Lice-Filled Dinosaur Feathers Found Trapped in 100-Million-Year-Old Amber

Prehistoric insects that resemble modern lice infested animals as early as the mid-Cretaceous, living and evolving along with dinosaurs and early birds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/59/54591753-b667-43c1-a6f3-3e85c46b7985/photo-01.jpg)

Anyone who’s had to deal with a lice infestation knows how annoying the persistent little pests can be. But humans are far from the first animals to suffer at the expense of these hair- and feather-inhabiting parasites. As far back as the Cretaceous period, insects that resemble modern lice lived and fed on the bodies of dinosaurs.

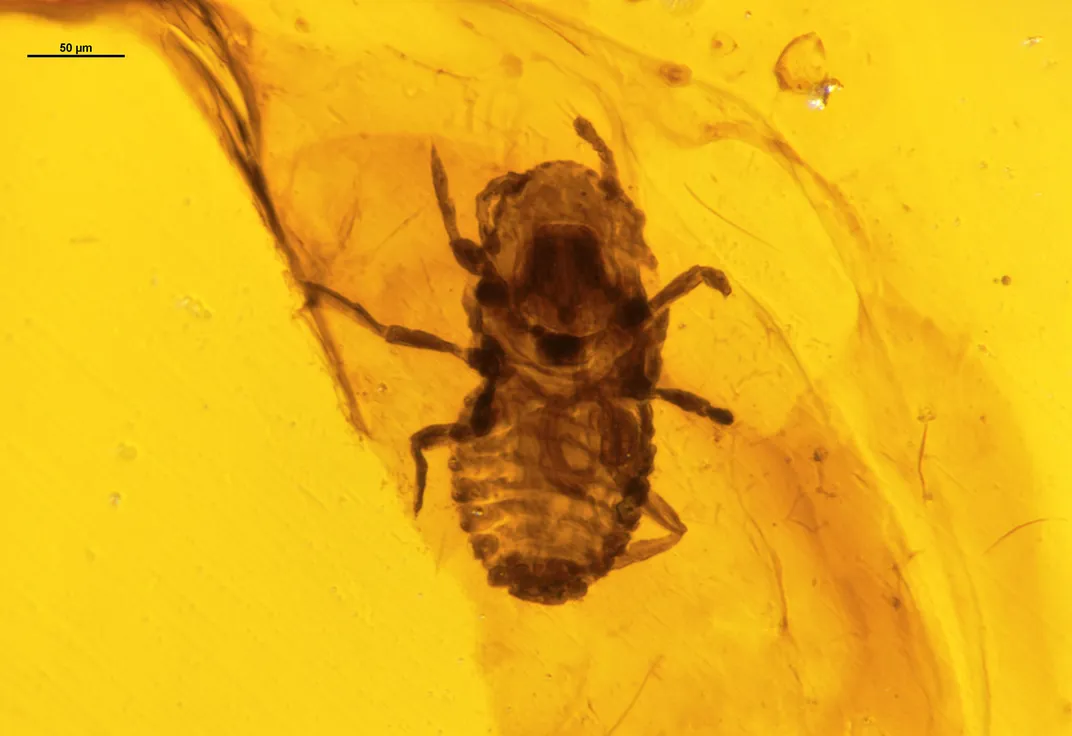

Scientists examining amber fossils discovered 100-million-year-old insects preserved with the damaged dinosaur feathers on which they lived. The bugs provide paleontologists’ first glimpse of ancient lice-like parasites that once thrived on larger animals’ feathers and possibly hair.

“The preservation in amber is extremely good, so good it’s almost like live insects,” says Chungkun Shih, a paleoentomologist and co-author of a study detailing the new find in Nature Communications.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/33/36334f43-e9ac-4127-92c9-224148e584a8/photo-02.jpg)

While dinosaurs may garner an outsized share of attention, the tiny prehistoric pests and parasites that lived on them are a particular specialty of Shih and colleagues at Capital Normal University (CNU) in Beijing. The scientists are fascinated by insects that spent their lives sucking the blood, or gnawing the skin, hair and feathers of their much larger hosts. Though small in scope, parasitic insects have caused enormous suffering by spreading modern diseases like the plague and typhus.

“In human history you can see that the flea caused the black plague, and even today we are affected by blood sucking or chewing parasites,” Shih says. Studying the ancestors of living ectoparasites, which live on the outside of their hosts, can help scientists understand how these pests evolved over millions of years into the species that live among and on us today.

Some finds have proven surprising. In 2012, CNU researchers reported a new family of huge, primitive fleas—more than two centimeters (three-fourths of an inch) long—that survived for millions of years in northeastern China. The supersized fleas gorged on the blood of Jurassic-period dinosaurs some 165 million years ago.

While it stands to reason that feathered dinosaurs were plagued by lice-like insects just as their living bird descendants are, the newly discovered insects encased in amber are the first example to emerge in the fossil record. The Cretaceous period’s lice-like insects are so small that they have not been found preserved in other fossils.

The earliest bird louse previously known lived in Germany some 44 million years ago, and by that relatively late date the insect had become nearly modern in appearance. Consequently, early forms of lice and their evolutionary history have remained a mystery to scientists.

Shih and colleagues found ten, tiny insect nymphs, each less than 0.2 millimeters long, distributed on a pair of feathers. Each feather was encased in amber some 100 million years ago in what is today the Kachin Province of northern Myanmar. During five years of studying amber samples these two were the only ones found to contain the lice-like insects. “It’s almost like a lottery game, where you win once in a while. And we got lucky,” Shih says.

The bugs may not technically be lice, as their taxonomical relationship to the louse order Phthiraptera is unknown. But the insects in question, Mesophthirus engeli, appear as a primitive species very much resembling modern lice. The ancient bugs have different antennae and leg claws from a modern louse, but their wingless bodies look similar, and they feature the large chewing mandibles that cause so much irritation to their hosts.

One feather shows signs of significant gnawing damage, suggesting that lice had established feather feeding lifestyles in the mid-Cretaceous. The bugs may have evolved to exploit the expansion of feathered dinosaurs and early birds.

Shih says that the team originally thought that the feathers in question belonged to early birds, but an expert on fossil feathers and co-author on the study, Xing Xu, believes that they were actually from non-avian dinosaurs.

“One of the two feathers with feeding damage is consistent with the feathers that have been found alongside a dinosaur tail fragment in Burmese amber, while the other feather seems more similar to those that have been found alongside primitive toothed birds in the deposit,” Ryan McKellar, a curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum who specializes in dinosaur feathers, says in an email. “The authors have made a really strong case for these insects being generalist feeders on feathers from a wide range of Cretaceous animals. It looks as though they have probably found the same group of insects feeding on feathers from both flying and flightless animals.”

Just how big of a scourge were lice during the days of the dinosaurs? With limited evidence, paleontologists can’t say exactly how common the insects were, but Shih believes the rarity of his team’s find is due to difficulties of preservation, not a scarcity of the prehistoric pests.

“Insects have their ways of populating themselves on a host, and at that time there was no insecticide to kill them,” he says. “Basically, they could grow and diversify and populate themselves, so I think that the numbers were probably fairly high.”

Perhaps future amber fossil finds will help illuminate how often dinosaurs suffered from lice. “With any luck, future studies will be able to find these insects as adults, or on feathers that are still attached to an identifiable skeleton in amber, and narrow down the ecological relationships a little,” McKellar says. “In the meantime, it is a neat addition to the growing record of parasites like ticks and mites that have been associated with Cretaceous feathers.”

The find also illustrates just how resilient such parasites are, since the same type of insects have lived at the expense of larger animals for at least 100 million years, even as their hosts died out and were replaced by new animals for the bugs to feed on.