How Albert Einstein Used His Fame to Denounce American Racism

The world-renowned physicist was never one to just stick to the science

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/01/0a01b56c-5583-46c5-86d1-920219b3988e/gettyimages-517359644.jpg)

As the upcoming March for Science gathers momentum, scientists around the country are weighing the pros and cons of putting down the lab notebook and taking up a protest poster.

For many, the call to enter the political fray feels necessary. “Sure, scientific inquiry should be immune from the whims of politicians. It just isn't,” science editor Miriam Kramer recently wrote in Mashable. Others worry that staging a political march will “serve only to reinforce the narrative from skeptical conservatives that scientists are an interest group and politicize their data,” as coastal ecologist Robert Young put it in a controversial opinion article in The New York Times.

But the question of whether scientists should speak their opinions publicly didn't start in the Trump administration. Today’s scientists have a well-known historical model to look to: Albert Einstein.

Einstein was never one to stick to the science. Long before today’s debates of whether scientists should enter politics and controversial scientist-turned-activist figures like NASA’s James Hansen hit the scene, the world-renowned physicist used his platform to advocate loudly for social justice, especially for black Americans. As a target of anti-Semitism in Germany and abroad between the World Wars, the Jewish scientist was well aware of the harm that discrimination inflicts, and sought to use his platform to speak out against the mistreatment of others.

.....

In 1919, Einstein became perhaps the world’s first celebrity scientist, after his groundbreaking theory of relativity was confirmed by British astronomer Arthur Eddington and his team. Suddenly, the man—and not just his science—was front-page news around the world.

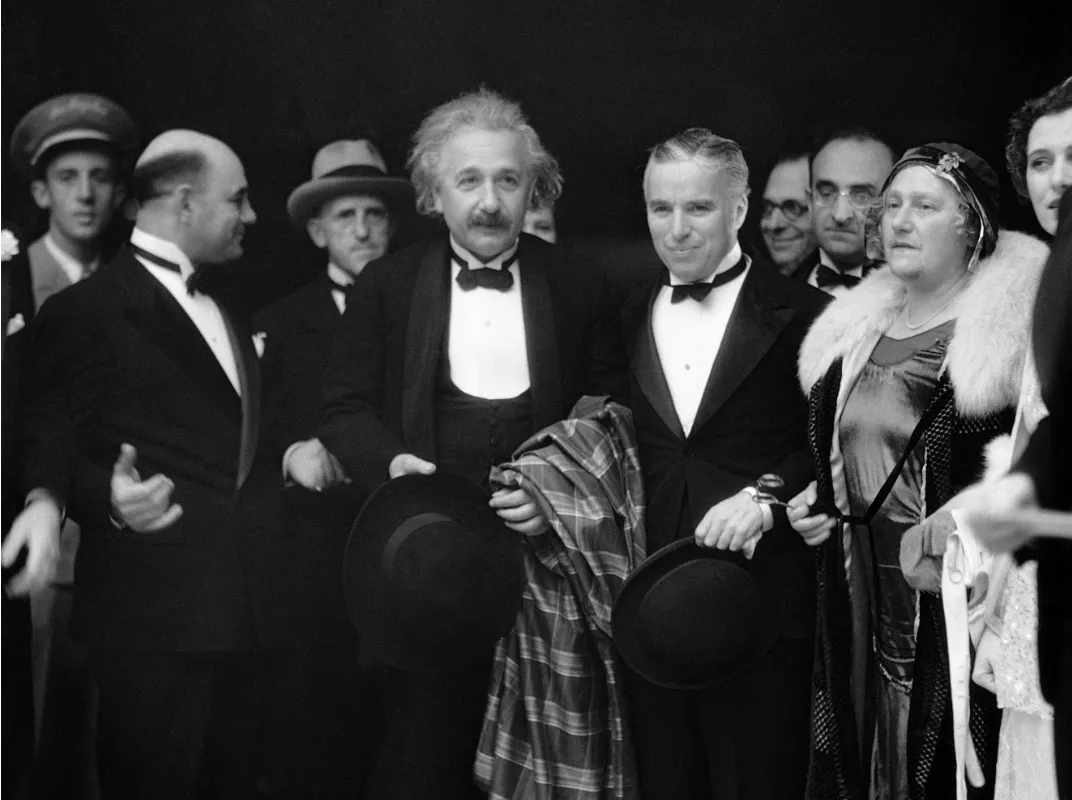

"Lights all askew in the heavens; Men of science more or less agog over results of eclipse observations; Einstein theory triumphs," read a November 20 headline in The New York Times. The Times of London was no less breathless: "Revolution in Science; Newtonian ideas overthrown." J. J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron, called his theory “one of the most momentous, if not the most momentous, pronouncements of human thought.” Einstein's social circles expanded to encompass the likes of Charlie Chaplin and the Queen of Belgium.

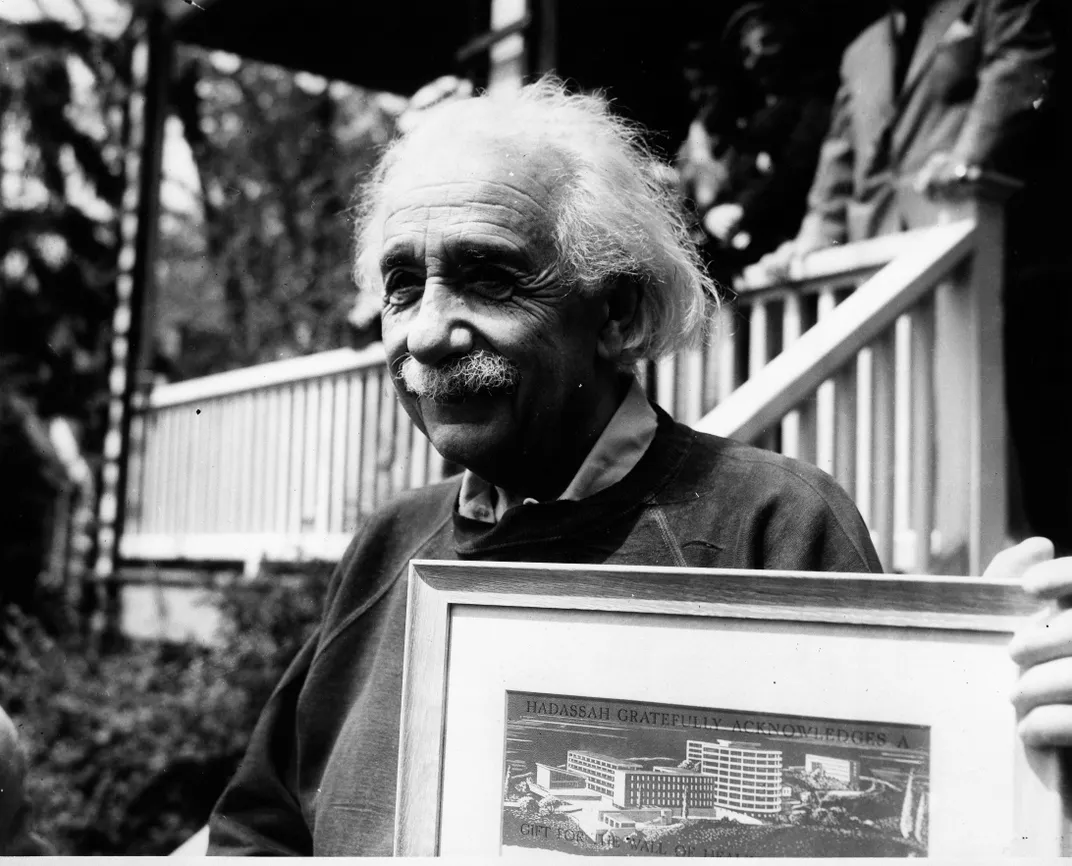

As soon as he had the limelight, Einstein began speaking out. In interviews, he advocated for an end to militarism and mandatory military service in Germany (he had renounced his German citizenship at age 16, choosing statelessness over military service). While he never fully endorsed the Zionist cause, he spoke frequently of his Jewish identity and used his fame to help raise money for the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, making him a very public face not just of science but of Jewishness.

"I am really doing whatever I can for the brothers of my race who are treated so badly everywhere," he wrote in 1921.

His identity politics aroused the ire of many people in Germany, including those who were motivated by nationalism and anti-Semitism. Nobel Prize-winner Philipp Lenard, who eventually became a Nazi, fought hard behind the scenes to make sure Einstein wouldn't win a Nobel himself. Ultimately the Nobel committee decided not to award any physics prize in 1921, partly under anti-Semitic pressures from Lenard and others. (They honored Einstein the following year, giving him the delayed 1921 prize alongside his friend Niels Bohr, who got the 1922 prize.)

In 1929, a German publisher distributed a book titled One Hundred Authors Against Einstein. Although it was primarily a compilation of essays seeking to disprove the theory of relativity, the book also included some openly anti-Semitic pieces.

But it wasn’t just anti-Semitic scientists who criticized Einstein. Fellow scientists, including Einstein’s friends, expressed disapproval of his love of the limelight. "I urge you as strongly as I can not to throw one more word on this subject to that voracious beast, the public," wrote Paul Ehrenfest, Einstein's close friend and fellow physicist, in 1920. Max and Hedwig Born, two other friends, were even more adamant, urging him to stay out of the public eye: "In these matters you are a little child. We all love you, and you must obey judicious people," Max wrote to him the same year.

Just as Einstein's enemies used his Jewish identity to attack his science, Einstein himself drew on his Jewishness to amplify his message about social justice and American racism. "Being a Jew myself, perhaps I can understand and empathize with how black people feel as victims of discrimination," he said in an interview with family friend Peter Bucky. While his political opinions made him a controversial figure, they also got traction, because his words resonated more than most.

Einstein's first aggressive criticism of American racism came in 1931, before Hitler's rise to power. That year, he joined writer Theodore Dreiser's committee to protest the injustice of the "Scottsboro Boys" trial.

In the trial, now one of the most iconic instances of a miscarriage of justice in America, nine African-American teenagers were falsely accused of raping a white woman. Eight were convicted and sentenced to death without evidence or adequate legal defense, and under pressure from armed white mobs. The case was then successfully appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, an effort led by both the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Communist Party. As a result, many white Americans took the wrong side of the case not only out of racism, but out of anti-Communist sentiment.

Robert Millikan, American physicist and Nobel Prize-winner, criticized Einstein for associating himself with left-wing elements in the Scottsboro case, calling his politics “naïve.” (Their disagreement didn't stop Millikan from trying to recruit Einstein for Caltech.) Other Americans were less polite: Henry Ford of car manufacturing fame republished libelous essays from Germany against Einstein.

Also in 1931, Einstein accepted an invitation from the great African-American sociologist and NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois to submit a piece to his magazine The Crisis. Einstein took the opportunity to applaud civil rights efforts, but also to encourage African-Americans not to let racists drag down their self-worth. "This ... more important aspect of the evil can be met through closer union and conscious educational enlightenment among the minority,” he wrote, “and so emancipation of the soul of the minority can be attained."

Yet whatever problems America had with inequality and racism at this time, Europe had problems of its own. In 1933, a well-timed job offer in the states led Einstein to become a citizen of the nation he loved enough to criticize.

Einstein and his wife Elsa left Germany in December 1932. Armed with 30 pieces of luggage, the pair were ostensibly taking a three-month trip to America. But they knew what was coming: In January 1933, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party took full control of the German government.

While the Einsteins were in California, the Nazi government passed a law banning Jews from teaching in universities. "It is not science that must be restricted, but rather the scientific investigators and teachers,” wrote one Nazi official. Only “men who have pledged their entire personality to the nation, to the racial conception of the world ... will teach and carry on research at the German universities.”

In their absence, the police raided the Einsteins' apartment and their vacation cottage under the pretense of looking for weapons. When they found nothing, they confiscated the property and put a $5,000 bounty on the physicist’s head, distributing his picture with the caption "not yet hanged." By the spring of 1933, the most famous scientist in the world had become a refugee.

Einstein was a more fortunate refugee than most. By that time he was already a Nobel Prize winner and media celebrity, recognizable around the world. That fame made him a high-profile enemy for the new Nazi government in Germany, but it also guaranteed him safe places to go. Ultimately he ended up in America at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he would spend the rest of his life.

Einstein saw racism as a fundamental stumbling block to freedom. In both his science and his politics, Einstein believed in the need for individual liberty: the ability to follow ideas and life paths without fear of oppression. And he knew from his experiences as a Jewish scientist in Germany how easily that freedom could be destroyed in the name of nationalism and patriotism. In a 1946 commencement speech at Lincoln University, the oldest black college in the U.S., Einstein decried American racism in no uncertain terms.

“There is separation of colored people from white people in the United States,” said the renowned physicist, using the common term in the day. “That separation is not a disease of colored people. It is a disease of white people. I do not intend to be quiet about it.”

After settling down in America, Einstein continued to publicly denounce American racism. In a 1946 address to the National Urban League Convention, he even invoked the Founding Fathers in his critique. "It must be pointed out time and again that the exclusion of a large part of the colored population from active civil rights by the common practices is a slap in the face of the Constitution of the nation," he said in the address.

The irony of ending in Princeton, one of the most racially segregated towns in the northern U.S., was not lost on Einstein. While no town was free of racism, Princeton had segregated schools and churches, generally following the Jim Crow model in practice if not by law. The University didn't admit any black students until 1942, and turned a blind eye when its students' terrorized black neighborhoods in town, tearing porches off houses to fuel the annual bonfire.

Einstein loved to walk when he was thinking, and frequently wandered through Princeton's black neighborhoods, where he met many of the residents. He was known for handing out candy to children—most of whom were unaware he was world-famous—and sitting on front porches to talk with their parents and grandparents, little-known facts reported in the book Einstein on Race and Racism by Fred Jerome and Rodger Taylor.

Black Princeton also gave him an entrance into the civil rights movement. He joined the NAACP and the American Crusade Against Lynching (ACAL), an organization founded by actor-singer-activist Paul Robeson. At Robeson's invitation, Einstein served as co-chair of ACAL, a position he used to lobby President Harry S. Truman.

He made friends with Robeson, who had grown up in Princeton, and found common cause with him on a wide variety of issues. As Jerome and Taylor note, "almost every civil rights group Einstein endorsed after 1946 ... had Robeson in the leadership." In particular, Einstein joined Robeson and other civil rights leaders in calling for national anti-lynching legislation.

For his anti-racist activism, he was placed under FBI surveillance by J. Edgar Hoover. While Hoover's FBI refused to investigate the Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist organizations, there wasn't a civil rights group or leader they didn't target. By the time of his death, the FBI had amassed 1,427 pages of documents on Einstein, without ever demonstrating criminal wrongdoing on his part.

But to a large degree, his celebrity protected him against enemies like Hoover and more garden-variety American anti-Semites. Hoover knew better than to publicly target Einstein. Einstein used his profile and privilege, volunteering to serve as character witness in a trumped-up trial of W.E.B. Du Bois. His influence had the desired effect: When the judge heard Einstein would be involved, he dismissed the case.

Einstein’s fame afforded him a larger platform than most, and protection from the threats that faced black civil rights leaders. What is remarkable is that, throughout his career, he continued to throw his full weight behind what he saw as a larger moral imperative. "[W]e have this further duty," he said to an audience in the Royal Albert Hall in England in 1933, "the care for what is eternal and highest amongst our possessions, that which gives to life its import and which we wish to hand on to our children purer and richer than we received it from our forebears."