The Most Famous Dogs of Science

These iconic canines have helped scientists make key discoveries, from archeological finds to cures for disease

:focal(388x428:389x429)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/74/0e74ac8f-8ec1-4eda-b2c3-d929dffe76b8/chaser.jpg)

Anthropologist Grover Krantz dedicated his body to science on the condition that his beloved Irish wolfhound Clyde went with him—he wanted their bond to be remembered and their skeletons to aid forensics research. Archaeologist Mary Leakey’s Dalmatians followed her to remote field sites where they would alert the team to dangerous wild predators. In addition to being faithful companions to scientists, dogs have participated in centuries’ worth of scientific discoveries and innovations. Involving dogs in some forms of science remains an ethical quandary because canines are intelligent, emotive beings, but scientists still use them in biomedical and disease research and pharmaceutical toxicity studies for many reasons, including because dogs’ physiology is closer to ours than rats’ physiology is. Dogs working in science today also identify invasive species, aid in wildlife conservation and even help sniff out early signs of COVID-19 illness. As the number of duties for dogs in science continues to grow, it’s worth looking back at key canine contributions to the field.

Robot

The caves at Lascaux in southwestern France are famous for containing some of the most detailed and well-preserved examples of prehistoric art in the world. More than 600 paintings created by generations of early humans line the cave walls. But if it wasn’t for a white mutt named “Robot” who, by some accounts discovered the caves in 1940, we may not have known about the art until many years later. Marcel Ravidat, at the time an 18-year-old mechanic’s apprentice, was out walking with Robot when the dog apparently slipped down a foxhole. When Ravidat followed Robot’s muffled barks, he recovered more than just the dog—Robot had led him to one of the biggest archaeological finds of the 20th century.

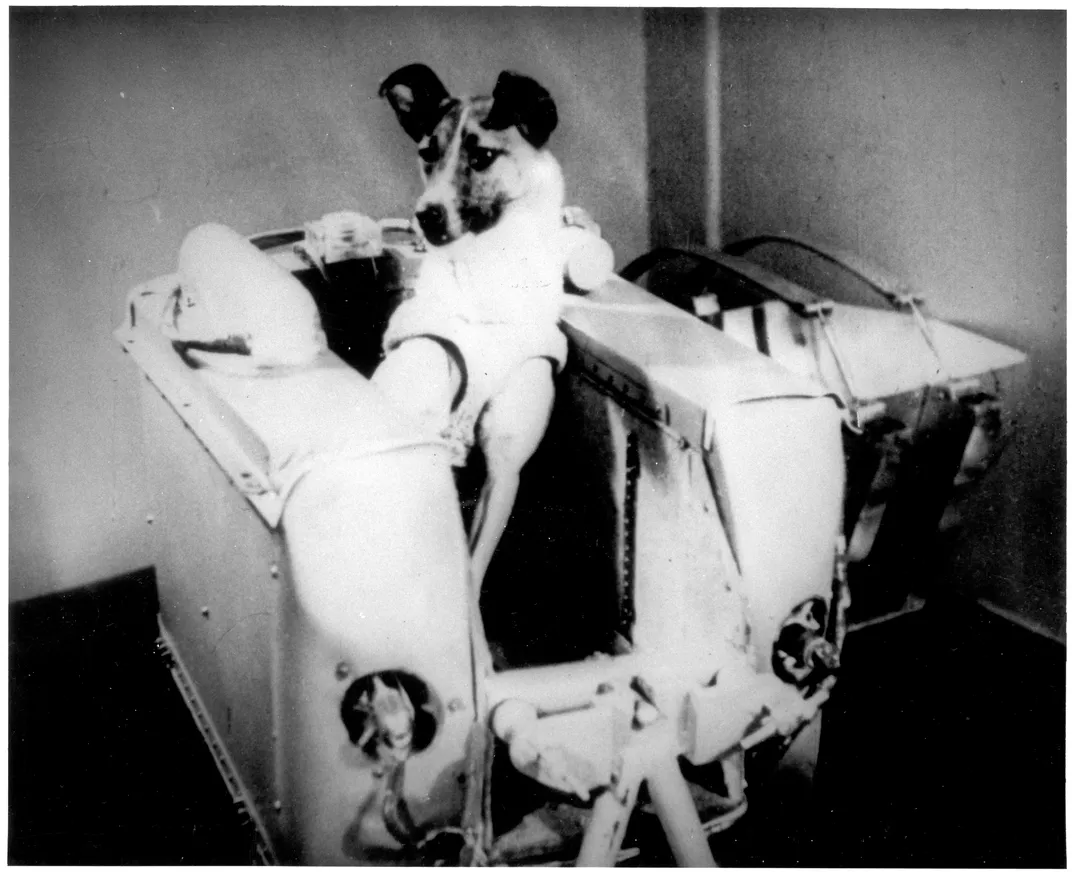

Laika

A stray rescued from the streets of Moscow, Laika became the first dog to orbit the earth in 1957. Between 1951 and 1952, the Soviets began sending pairs of dogs into space, starting with Dezik and Tsygan. Overall, nine dogs were sent on these early missions, with four fatalities. By the time Sputnik 2 launched with Laika aboard, astrophysicists had figured out how to get the canine astronaut into earth’s orbit, but not how to get her back from space. Once in orbit, Laika survived and circled for a little more than an hour and a half before sadly perishing when the temperatures inside the craft rose too high. Had the capsule’s heat shield not broken, Laika would have died on re-entry. While some protested the decision to send Laika into orbit knowing she would die, others defended the knowledge gained in showing animals could live in space.

Strelka and Belka

In August 1960, the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik 5 capsule into space. Along with mice, rats and a rabbit, two dogs became the first living creatures to go into orbit and return to earth safely. These missions and other animal astronauts paved the way for manned spaceflight. Less than a year after Strelka and Belka’s successful voyage, the Soviets sent human Yuri Gagarin into space. The canine pair went on to live full dog lives, and even had descendants.

Marjorie

Before the mid 1920s, a diabetes diagnosis was considered a death sentence. In 1921, however, Canadian researcher Frederick Banting and medical student Charles Best discovered insulin, which would save millions of human lives. The discovery would not have been possible without the sacrifice of several dogs who had their pancreases removed, essentially causing clinical diabetes. The animals were then treated by Banting and Best with pancreatic extracts. Marjorie was the most successful patient; she survived for more than two months with daily injections.

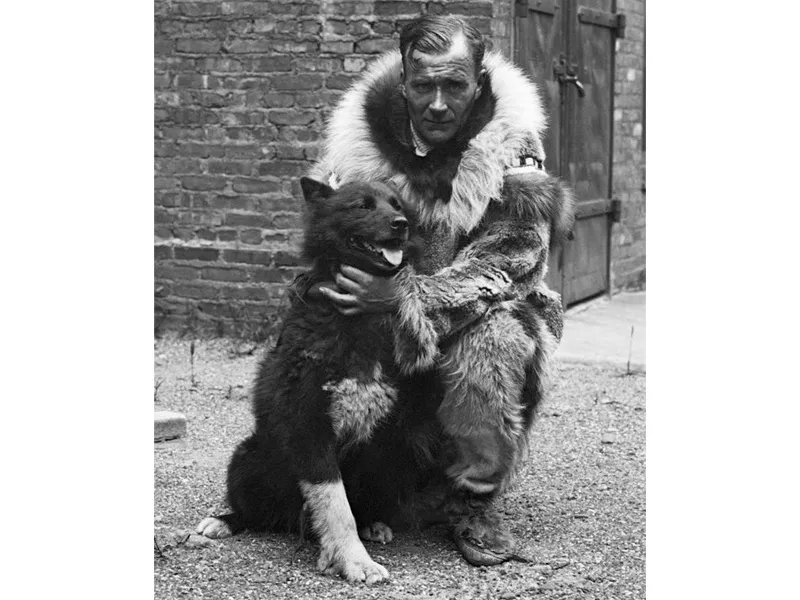

Togo and Balto

In 1925, diphtheria, an airborne respiratory disease that children are especially vulnerable to, swept through the remote Alaskan mining town of Nome. Since no vaccine was available at the time, an “antitoxin” serum was used to treat the disease. But getting it to Nome was a challenge. The nearest supply was in Anchorage, and trains could only bring it to within roughly 700 miles of Nome. More than 100 Siberian husky sled dogs were recruited to transport the serum, among them Togo and Balto. Togo ran double the distance of any dog in the relay and through the most dangerous regions, while Balto finished the last 55-mile stretch, delivering the serum safely to the families in Nome.

Trouve

Alexander Graham Bell’s terrier helped the inventor with his early work. Bell’s father, who worked with deaf populations, encouraged his son to develop a “speaking machine”—advice Bell enacted by manipulating his dog’s bark to sound like a human voice. The younger Bell adjusted his dog’s jowls as Trouve growled to train him to utter what sounded like the phrase “How are you, Grandmama?” Bell went on to become an expert in speech and hearing, and ultimately became most famous for his invention of the telephone.

Chaser

In studying human brain evolution, many researchers look to humans’ unique capability to use a complex system of language for clues about our origins. But the more we study dogs, the more we realize that they, too, may have some clues. Chaser the Border Collie, who died just a year ago at age 15, famously learned to identify 1,022 proper nouns over her lifetime—giving her the largest tested word memory of any non-human animal. Her understanding of language and behavioral concepts provided insight into language acquisition, long-term memory and the cognitive abilities of animals.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)