How Do You Clean Up an Ebola Patient’s Home?

Decontaminating biohazard sites can be a tough job, but the hardest microbe to wash away may not be what you think

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/5e/b85e4857-2065-40af-bfbc-2e0830792c9f/42-63093176.jpg)

Four days after Thomas E. Duncan was admitted to the hospital as the first person in America to be diagnosed with Ebola, his Dallas home still sat exactly as he’d left it. “The apartment where he was staying with four other people had not been sanitized and the sheets and dirty towels he used while sick remained in the home,” the New York Times reported. Cleaning contractors, it turned out, were too scared to do the job.

Since then, biohazard cleaners have decontaminated Duncan’s apartment, and they have been quicker to respond to the subsequent two cases of Ebola that are currently confirmed in Dallas, both hospital workers who attended to Duncan. The Washington Post reports that the latest patient reported a fever on October 14, and responders in hazmat suits were at her apartment before dawn the next day to begin cleanup.

Contractors normally hired to mop up crime scenes or dispose of hospital waste have the skills needed to carry out Ebola cleanups, as do healthcare workers. The trick to decontaminating any biohazard site is that there is no all-in-one solution. Just as doctors prescribe medications to treat different diseases, the cleaning methods depend on the type of pathogen present. The microorganism’s biology—specifically, what kind of cell wall it has—determines whether a quick bleach wash-down will do or whether professionals need to beak out the hazmat suits and fumigators.

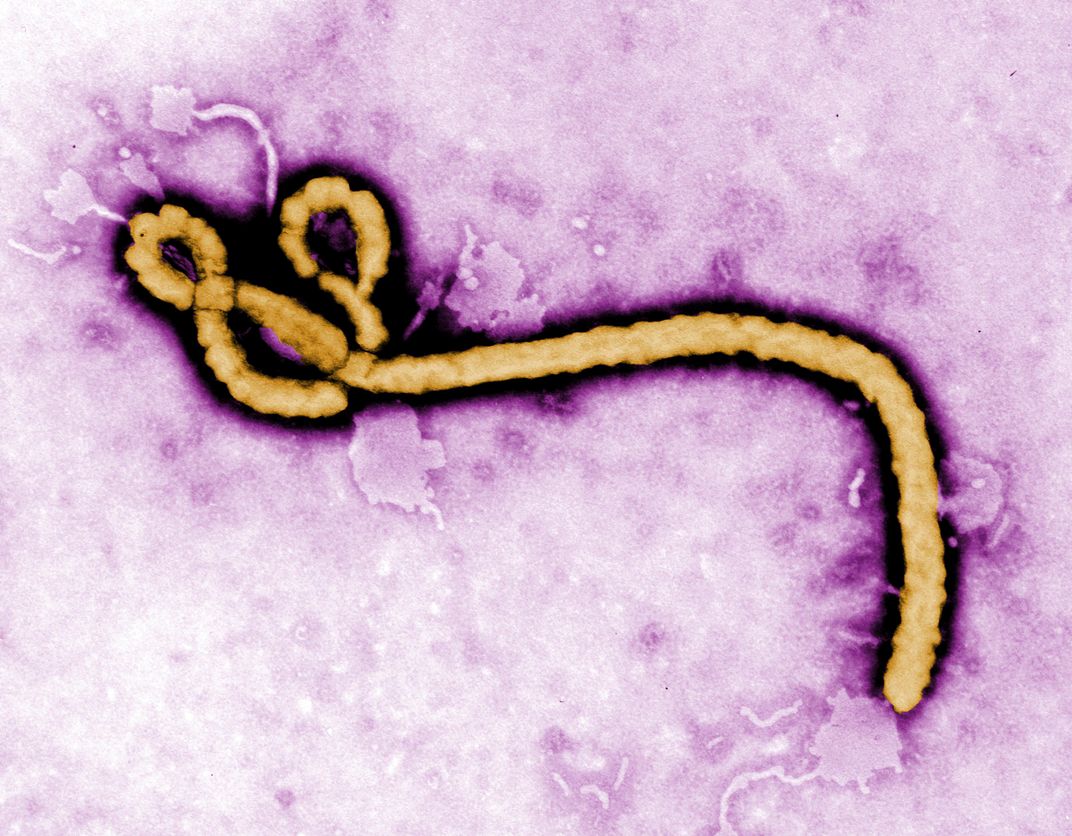

Ebola is spread via contact with bodily fluids, such as blood and vomit, and it can remain infectious for several hours on doorknobs or countertops or for several days in expelled fluids kept at room temperature. But Ebola is an envelope virus—one with a lipid and protein membrane—which means it is vulnerable to many forms of chemical attack. The lipid content means they thrive in water and are prone to drying out. “There is an order of resistance to disinfection,” says Matthew Arduino, chief of the clinical and environmental microbiology branch in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. “Being an envelope virus, Ebola is fairly easy to kill.”

Ebola microbes on their own can be killed off by UV rays from the sun or, if they’re in fluid, by a simple soap-and-water solution, both of which damage the microbe’s membrane. There are no cleaning products designed specifically for Ebola, so professionals can use any hospital-grade disinfectant designed for killing viruses such as polio, norovirus or adenovirus. Those microbes all have a primarily protein membrane so are actually more difficult to kill than Ebola, which means something that can take out polio should be just as effective at eliminating the weaker organism.

In Africa, Arduino has heard that many healthcare workers will use dilutions of sodium hypochlorite—the main ingredient in bleach—ranging from household to professional-grade strength. As an extra precaution, some African hospitals are also treating rooms by filling them with a vapor of the disinfectant hydrogen peroxide, a procedure that takes about two hours to complete. “It’s possibly overkill, but there’s a comfort factor there as well,” Arduino says. Not surprisingly, the Dallas hospital where Duncan was kept opted for the hydrogen peroxide treatment as well.

To clean a patient’s apartment, all biohazard workers need is a PPE—the brightly colored full-body safety suit pictured in so many recent news stories—and the right chemicals. The CDC will soon be issuing formal guidelines for disinfecting Ebola-exposed rooms and homes, Arduino says, but in the meantime, the process is fairly straightforward.

The first step is to remove what professionals refer to as visible bioburdens, such as blood, vomit, and stool. “Soil, blood and other organic materials can interfere with the action of a disinfectant,” Arduino says. After bagging that material up, they wipe down all surfaces that the patient potentially came into contact with and mop the floors. They allow those cleaning products to sit for 2 to 10 minutes, and then the job is done.

The hardest types of microbes to purge are spore-forming gram-positive bacilli such as anthrax and Clostridium difficile. When those organisms enter a harsh environment, they form a thick outer layer containing dipicolinic acid, a chemical that allows them to survive in a dormant state—sometimes for years—until more favorable conditions arise. “When they get into the host, those spores then germinate and the bacteria will grow,” Arduino says.

Getting rid of spore-forming organisms requires toxic concoctions that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) refers to as antimicrobial sterilizers. Those harsh chemicals can be administered as either a liquid or a gas. Following the 2001 anthrax attacks, for example, professionals from the EPA first poured chlorine dioxide on all of the carpet in the exposed buildings and then removed it, because the particle-trapping material is virtually impossible to thoroughly clean. Then they pumped chlorine dioxide gas into the buildings and waited for the amount of potential spores in the air to drop to levels that guaranteed safety. Finally, they took follow-up samples to ensure no traces of anthrax remained.

In the future, people might be spared from almost all contact with cleanup sites. Experts are working on no-touch technologies for sterilizing a hospital room or home. Robots, for example, could use ultraviolet light to disinfect a room contaminated with C. difficile, carrying out the entire process without the presence of a human, Arduino says. Until those breakthroughs come to pass, though, we’ll be largely stuck with a good old-fashioned scrubbing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)