Life and Rocks May Have Co-Evolved on Earth

A Carnegie geologist makes the case that minerals have evolved over time and may have helped spark life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/88/84882e4c-fab6-42f9-b7de-ab7e5e3173fc/img_0433.jpg)

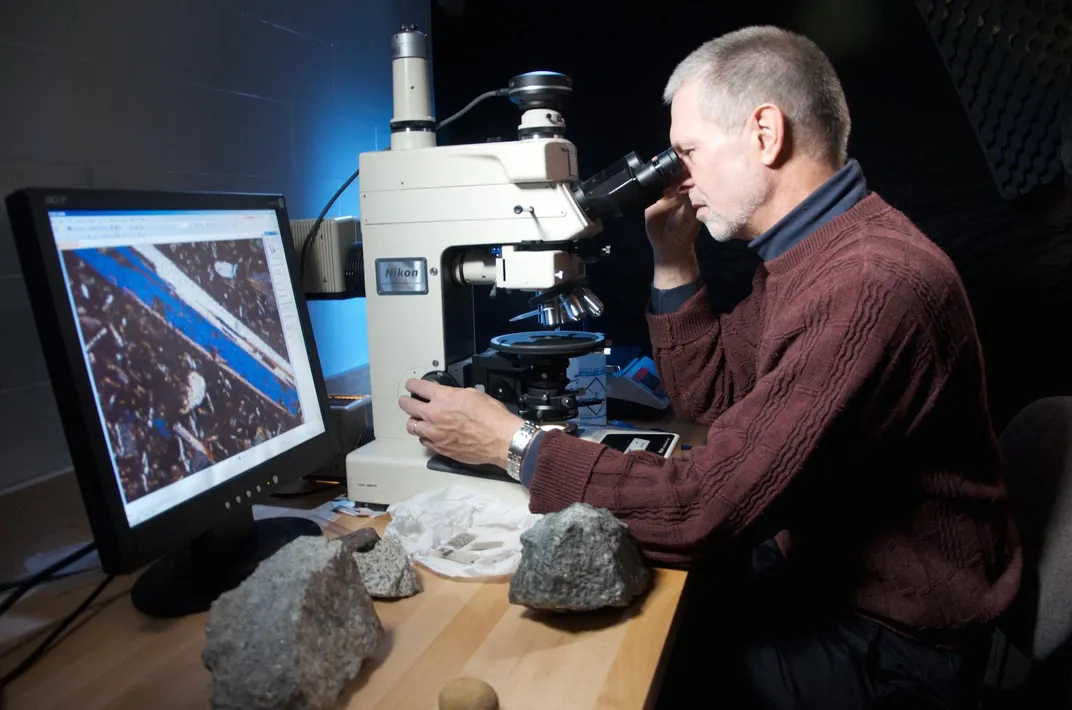

At a Christmas party ten years ago, an idea was brewing in Robert Hazen’s mind. Hazen was a self-proclaimed “hard core” mineral physicist at the time, and like most scientists (and players of 20 Questions), he considered mineral to be a totally separate beast from animal and vegetable. But that was soon to change.

During the party, theoretical biologist Harold Morowitz asked Hazen whether clay minerals existed during the Hadean—the geologic period between 4.6 and 4 billion years ago, when early Earth was forming. Though a basic question, Hazen was taken aback. Morowitz was essentially asking whether the mineralogy that existed when Earth was new, and possibly when life originated, was different from what we see today.

“No mineralogist in history had ever asked a question like that,” says Hazen. While a mineral-forming process should be the same whether it occurred billions of years ago or last Tuesday, Hazen realized there was no reason to assume that minerals couldn’t evolve, just as life changes over time. He and his colleagues have since shown that life didn’t spring up in isolation—minerals likely helped it along the way. And as life evolved, it created a myriad of chemical niches that allowed new minerals to form.

“We see this intertwined co-evolution of the geosphere and biosphere,” says Hazen. “Life begets rock, rocks beget life.” His team and other experts in the field present this idea in a new NOVA feature Life’s Rocky Start. I sat down with Hazen to chat a bit about the film and the amazing world of minerals (the following has been edited for length):

Tell me a little about the film Life’s Rocky Start?

Life’s Rocky Start is the story of Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, told through the eyes of a mineralogist who has undergone a sort of transformation himself. I began as a mineralogist, thinking as most mineralogists do that minerals are beautiful physical objects—they’re varied, they’re diverse. But you can’t tell the story of minerals without also telling the story of life. Today we know of 5,000 or more mineral species—each one a distinctive chemical composition and crystal structure. And of those 5,000, more than two thirds are the result of the changes that life has made to Earth.

So what was the first mineral in the universe?

When we started thinking about minerals through deep time, surprisingly, no one had asked that question. Isn’t that amazing? In any field, origins are a big deal—first life, first planets, first stars. But mineralogists had never asked, what was the first mineral?

Right after the big bang, things are much too hot, and even after things condensed a little bit, it was only hydrogen and helium gas that made up the bulk of the universe. They don’t form minerals because they are gasses, and minerals have to be crystals. The next thing the hydrogen and helium gas did was condense into large stars. Stars are engines of what’s called nucleosynthesis, or making all the chemical elements of the periodic table. Minerals are formed from those other elements.

When after that first star could you have the first crystal? The answer, it turns out, is in the gaseous envelopes of very energetic stars or exploding supernovas. As those gaseous envelopes expand and cool, you have concentrations of elements that are just high enough and temperatures just low enough that the first crystals can form. That first crystal, we think, was a microscopic species of diamond, because stars are carbon rich and because diamond forms at the highest temperature of any known crystal.

What about the first minerals on Earth?

As the gases around the earliest stars cooled, there may be a dozen more different crystals that formed of the commonest elements: silicon, oxygen, magnesium, nitrogen. These were the very first species of mineral crystals that littered the cosmos and formed the dust of those great clouds that eventually formed new solar systems. Earth formed from one of those clouds.

The earliest planets may have had 400 or 500 minerals. Then as planets like Earth evolved over a billion years, we may have gotten up to 1,500 minerals, all forming from pure chemical and physical processes. Beyond that, there’s no other conceivable physical or chemical process that we know of for an Earth-like planet to make more minerals—until you have life.

How did minerals influence early life?

The mineral surfaces protect, organize and template. They take those molecules and select and concentrate them ... they help those molecules react to form longer and longer structures like cell membranes and polymers. We know that molecules simply cannot organize that way in the ocean or atmosphere—they’re much too dilute, they’re much too random. It was surfaces, like minerals, that provided both the energy and the concentration mechanism that’s needed to bring molecules together in the key steps for life’s origin.

The biggest question is: How does one go from molecules organized on a mineral surface to a set of molecules that makes copies of itself? We certainly know that is the fundamental characteristic of life, self-replication, and we know that some early system of molecules must’ve figured out that trick. Perhaps the minerals guided that process or perhaps they were merely a convenient place for molecules to meet and organize, and just by some pure chance event, just the right set of molecules came together and formed this self-replicating system.

Are minerals still evolving today?

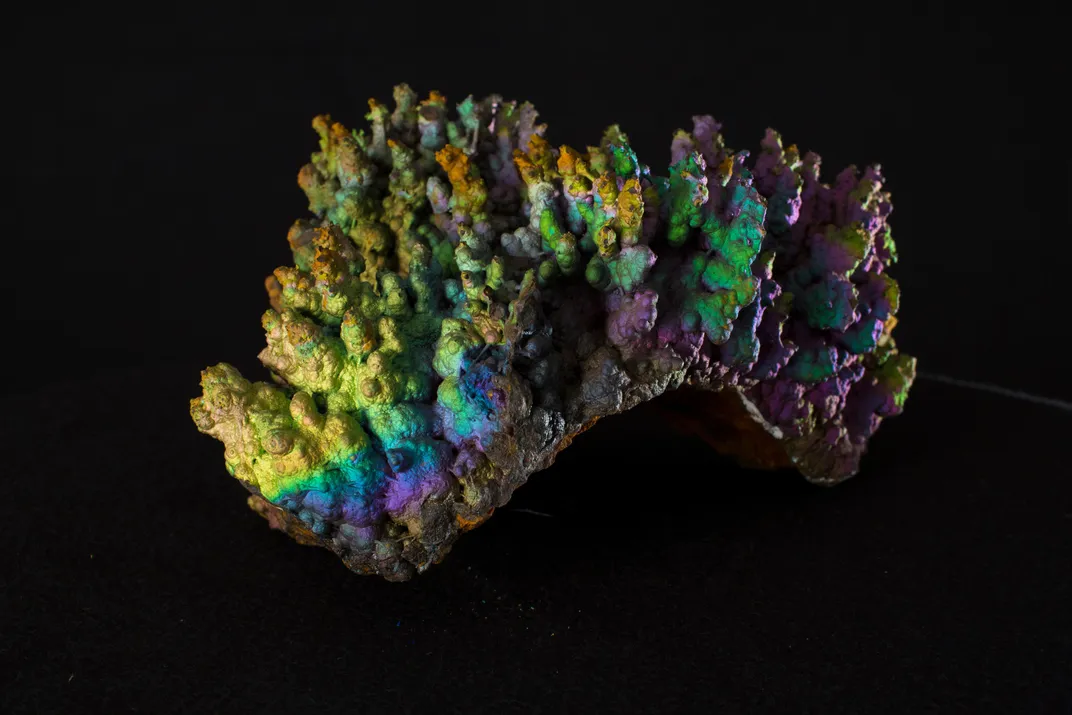

Yes, of course they are. We are entering a period of very rapid evolution due to human activities—the Anthropocene. Humans are altering the near-surface environment, and when you do that you create new chemical niches where minerals can form. We’re changing the geochemical cycle of virtually every element. We mine things, we build things, we shift things and we build chemical plants. One of the consequences of doing this is that new minerals arise.

There are minerals that only occur in mine dumps or acid mine drainages. There are new minerals that only occur on the timbers of mine supports. Landfills now have weathering products of old computer screens and iPhones, which are forming new minerals of rare earth elements that are only just being discovered.

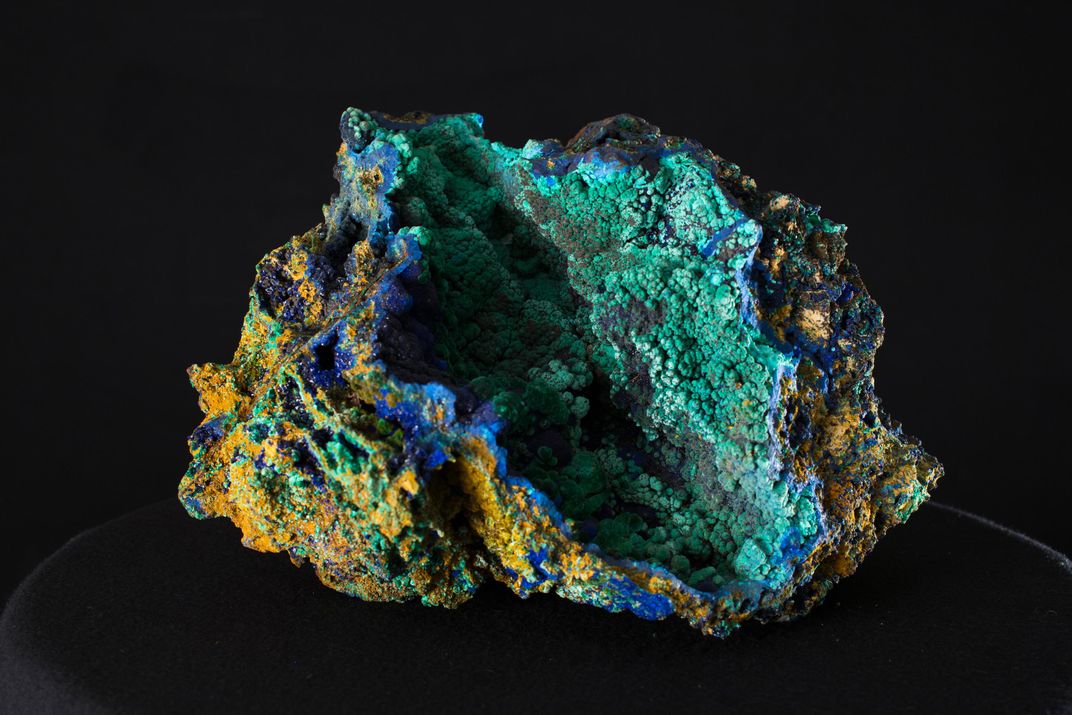

Why should people care about minerals?

Minerals are amazingly wonderful. The film shows that there’s this aesthetic beauty to minerals—a sheer magic. They are important to every facet of society: We would have no technology and none of the conveniences of modern life were it not for the mineral realm. It’s easy to forget that, because we are insulated from the mining and the processing and the chemical treatment of these products. But our modern world is one facilitated by minerals. I think seeing minerals in this richer context of a co-evolving geosphere and biosphere just layers that much more importance and interest on the subject.

For the NOVA documentary, you filmed all over the world. What was your favorite place to visit?

I certainly love Morocco and I’ve been there half a dozen times now. But going to Western Australia—it was a privilege to be in this incredibly remote, incredibly beautiful, although sparse, desolate and dangerous land of the Pilbara. The 3.5-billion-year-old rocks form a little island of ancient Earth that is essentially undeformed. The rocks never experienced the kind of alteration and erosion that is known for virtually all younger rocks.

It’s just an astonishing place. It’s like a pilgrimage for a geologist. To see that and be able to share it with some of the world’s experts is something any geologist would give a great deal to experience. I saw the outcrop first and fresh through my own eyes, but then I learned from them and could see it through the eyes of others who are more experienced. That was a truly transforming experience.

The documentary Life’s Rocky Start will air Wednesday, January 13 at 9 p.m. ET on PBS.

Learn about this research and more at the Deep Carbon Observatory.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)