later the director came back with a shoebox wrapped in string and handed this precious thing to him. With great pride he said: “You have made our museum famous.” So Ostrom left that day full of excitement and anticipation. But he had to stop in the bathroom on the way home; and afterwards he was walking along and thinking about all these things he could discover because of his fossil and suddenly he realized he was empty-handed. He had to race back and collect this thing from a sink in a public toilet. He clutched it to his breast, carried it back to his hotel and all the way back to New Haven and thus saved the dinosaurs’ future…the future for dinosaurs.

So the thing that was important about that fossil was—that Archaeopteryx was—that he saw these distinct similarities between Archaeopteryx and his Deinonychus that is between a bird and dinosaurs. And that link that started in 1970 led to our present day awareness that birds are really just living dinosaurs. So John Ostrom is a very modest guy. You wouldn’t look at him twice if you saw him in the hallways. He’s also one of my heroes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/e8/21e824ee-27a1-4bae-b312-1b30a750e0c4/vpar002530-bakker_b30deinonychus.jpg)

A Google search of the name of the great American philanthropist and businessman George Peabody turns up more than 11 million results, including citations for "The Simpsons." He established the Yale Peabody Museum and numerous other institutions in the U.S. and in London. What is his story?

George Peabody was an interesting character because he had to start supporting his family from when he was, I think, the age of 16, maybe a little younger, because his father died. So at first he was just a shopkeeper in Massachusetts. He improved the shop business, obviously. And then he moved on to Baltimore to a much larger importing business. He eventually became a merchant banker based in London. And he did this thing that was newly possible in the 19th century, really for the first time, which was to build up a massive fortune in a single lifetime. And then he did this thing that was even more radical which was to give it all away.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/3f/d03f2ddd-6b6b-45df-b862-7062b080d4e5/deinonychus-feathered_ntamura.jpg)

No one had done that before?

Not to this extent. George Peabody was really the father of modern philanthropy. So what motivated him, what drove him, kind of what tormented him, was that he had had no education. And he really felt painfully this lack of an education, especially in London in the 19th century. Being an American and traveling in the upper echelon of society, you come in for a fair amount of ridicule or faintly disguised disdain. So, anyway, he gave his money to education. He gave it to the places where he had lived, to Baltimore, to a couple of towns in Massachusetts, one of them is now named Peabody. He gave his money also to housing for the working poor who had come into London during the Industrial Revolution. He gave his money to good causes. And then in the 1860s he was so ecstatic that his nephews—not so much his nieces, but his nephews—were getting an education. So he funded the Yale Peabody Museum in 1866. And he also funded a Peabody Museum of Anthropology at Harvard. And those two institutions are a pretty good legacy on their own but he also has these other legacies distributed all over this country and the UK. And the people that you think of as the great philanthropists, like Andrew Carnegie, well, they were all following in his footsteps.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)