On a recent winter morning at Smithsonian's National Zoo, I watched two Asian elephants take a test. The building was still closed to visitors, but about a dozen zoo staffers were lined up to watch. As the gate from the outdoor elephant yard lifted, a keeper admonished everyone to stand farther back, even though there were bars separating us from the animals. An elephant's trunk has close to 40,000 muscles, and as it’s reaching out to smell you, it can knock you down flat.

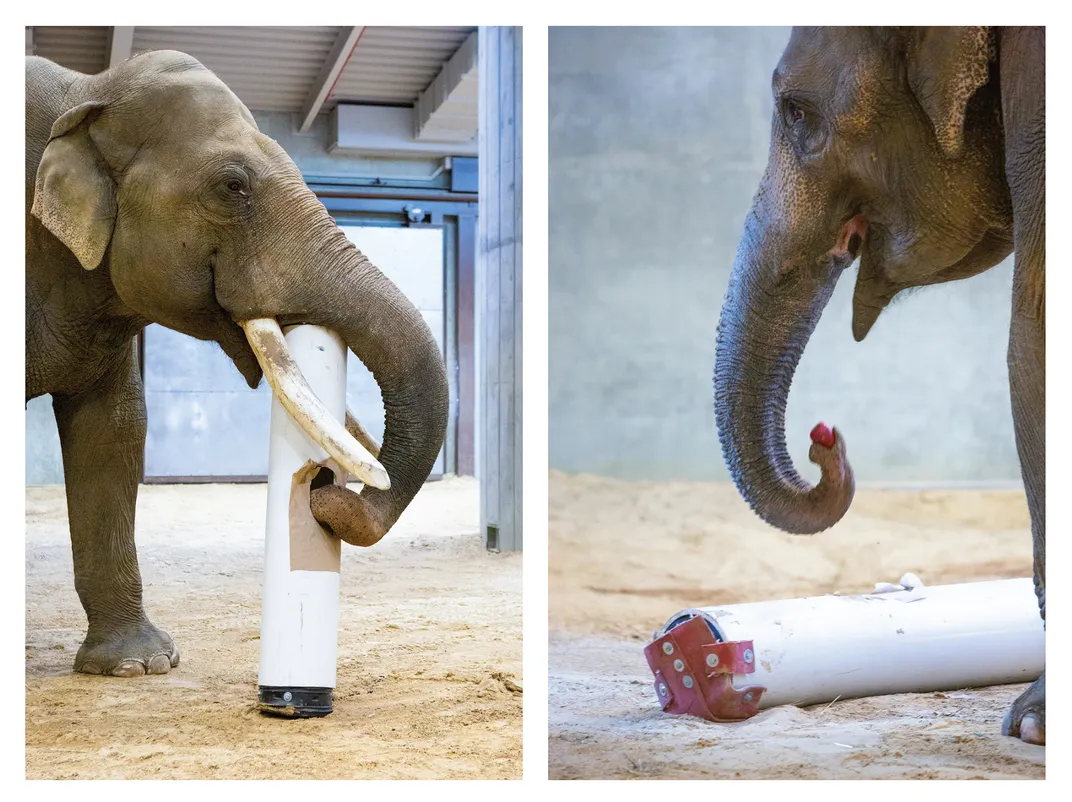

Spike, a 38-year-old bull, ambled in from the yard. He headed straight for a 150-pound PVC pipe in the middle of the dusty floor, wrapping his trunk around it and easily lifting it from the ground. Apples had been stuffed inside three different compartments, and the task was to get to them. As Spike held the strange object upright between his tusks, he groped with his trunk until he found a hole covered with paper in the pipe’s center. He punched through the paper, pulling out the treat. Then a keeper lured Spike outdoors and the gate clanked shut.

Next came 29-year-old Maharani, a spring in her step, ears flapping. She used another strategy, rolling her pipe around until she found an opening at one end. As she was prying off the lid, Spike’s trunk waved through the bars, as though he were beckoning Maharani to come closer. Maharani turned her enormous body around and dragged the pipe along with her, closer to the gate. Then she munched on her apple where Spike could see, or smell, it. The human onlookers giggled in appreciation.

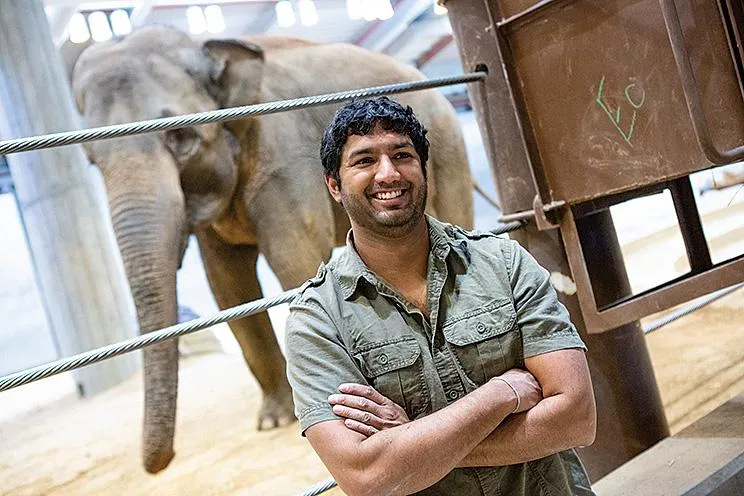

“What we’re looking for is individual difference in elephants—more or less, personality,” explained Sateesh Venkatesh, a 32-year-old graduate student who is researching elephants under the joint supervision of Hunter College and Smithsonian scientists. “Do different elephants react differently to a novel object—to something that’s new, that they haven’t seen? Do they solve the puzzle differently? Are some of them bolder? Do they come straight up to it, pick it up and throw it?”

Elephant research has come a long way since April 1970, when the first issue of Smithsonian featured an Asian elephant on its cover. That original article, by the pioneering zoologist John F. Eisenberg, focused on a Smithsonian Institution expedition to Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. These days, Smithsonian experts who study Asian elephants are concentrating their efforts in Myanmar. Some of their methods are now much more high-tech. Eisenberg’s team risked their lives to put visual tags on just three elephants. Today’s scientists have outfitted dozens of elephants with GPS collars so they can map their movements via satellite.

Half a century ago, the problem Eisenberg outlined was the rapid decline of Asian elephants. The country’s wild population had plummeted from 40,000 at the beginning of the European colonial period in the 1500s to fewer than 3,000 in the late 20th century, largely because of coffee and tea farming. But Eisenberg reported that the situation was looking more promising. Elephants were being bred in captivity and the government was committing more land and water to wild elephant herds.

Today, while the Asian elephant is still listed as an endangered species, its numbers appear to be rising in some regions. By 2011, the elephant population in Sri Lanka was back up to nearly 6,000, according to a census conducted at watering holes. The bigger problem is that the human population has also increased. Sri Lanka, at 25,000 square miles, is about the size of West Virginia, which has fewer than 2 million residents; Sri Lanka has close to 22 million. In other words, elephants in Sri Lanka don’t have much room to wander. Lands they once inhabited have yielded to towns, farms and orchards.

This means humans and elephants are increasingly in conflict. Elephants normally graze in the forest, working hard to fuel their enormous herbivore bodies with grass, bark, roots and leaves. But when they find a field of bananas or sugar cane, they hit pay dirt. Farmers throughout Asia often face heavy financial losses after elephants discover a crop. Sometimes the conflict turns violent. In Sri Lanka, elephants killed around 100 people in 2019. In India, elephant encounters over the past four years have killed more than 1,700 people.

It all comes down to this riddle: How can an enormous animal keep thriving on a continent where space is only getting scarcer? The answer might lie in understanding the elephants themselves, not just as a species but as individuals. What makes one elephant raid a crop field while another stays far away? What are the driving forces behind elephant social groupings? How do bold and demure personality types function in a cohort? Scientists are just starting to explore these questions. But our ability to match wits with the largest-brained land animal might be our best hope for helping it survive.

* * *

Somewhere in Asia, a scene unfolds on a hot July night, as captured by an infrared camera: An elephant, looking pale white on the screen, walks toward a sugar cane field through swarms of insects. Its feet are so thickly padded that its approach is stealthy and silent. When the top of its trunk hits the electrified wire at the edge of the field, it feels the shock and recoils. Then it pauses and seems to make a decision. It lifts its giant foot and stomps the wire to the ground.

On another night, another elephant comes over to a fence and, with the ease of a practiced locksmith, wraps its trunk around the wooden post holding the electric wire in place. It pulls the post out of the ground, throws it down and steps over the wire into the sugar cane paradise on the other side.

“There are a lot of elephants that just go in and eat as slowly and naturally as they would if they were eating in the forest,” says Joshua Plotnik, a longtime animal cognition expert who is Venkatesh’s adviser at Hunter College. “There are other elephants that seem to be much more alert and aware, and so they’ll wait on the periphery and then they’ll go in and eat really quickly and then walk out.”

Does that mean the elephant knows it’s doing something wrong? Is there a frat-boy-like thrill in breaking the rules? “I don’t know if they’re being mischievous,” Plotnik says cautiously. That’s part of what the researchers are trying to figure out: which factors motivate elephants to raid crop fields, apart from hunger alone. Plotnik and others say they’ve seen older bulls do especially aggressive things to get into the fields, like shoving younger elephants through electric fences.

The lab Plotnik runs at Hunter is part of the university’s psychology department, which might seem whimsical, as though Plotnik were performing Freudian psychoanalysis on elephants. Psychology has long included the study of animals—Ivan Pavlov had his dogs, B.F. Skinner had his pigeons, and generations of students have run rats and mice through mazes. The difference is that Plotnik isn’t just using elephant intelligence as proxy for human cognition. He and his students want to understand elephants as elephants.

As easy as it is to find similarities between humans and elephants, there are a lot of important differences. For instance, elephants score much lower than primates do on a test known as the A-not-B challenge. In the classic version of this test, invented by the developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, a researcher hides a toy under Box A and lets a baby find it. Then the researcher moves the toy to Box B while the baby is watching and sees whether the baby knows where to look. Elephants don’t respond well to these visual cues.

But elephants have a sense of smell that’s almost like a superpower. When you come close to an elephant it will point its trunk toward you like a periscope. “He’s exploring his environment, taking in scent,” an elephant keeper at the zoo told me when I asked why a trunk was unfurling in my direction. “Smellevision.” In South Africa, elephants are sometimes trained to sniff out bombs, though there are obvious limitations in using elephants for police or military work. (Try leading an elephant on a leash through a crowded airport or parachuting out of an airplane with one strapped to your chest.)

Some scientists are trying to eavesdrop on elephants by recording their rumbling communications, which are at a frequency too low for the human ear to pick up but can travel through the ground for miles. But Plotnik—who is primarily working with wild elephants in Thailand—and his Smithsonian colleagues in Myanmar are more interested in studying elephant behavior. It makes sense, for instance, that elephants would rather graze in a field of delicious sugar cane than spend all day foraging for roots and bark. But as Venkatesh points out, all the elephants in a given area know the sugar cane is there but only some of them dare to go after it. “What we want to know is—why are some of those individuals interested, and what makes them different from the other ones?”

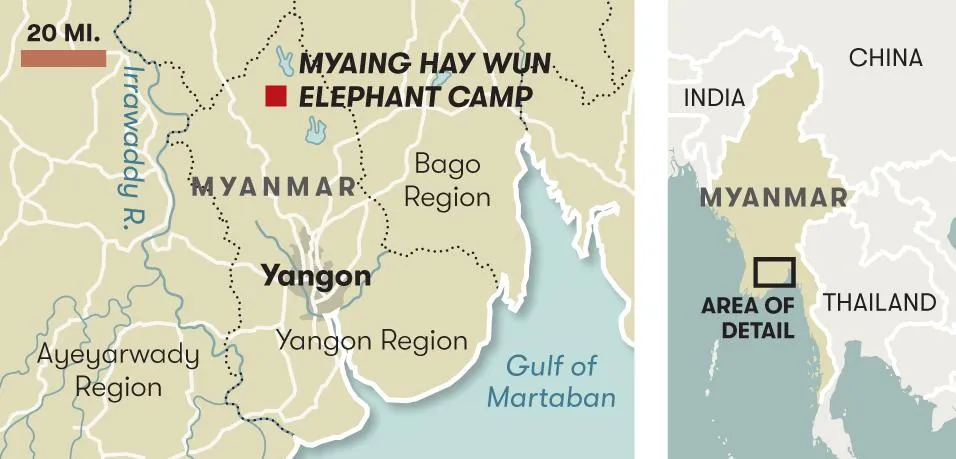

Myanmar is a particularly good place to look for answers because of its large population of semi-captive elephants, which have been living alongside humans since British colonial days, working in the timber industry. These days, logging bans have made their work scarce, and Myanmar isn’t quite sure what to do with the 5,000 or so elephants living in dozens of camps all over the country. They roam in the forests at night, and in the morning, they come back to camp for a morning bath. While they’re out at night, they can cause trouble: In a survey of 303 Myanmar farmers published last year, 38 percent indicated that they’d lost half or more of their crop fields to elephants in the preceding year.

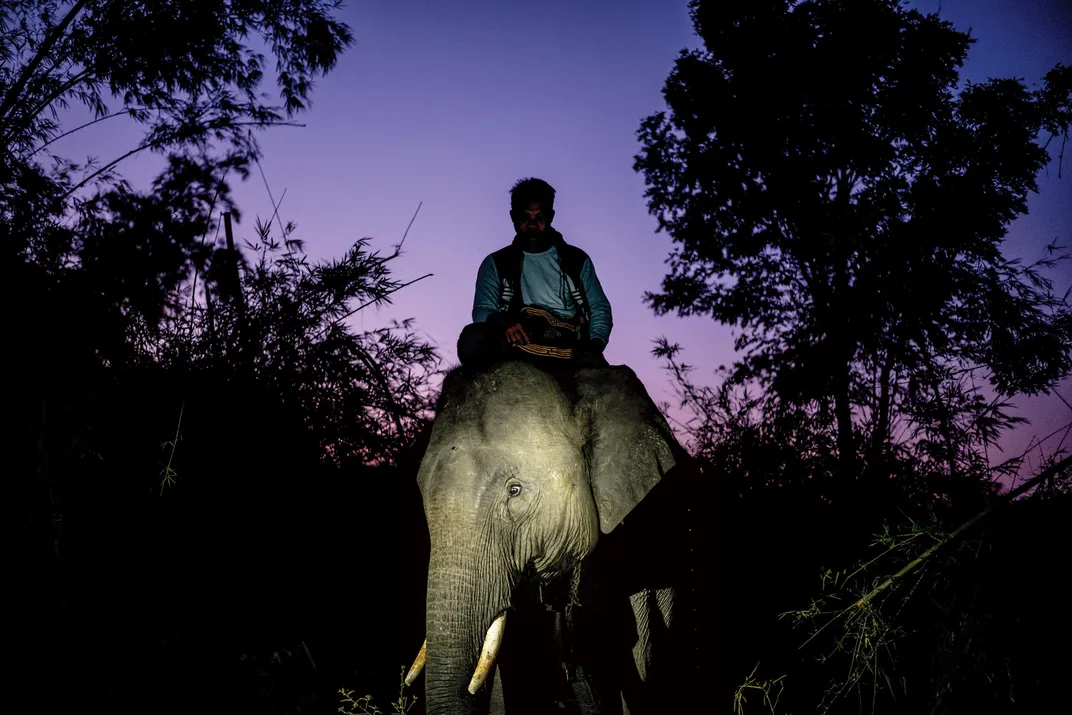

To care for its elephants, Myanmar employs thousands of elephant keepers known as oozis—or, as they’re called in other Asian countries, mahouts. (Outside of Myanmar, most mahouts work at elephant sanctuaries, temples and other places where tourists come to see elephants.) It’s a profession that’s passed on from father to son. Starting in his teens, a boy will get to know a particular elephant—working with it every day, learning its body language and developing the skills to negotiate with it. (Negotiation is necessary. It’s hard to force an elephant to do something it really doesn’t want to do.) The elephants in the camps spend most of their days either restrained by chains near the mahouts’ homes, or with the mahouts themselves riding on their backs.

Scientists in Myanmar rely heavily on local keepers to communicate with the elephants, almost like interpreters. “You can see the relationship,” says Peter Leimgruber, the head of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Conservation Ecology Center. “You see some mahouts who don’t need to do much. You can see the person and the elephant working together in a beautiful way.”

As soon as Venkatesh began giving elephants personality tests, he was struck by the range of reactions. In one early instance, he put a bucket of food in front of an elephant to see if it would lift the lid. Instead, the elephant got impatient and stomped on the bucket, breaking it open. Venkatesh found this endearing. “Because elephants are so highly intelligent, we can see a lot of emotion and thought in what they do,” he says.

Since January 2019, Venkatesh and his colleagues have been giving the PVC-pipe test to elephants in Myanmar to observe problem-solving styles. The researchers are outfitting the same elephants with GPS collars, to track their movements. Is there a correlation between how an elephant performs on the PVC-pipe test and how it acts when it’s roaming around on its own? Do elephants that approached the pipe tentatively also stay farther from the fields? Do the ones who ripped at the pipe aggressively or solve the test quickly also brave the firecrackers and spotlights the farmers set off to scare them away at night?

If elephants who are risk-takers can be identified, maybe the scientists will be able to figure out how to better keep them out of the plantations and thus reduce conflict with people. If the elephants willing to take the biggest risks also have more of a sweet tooth, maybe it will help to throw off their sense of smell by planting citrus trees near a sugarcane farm. Learning all the different methods elephants employ to take down an electric fence would probably be helpful for designing better fences.

“It’s all very idealistic at this point, I have to admit,” says Plotnik. “But it’s a novel approach. How can we figure out which traits are more likely to lead elephants to crop-raid? Can we condition their behavior? Influence their needs? When a child, for example, is told he can’t have the cookies in a cookie jar, he still wants a cookie. But we don’t put up an electric fence in the kitchen to deter our children. We come up with non-harmful, encouraging ways to keep them away from the cookies. I think we can do the same for elephants.”

* * *

One of the scientists contributing to Smithsonian’s elephant research, Aung Nyein Chan, is a 27-year-old graduate student from the Myanmar city of Yangon. His father was a biology teacher and he remembers taking a lot of trips to the local zoo, but he didn’t start spending time with elephants until a few years ago, when he came back from the United States with a bachelor’s degree in wildlife science. Now he’s working toward a PhD from Colorado State University and doing his research at elephant camps in Myanmar, some of them just a few hours from where he grew up.

While I was talking to Chan over Skype, I noticed a picture on his wall of Buddha meditating under the Bodhi Tree. I mentioned a story I’d read about Buddha’s mother, Queen Maya, who dreamed that a white elephant approached her holding a lotus flower in its trunk and then disappeared into her womb. Royal counselors told the queen that the elephant was an auspicious sign, that she was going to give birth to a great king or spiritual leader. Chan smiled. “I think there’s another story about Buddha, that in one of his previous lives he was an elephant.”

Legends like these are one reason some Asian cultures tend to have a soft spot for elephants, in spite of all the trouble they can cause. Hindus worship the elephant-headed god Ganesh, a son of Lord Shiva, who is known as the remover of obstacles. Some Asian countries prohibit the killing of elephants. In Thailand, for instance, the penalty is up to seven years in jail and/or a fine of up to $3,200. Such prohibitions date back as far as 300 B.C., when a Hindu text, the Arthashastra, laid out the rules for building elephant sanctuaries and decreed that killing an elephant there would be punishable by death.

Venkatesh, who grew up in the Boston area but was born in India, notes that the traditional reverence for elephants may not deter angry farmers. “When you’re spending three or four nights a week chasing elephants out of your fields, you might not be thinking about Ganesh at that time.”

In general, poachers, who are primarily interested in ivory, don’t hunt Asian elephants with the same avarice they show African elephants. Female Asian elephants usually don’t have tusks at all, and only some Asian males have prominent ones. But wanton killing does occur. In 2018, the Smithsonian researchers and their partners reported that seven of the elephants they’d fitted with GPS collars in Myanmar had been poached for their meat or skin. “We found entire groups of elephants that had been slaughtered, including calves and cows, and skinned,” said Leimgruber, the Smithsonian conservation biologist. “That’s not a response to an attack.”

Some governments try to prevent retaliatory killings by offering compensation to affected farmers, but that approach is a work in progress. The journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution reported last year that such programs “often face severe criticism due to insufficient compensation, logistical challenges, ineffective governance, a lack of transparency, reduced local understanding of program scope and limitations, and fraudulent claims.”

Chan says some farmers have asked, “Can’t you just take away these elephants?” In some cases, wildlife departments will relocate a particularly troublesome individual. Chan recalls one “naughty” elephant in Myanmar who just couldn’t be deterred. “He wasn’t scared of anyone. So they relocated him about 30 miles north to some other park, but he got back to his old spot in like a day.”

Leimgruber isn’t surprised: “You take an animal, you traumatize it, and then you release it, you just let it go. Well, what would you do if that happened to you? You’d start running, right?”

It might work better to relocate elephants in groups, says Leimgruber. Elephants have strong bonds with their relatives, but they also develop attachments to animals outside their families. Young bulls, for instance, often wander off and attach themselves to older males. In cases where older African elephant bulls have been relocated and younger bulls are left on their own, they’ve acted out—turning violent, attacking rhinos.

Shifra Goldenberg, a Smithsonian researcher who is also Venkatesh’s graduate co-adviser, has spent her career studying elephants’ social bonds. In 2013, a video she released to the public showed several elephants pausing beside the carcass of an elderly female. The elephants paying tribute weren’t related to the deceased, which raised questions about why certain elephants are drawn to each other.

If humans can better understand why elephants stick together—what each one is contributing to the group—it might be easier to help them thrive. “Differences among individuals actually have real-world implications for how they exploit their environments, how they reproduce, how they survive,” Goldenberg says. “It might be better to have a mix of personality types. That way, someone’s bound to figure out the solution.”

* * *

People who spend their lives studying animals don’t always feel obligated to save them. We can study an animal because we want to develop our understanding of evolution, or because we want to find new treatments for human disorders—or simply because the animal is interesting.

But the scientists I spoke to for this story say that satisfying their curiosity isn’t enough. “I mean, this lab’s focus is trying to understand the evolution of cognition and behavioral flexibility,” says Plotnik. “But if you’re going to devote your life to trying to understand an animal that is endangered, I feel like you’re obligated to try and figure out a way that your work can have an impact.”

Leimgruber says this question is a matter of ongoing debate. He himself came to the Smithsonian because of the conservation programs Eisenberg pioneered there. He says many leading Asian elephant researchers in the field today worked either with Eisenberg, who died in 2003, or with one of the people Eisenberg trained. One could even say that conservation was part of the mission of the National Zoo when William Temple Hornaday founded it in 1889 “for the preservation of species.” Still, as late as the 1990s, Leimgruber says there was a distinct group that wanted to keep focusing on the actual science of evolutionary biology and leave conservation up to the lawmakers.

“It’s not really a useful debate,” says Leimgruber, who grew up in a family of foresters in Germany. “I would say everything we do is relevant to conservation, and we work very hard on figuring out how we translate it. It’s one thing to do the research. But if that research then isn’t translated into actions or policies or other things, then it’s useless.”

The young scientists who plan to devote their careers to understanding elephants say they’re optimistic. “We’re looking at more of a holistic view of how animals think and behave,” says Venkatesh. “It’s still a very emerging field—addressing conservation problems from a behavioral perspective. But I think it’s going to yield more effective conservation efforts in the long run. I’m very hopeful.”

Chan remembers how inspired he was when he first started getting to know elephants. “The sound and the presence of them, and being close to something that big in the wild, face to face is just—I don’t know how to describe it. It’s something that can kill you. It’s right next to you, but you don’t want to run away.” He smiles and adds, “I love them.”

The future of elephants on this human-dominated planet really comes down to that one rather unscientific question: How much do we love them? The poet John Donne famously wrote that when one clod of dirt washes away, the entire continent “is the less.” What might ultimately save Asian elephants is the knowledge that if these giant creatures ever stop ambling across their continent—with their wise eyes, their dexterous trunks and their curious minds—humanity will be the less for it.

Editor's note, March 20, 2020: The original version of this article stated that Shifra Goldenberg was the first to document elephant mourning rituals. She was the first scientist to share a video of these rituals with the general public, but other scientists had observed and made note of them before 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/3f/803f0e12-b142-48a7-b27b-7f1ebf4687d1/mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/a9/3da92fb9-ac60-4f6c-bc17-80866533b7bd/longform_desktop.jpg)