One Hundred Years Ago, Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity Baffled the Press and the Public

Few people claimed to fully understand it, but the esoteric theory still managed to spark the public’s imagination

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/1c/c91c3d10-248a-472c-b392-ac593622e442/einstein.jpg)

When the year 1919 began, Albert Einstein was virtually unknown beyond the world of professional physicists. By year’s end, however, he was a household name around the globe. November 1919 was the month that made Einstein into “Einstein,” the beginning of the former patent clerk’s transformation into an international celebrity.

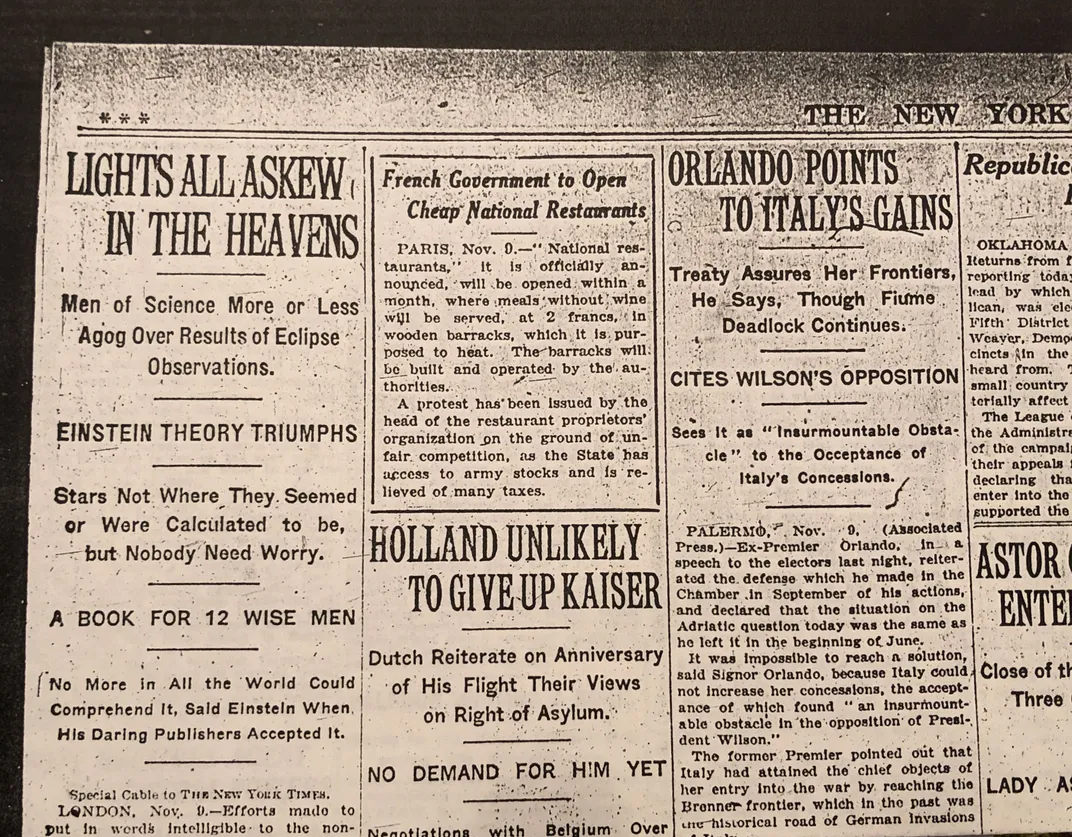

On November 6, scientists at a joint meeting of the Royal Society of London and the Royal Astronomical Society announced that measurements taken during a total solar eclipse earlier that year supported Einstein’s bold new theory of gravity, known as general relativity. Newspapers enthusiastically picked up the story. “Revolution in Science,” blared the Times of London; “Newtonian Ideas Overthrown.” A few days later, the New York Times weighed in with a six-tiered headline—rare indeed for a science story. “Lights All Askew in the Heavens,” trumpeted the main headline. A bit further down: “Einstein’s Theory Triumphs” and “Stars Not Where They Seemed, or Were Calculated to Be, But Nobody Need Worry.”

The spotlight would remain on Einstein and his seemingly impenetrable theory for the rest of his life. As he remarked to a friend in 1920: “At present every coachman and every waiter argues about whether or not the relativity theory is correct.” In Berlin, members of the public crowded into the classroom where Einstein was teaching, to the dismay of tuition-paying students. And then he conquered the United States. In 1921, when the steamship Rotterdam arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, with Einstein on board, it was met by some 5,000 cheering New Yorkers. Reporters in small boats pulled alongside the ship even before it had docked. An even more over-the-top episode played out a decade later, when Einstein arrived in San Diego, en route to the California Institute of Technology where he had been offered a temporary position. Einstein was met at the pier not only by the usual throng of reporters, but by rows of cheering students chanting the scientist’s name.

The intense public reaction to Einstein has long intrigued historians. Movie stars have always attracted adulation, of course, and 40 years later the world would find itself immersed in Beatlemania—but a physicist? Nothing like it had ever been seen before, and—with the exception of Stephen Hawking, who experienced a milder form of celebrity—it hasn’t been seen since, either.

Over the years, a standard, if incomplete, explanation emerged for why the world went mad over a physicist and his work: In the wake of a horrific global war—a conflict that drove the downfall of empires and left millions dead—people were desperate for something uplifting, something that rose above nationalism and politics. Einstein, born in Germany, was a Swiss citizen living in Berlin, Jewish as well as a pacifist, and a theorist whose work had been confirmed by British astronomers. And it wasn’t just any theory, but one which moved, or seemed to move, the stars. After years of trench warfare and the chaos of revolution, Einstein’s theory arrived like a bolt of lightning, jolting the world back to life.

Mythological as this story sounds, it contains a grain of truth, says Diana Kormos-Buchwald, a historian of science at Caltech and director and general editor of the Einstein Papers Project. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the idea of a German scientist—a German anything—receiving acclaim from the British was astonishing.

“German scientists were in limbo,” Kormos-Buchwald says. “They weren’t invited to international conferences; they weren’t allowed to publish in international journals. And it’s remarkable how Einstein steps in to fix this problem. He uses his fame to repair contact between scientists from former enemy countries.”

At that time, Kormos-Buchwald adds, the idea of a famous scientist was unusual. Marie Curie was one of the few widely known names. (She already had two Nobel Prizes by 1911; Einstein wouldn’t receive his until 1922, when he was retroactively awarded the 1921 prize.) However, Britain also had something of a celebrity-scientist in the form of Sir Arthur Eddington, the astronomer who organized the eclipse expeditions to test general relativity. Eddington was a Quaker and, like Einstein, had been opposed to the war. Even more crucially, he was one of the few people in England who understood Einstein’s theory, and he recognized the importance of putting it to the test.

“Eddington was the great popularizer of science in Great Britain. He was the Carl Sagan of his time,” says Marcia Bartusiak, science author and professor in MIT’s graduate Science Writing program. “He played a key role in getting the media’s attention focused on Einstein.”

It also helped Einstein’s fame that his new theory was presented as a kind of cage match between himself and Isaac Newton, whose portrait hung in the very room at the Royal Society where the triumph of Einstein’s theory was announced.

“Everyone knows the trope of the apple supposedly falling on Newton’s head,” Bartusiak says. “And here was a German scientist who was said to be overturning Newton, and making a prediction that was actually tested—that was an astounding moment.”

Much was made of the supposed incomprehensibility of the new theory. In the New York Times story of November 10, 1919—the “Lights All Askew” edition—the reporter paraphrases J.J. Thompson, president of the Royal Society, as stating that the details of Einstein’s theory “are purely mathematical and can only be expressed in strictly scientific terms” and that it was “useless to endeavor to detail them for the man in the street.” The same article quotes an astronomer, W.J.S. Lockyer, as saying that the new theory’s equations, “while very important,” do not “affect anything on this earth. They do not personally concern ordinary human beings; only astronomers are affected.” (If Lockyer could have time travelled to the present day, he would discover a world in which millions of ordinary people routinely navigate with the help of GPS satellites, which depend directly on both special and general relativity.)

The idea that a handful of clever scientists might understand Einstein’s theory, but that such comprehension was off limits to mere mortals, did not sit well with everyone—including the New York Times’ own staff. The day after the “Lights All Askew” article ran, an editorial asked what “common folk” ought to make of Einstein’s theory, a set of ideas that “cannot be put in language comprehensible to them.” They conclude with a mix of frustration and sarcasm: “If we gave it up, no harm would be done, for we are used to that, but to have the giving up done for us is—well, just a little irritating.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/cb/32cbf894-fd61-40e6-a1c5-28f4c81b381f/gettyimages-548803025.jpg)

Things were not going any smoother in London, where the editors of the Times confessed their own ignorance but also placed some of the blame on the scientists themselves. “We cannot profess to follow the details and implications of the new theory with complete certainty,” they wrote on November 28, “but we are consoled by the reflection that the protagonists of the debate, including even Dr. Einstein himself, find no little difficulty in making their meaning clear.”

Readers of that day’s Times were treated to Einstein’s own explanation, translated from German. It ran under the headline, “Einstein on his Theory.” The most comprehensible paragraph was the final one, in which Einstein jokes about his own “relative” identity: “Today in Germany I am called a German man of science, and in England I am represented as a Swiss Jew. If I come to be regarded as a bête noire, the descriptions will be reversed, and I shall become a Swiss Jew for the Germans, and a German man of science for the English.”

Not to be outdone, the New York Times sent a correspondent to pay a visit to Einstein himself, in Berlin, finding him “on the top floor of a fashionable apartment house.” Again they try—both the reporter and Einstein—to illuminate the theory. Asked why it’s called “relativity,” Einstein explains how Galileo and Newton envisioned the workings of the universe and how a new vision is required, one in which time and space are seen as relative. But the best part was once again the ending, in which the reporter lays down a now-clichéd anecdote which would have been fresh in 1919: “Just then an old grandfather’s clock in the library chimed the mid-day hour, reminding Dr. Einstein of some appointment in another part of Berlin, and old-fashioned time and space enforced their wonted absolute tyranny over him who had spoken so contemptuously of their existence, thus terminating the interview.”

Efforts to “explain Einstein” continued. Eddington wrote about relativity in the Illustrated London News and, eventually, in popular books. So too did luminaries like Max Planck, Wolfgang Pauli and Bertrand Russell. Einstein wrote a book too, and it remains in print to this day. But in the popular imagination, relativity remained deeply mysterious. A decade after the first flurry of media interest, an editorial in the New York Times lamented: “Countless textbooks on relativity have made a brave try at explaining and have succeeded at most in conveying a vague sense of analogy or metaphor, dimly perceptible while one follows the argument painfully word by word and lost when one lifts his mind from the text.”

Eventually, the alleged incomprehensibility of Einstein’s theory became a selling point, a feature rather than a bug. Crowds continued to follow Einstein, not, presumably, to gain an understanding of curved space-time, but rather to be in the presence of someone who apparently did understand such lofty matters. This reverence explains, perhaps, why so many people showed up to hear Einstein deliver a series of lectures in Princeton in 1921. The classroom was filled to overflowing—at least at the beginning, Kormos-Buchwald says. “The first day there were 400 people there, including ladies with fur collars in the front row. And on the second day there were 200, and on the third day there were 50, and on the fourth day the room was almost empty.”

If the average citizen couldn’t understand what Einstein was saying, why were so many people keen on hearing him say it? Bartisuak suggests that Einstein can be seen as the modern equivalent of the ancient shaman who would have mesmerized our Paleolithic ancestors. The shaman “supposedly had an inside track on the purpose and nature of the universe,” she says. “Through the ages, there has been this fascination with people that you think have this secret knowledge of how the world works. And Einstein was the ultimate symbol of that.”

The physicist and science historian Abraham Pais has described Einstein similarly. To many people, Einstein appeared as “a new Moses come down from the mountain to bring the law and a new Joshua controlling the motion of the heavenly bodies.” He was the “divine man” of the 20th century.

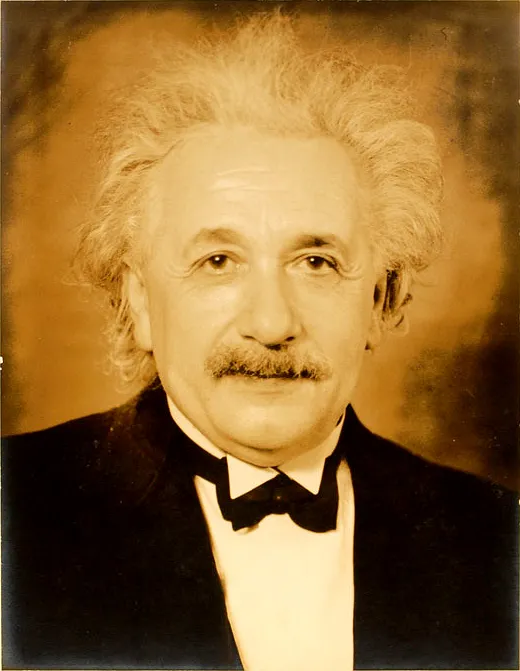

Einstein’s appearance and personality helped. Here was a jovial, mild-mannered man with deep-set eyes, who spoke just a little English. (He did not yet have the wild hair of his later years, though that would come soon enough.) With his violin case and sandals—he famously shunned socks—Einstein was just eccentric enough to delight American journalists. (He would later joke that his profession was “photographer’s model.”) According to Walter Isaacson’s 2007 biography, Einstein: His Life and Universe, the reporters who caught up with the scientist “were thrilled that the newly discovered genius was not a drab or reserved academic” but rather “a charming 40-year-old, just passing from handsome to distinctive, with a wild burst of hair, rumpled informality, twinkling eyes, and a willingness to dispense wisdom in bite-sized quips and quotes.”

The timing of Einstein’s new theory helped heighten his fame as well. Newspapers were flourishing in the early 20th century, and the advent of black-and-white newsreels had just begun to make it possible to be an international celebrity. As Thomas Levenson notes in his 2004 book Einstein in Berlin, Einstein knew how to play to the cameras. “Even better, and usefully in the silent film era, he was not expected to be intelligible. ... He was the first scientist (and in many ways the last as well) to achieve truly iconic status, at least in part because for the first time the means existed to create such idols.”

Einstein, like many celebrities, had a love-hate relationship with fame, which he once described as “dazzling misery.” The constant intrusions into his private life were an annoyance, but he was happy to use his fame to draw attention to a variety of causes that he supported, including Zionism, pacifism, nuclear disarmament and racial equality.

Not everyone loved Einstein, of course. Various groups had their own distinctive reasons for objecting to Einstein and his work, John Stachel, the founding editor of the Einstein Papers Project and a professor at Boston University, told me in a 2004 interview. Some American philosophers rejected relativity for being too abstract and metaphysical, while some Russian thinkers felt it was too idealistic. Some simply hated Einstein because he was a Jew.

“Many of those who opposed Einstein on philosophical grounds were also anti-Semites, and later on, adherents of what the Nazis called Deutsche Physic—‘German physics’—which was ‘good’ Aryan physics, as opposed to this Jüdisch Spitzfindigkeit—‘Jewish subtlety,’ Stachel says. “So one gets complicated mixtures, but the myth that everybody loved Einstein is certainly not true. He was hated as a Jew, as a pacifist, as a socialist [and] as a relativist, at least.” As the 1920s wore on, with anti-Semitism on the rise, death threats against Einstein became routine. Fortunately he was on a working holiday in the United States when Hitler came to power. He would never return to the country where he had done his greatest work.

For the rest of his life, Einstein remained mystified by the relentless attention paid to him. As he wrote in 1942, “I never understood why the theory of relativity with its concepts and problems so far removed from practical life should for so long have met with a lively, or indeed passionate, resonance among broad circles of the public. ... What could have produced this great and persistent psychological effect? I never yet heard a truly convincing answer to this question.”

Today, a full century after his ascent to superstardom, the Einstein phenomenon continues to resist a complete explanation. The theoretical physicist burst onto the world stage in 1919, expounding a theory that was, as the newspapers put it, “dimly perceptible.” Yet in spite of the theory’s opacity—or, very likely, because of it—Einstein was hoisted onto the lofty pedestal where he remains to this day. The public may not have understood the equations, but those equations were said to reveal a new truth about the universe, and that, it seems, was enough.