The Man Who Revealed the Hidden Structure of Falling Snowflakes

Beginning in the 1880s, amateur photographer Wilson A. Bentley considered the endlessly varied crystals “miracles of beauty”

At this time of year, children across the northern latitudes are learning an astonishing fact they will remember all their lives. They will pass it on to their children, who will pass it on to their children, on and on as long as there are sleds and skates and drifts and fine freezing days when schools close due to weather. This numinous fact, as basic to childhood as George Washington's cherry tree confession (and far more reliable), is that no two snowflakes are exactly alike.

Think of yourself as a 4- or 5-year-old, hurtling through the pointillist magic of a snowstorm, your tongue out to catch as many falling flakes as you can, hearing that these countless bits of frozen fluff have secret lives, that they are all different, never repeated, despite the clear evidence before your eyes that they are identical and undistinguishable. Someone, perhaps your kindergarten teacher, may have opened a book of photographs of the unreplicated beauty hidden in every flurry.

Almost as incredible, it will turn out, is that one individual is responsible for this wondrous revelation, a man as deserving of a place in that pantheon of those who have revealed something we never knew before as Copernicus, Newton and Curie. Let us add his name to the list: Wilson A. Bentley.

Some years ago, according to Smithsonian archivist Ellen Alers, a colleague, Tammy Peters, came upon a storage box with a label that could serve as the title of a Borges short story: "Memoranda on the New Egg Blower, and Miscellaneous Instruments (accession T90030)." As Alers recalls, "the box seemed to weigh about 75 tons." Inside were indeed egg-blowing tools; several metal photogravure plates depicting scenes from the Harriman-Alaska Expedition of 1899; engraving plates for an 1851 publication on American natural history; and hundreds of glass-plate negatives. Held up to the light, the images revealed rows of sharply etched six-pointed crystals, each unique. "We had no idea where they'd come from," Alers says.

A year or so later, Smithsonian archivist Mike Horsely came across a sheaf of photographic prints depicting snowflakes and marked "W. Bentley." Horsely remembered the glass plates. Negatives and positives were reunited. Wilson Bentley, the archivists discovered, had been a fascinating character.

Were it not for Bentley's tinkering with cameras during the early days of the medium, he might have lived an entirely unremarkable life. Born in 1865, he spent most of his 66 years as a farmer in Jericho, Vermont. Largely self-educated, he was one of those particularly American autodidacts whose natural inquisitiveness, mixed with a touch of eccentricity, led him on an intriguing quest.

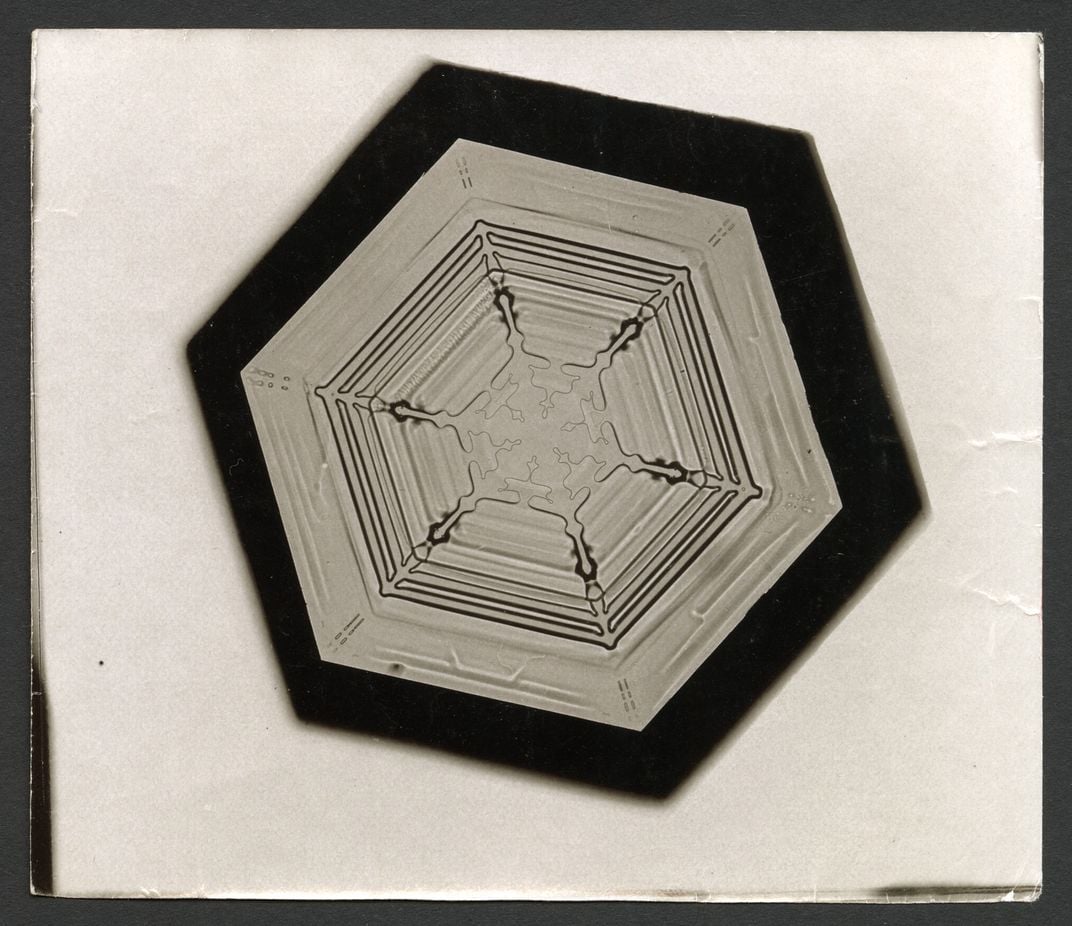

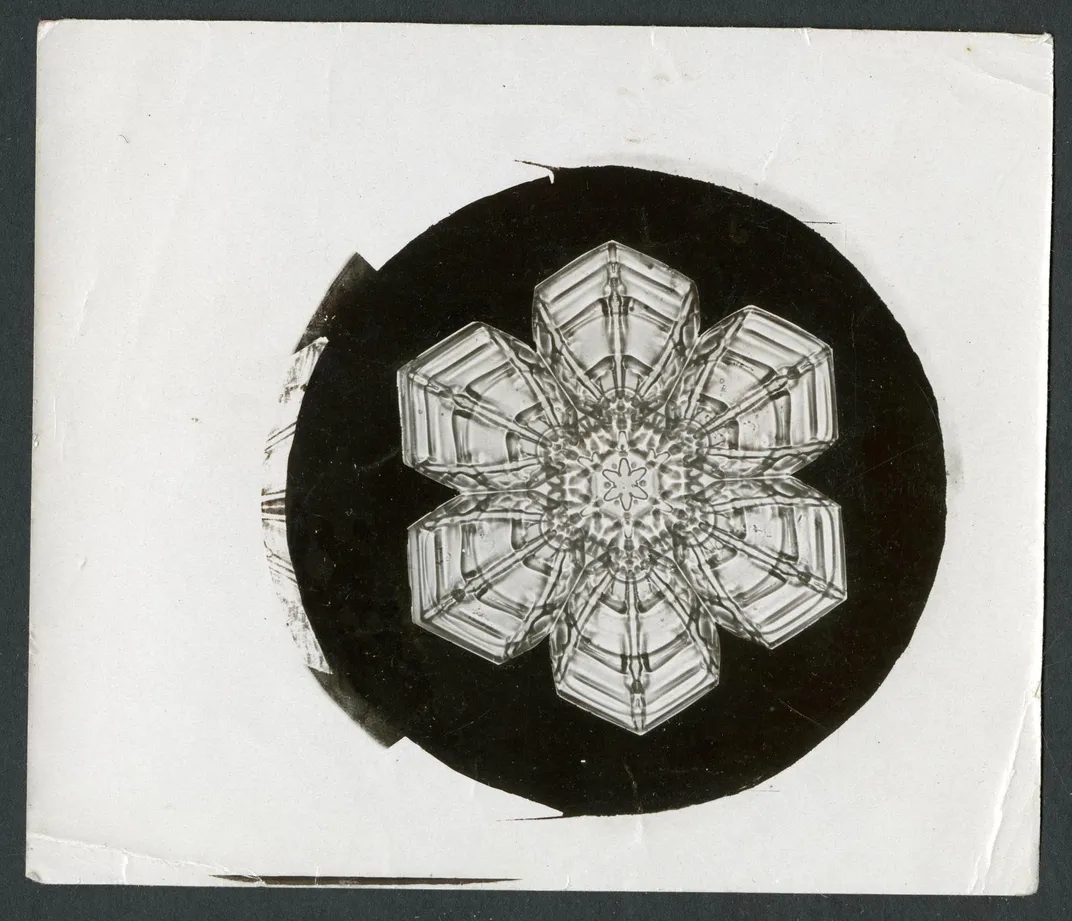

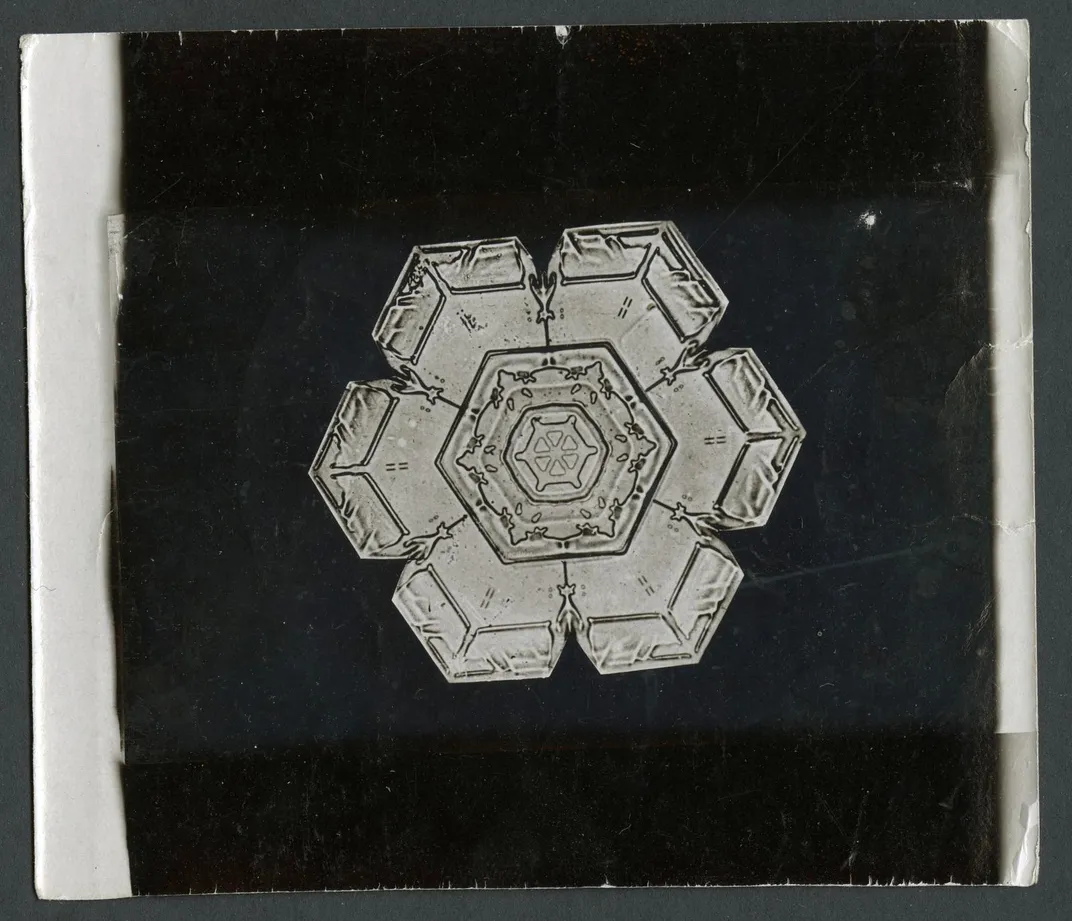

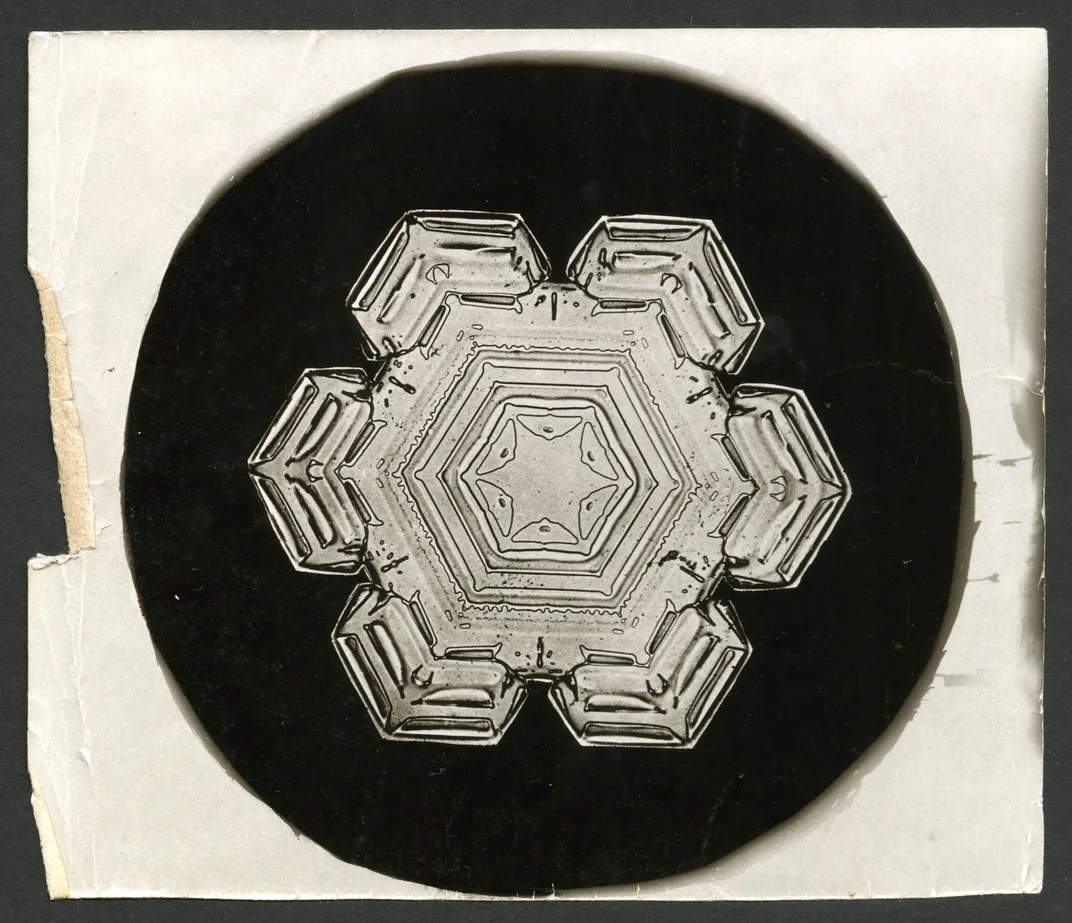

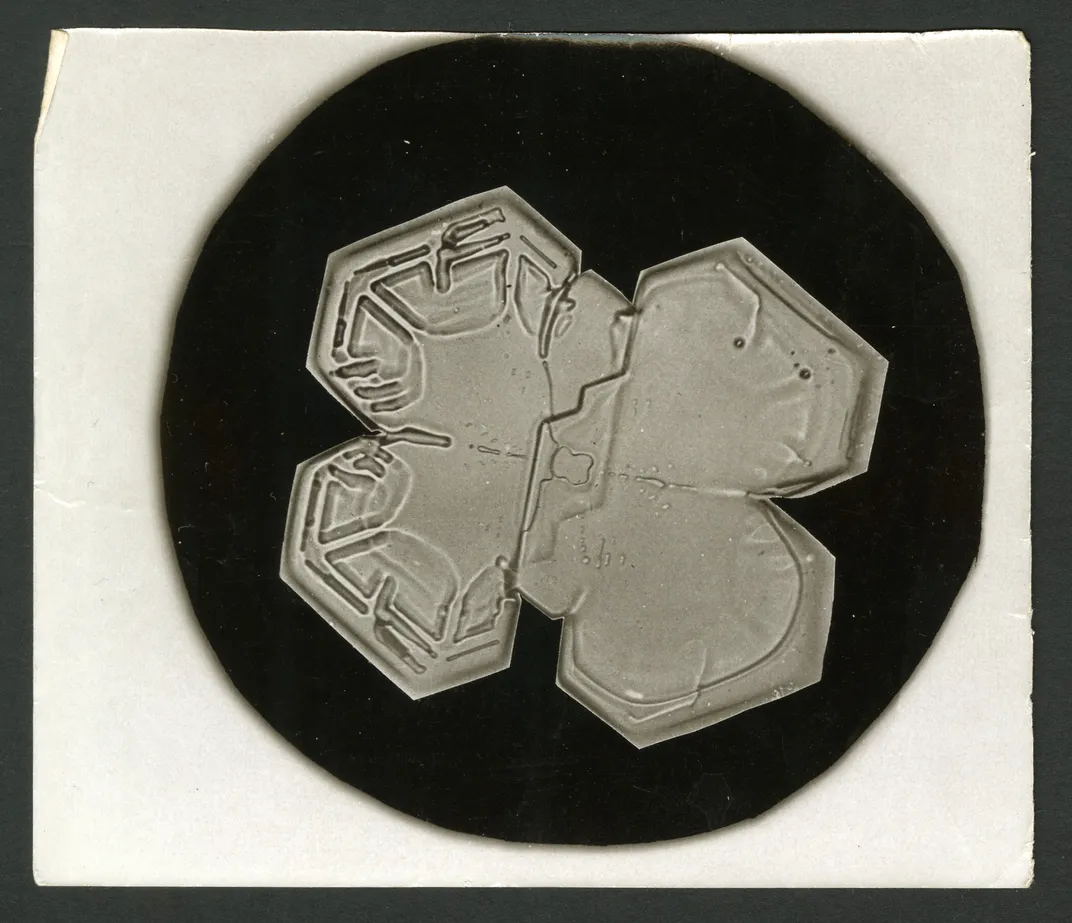

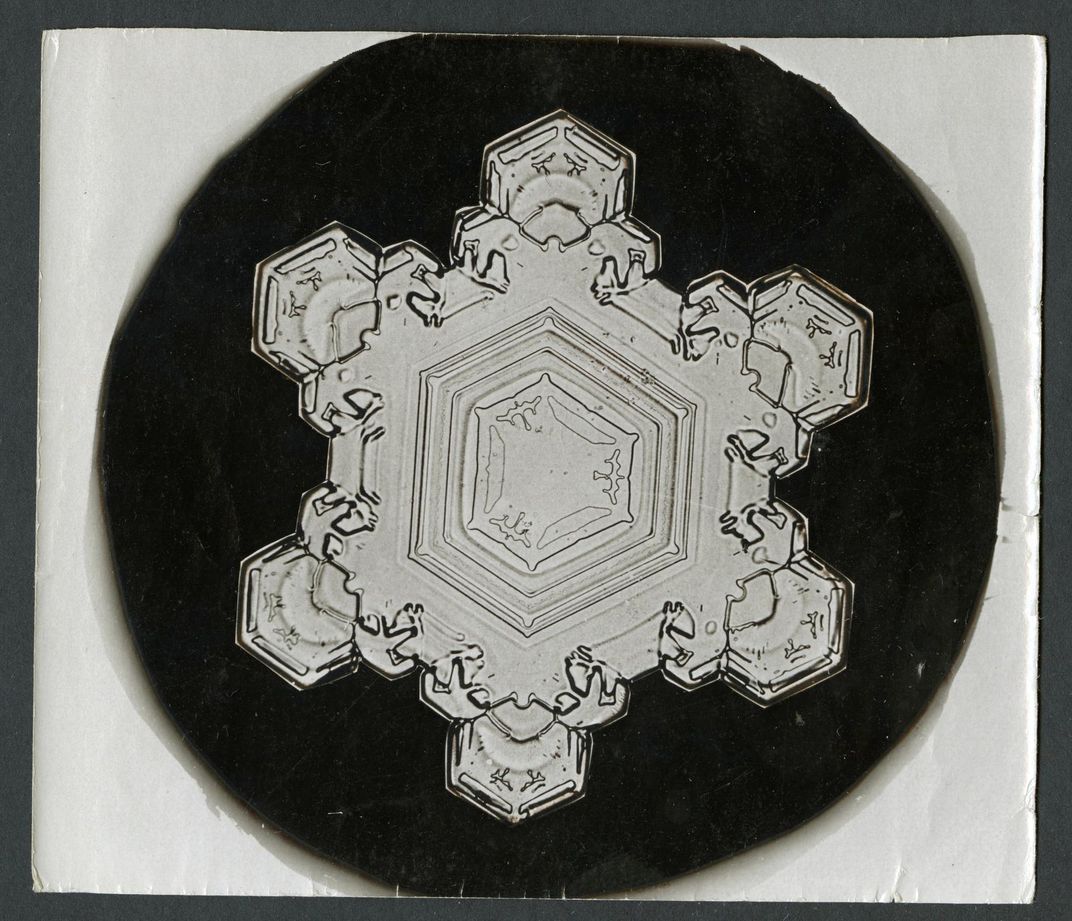

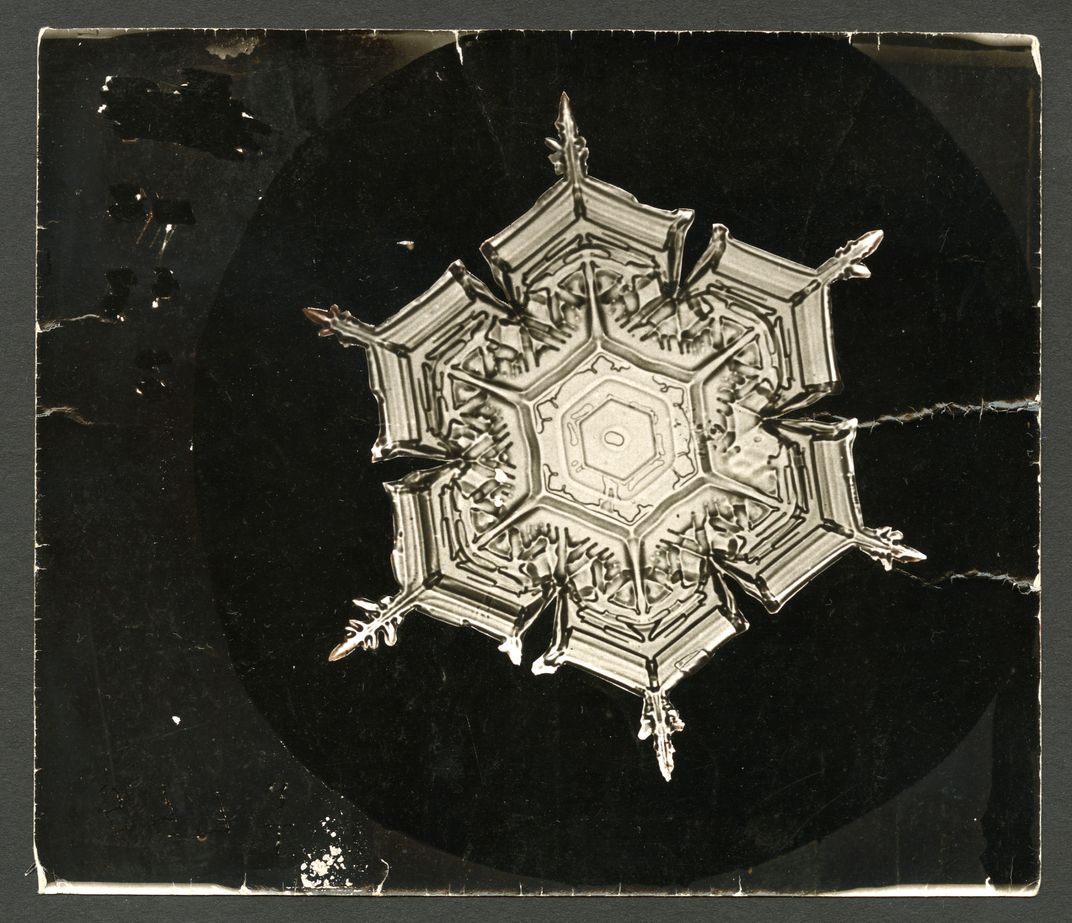

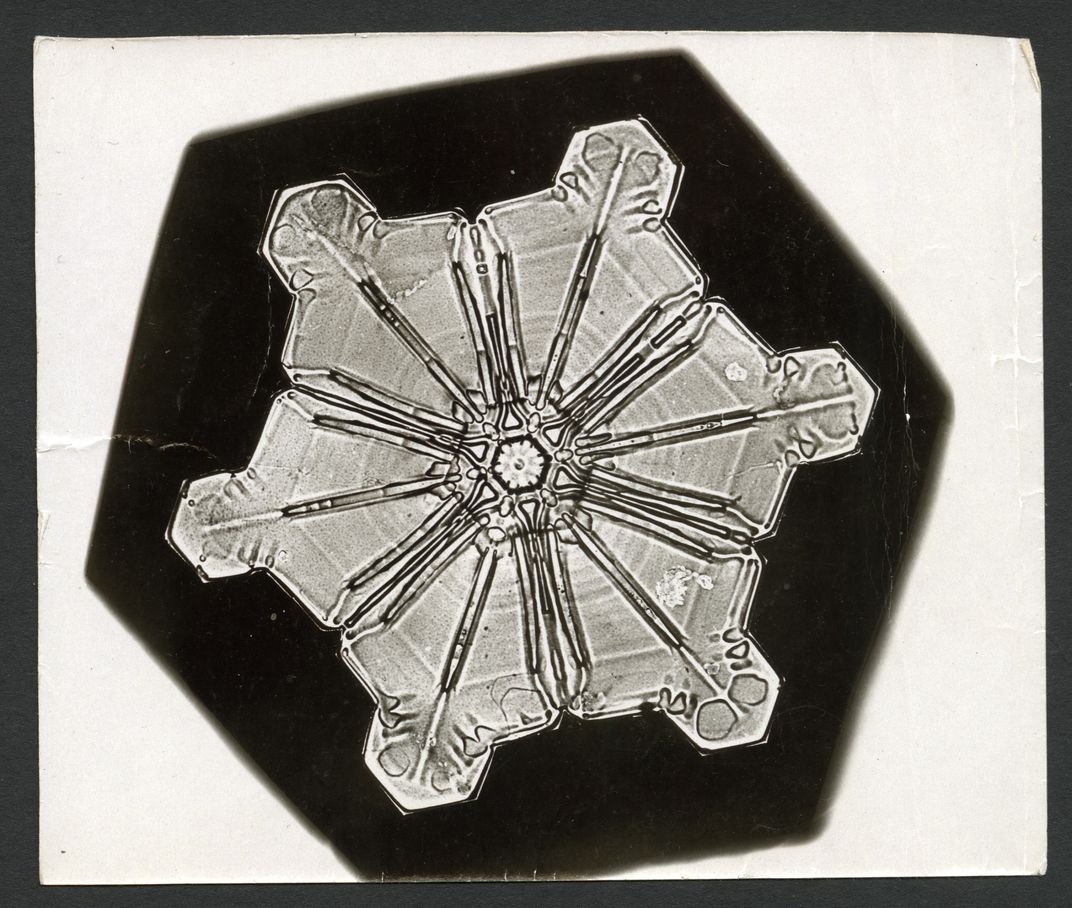

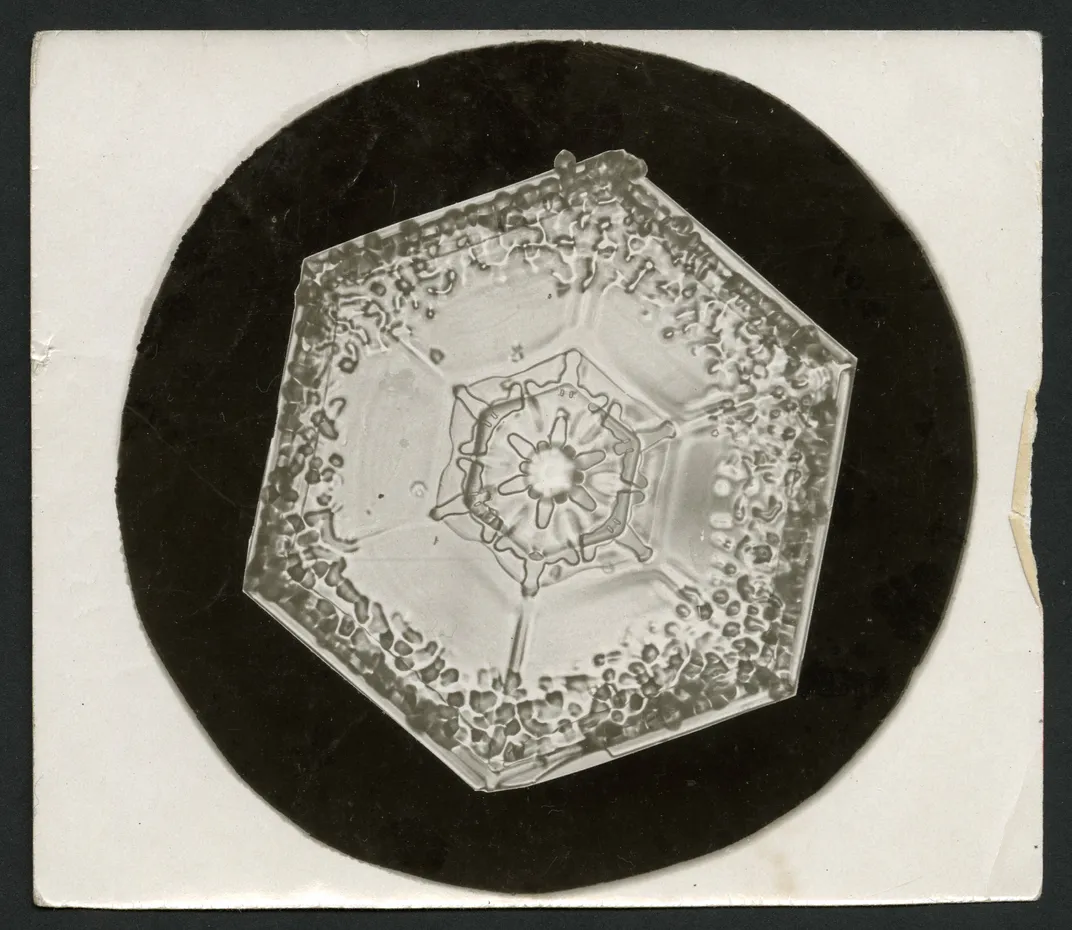

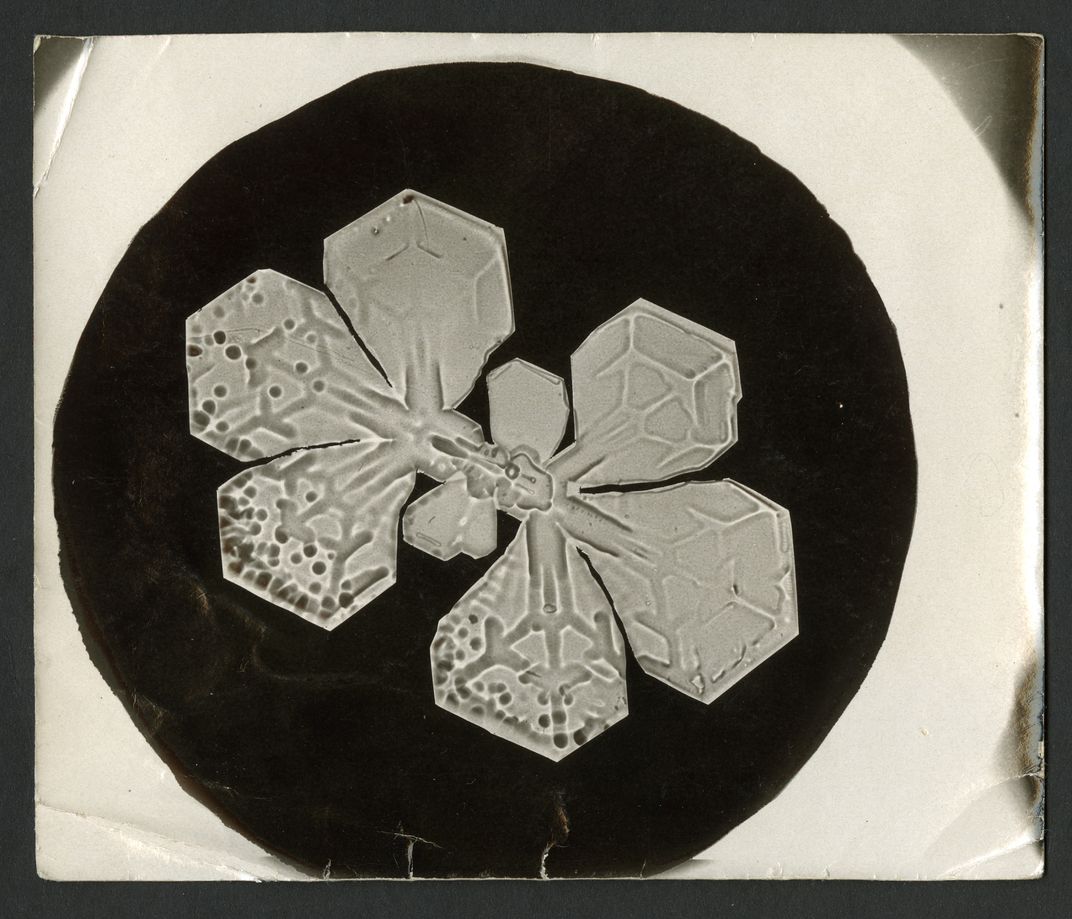

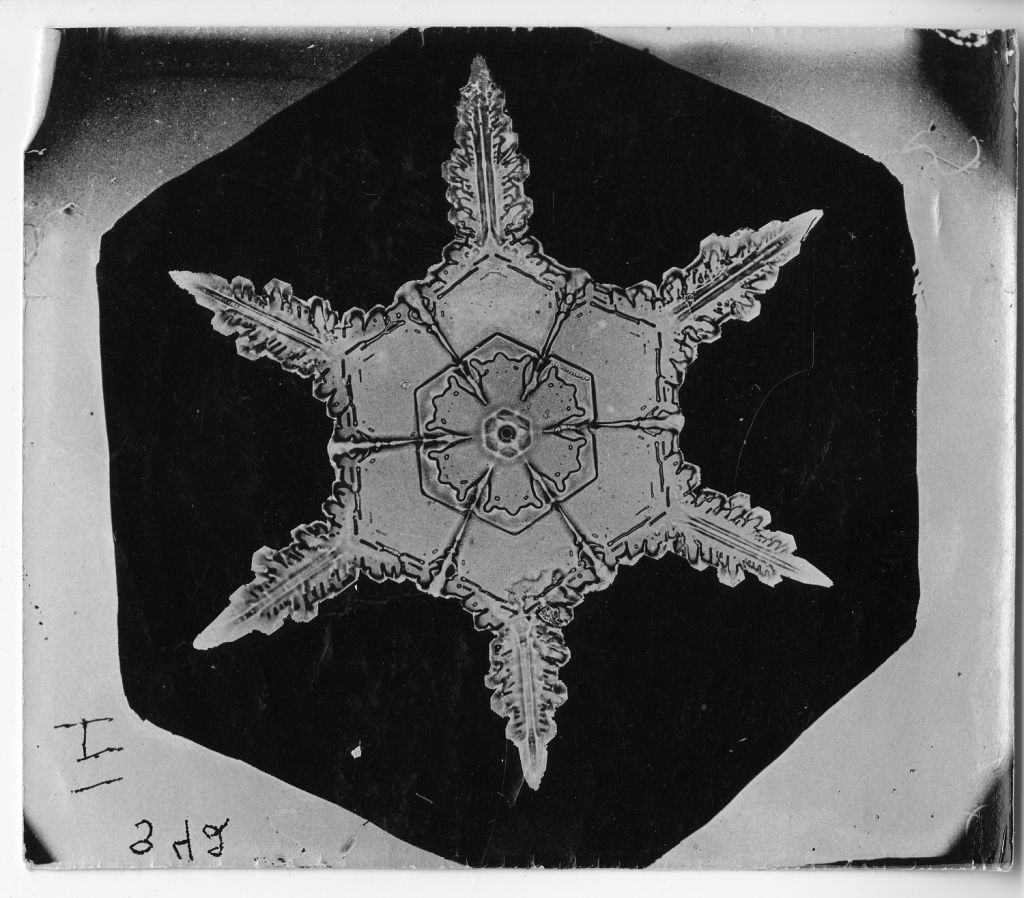

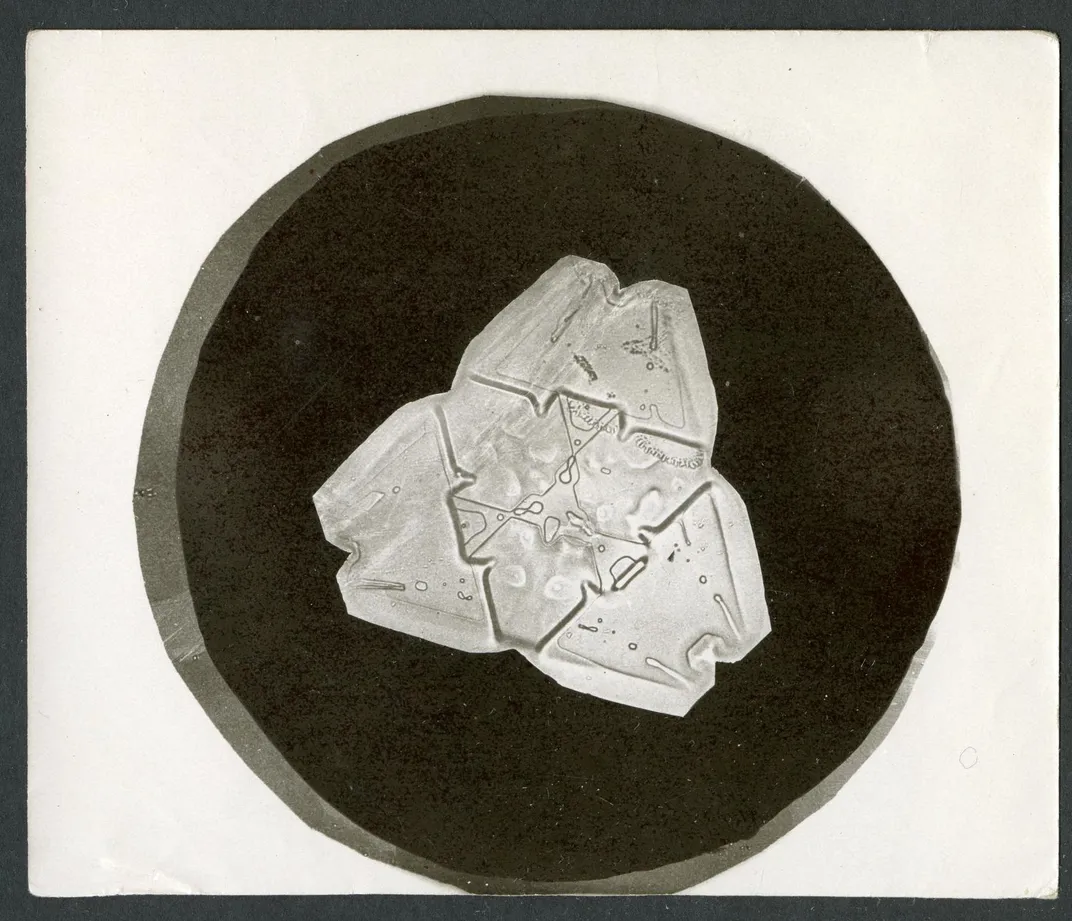

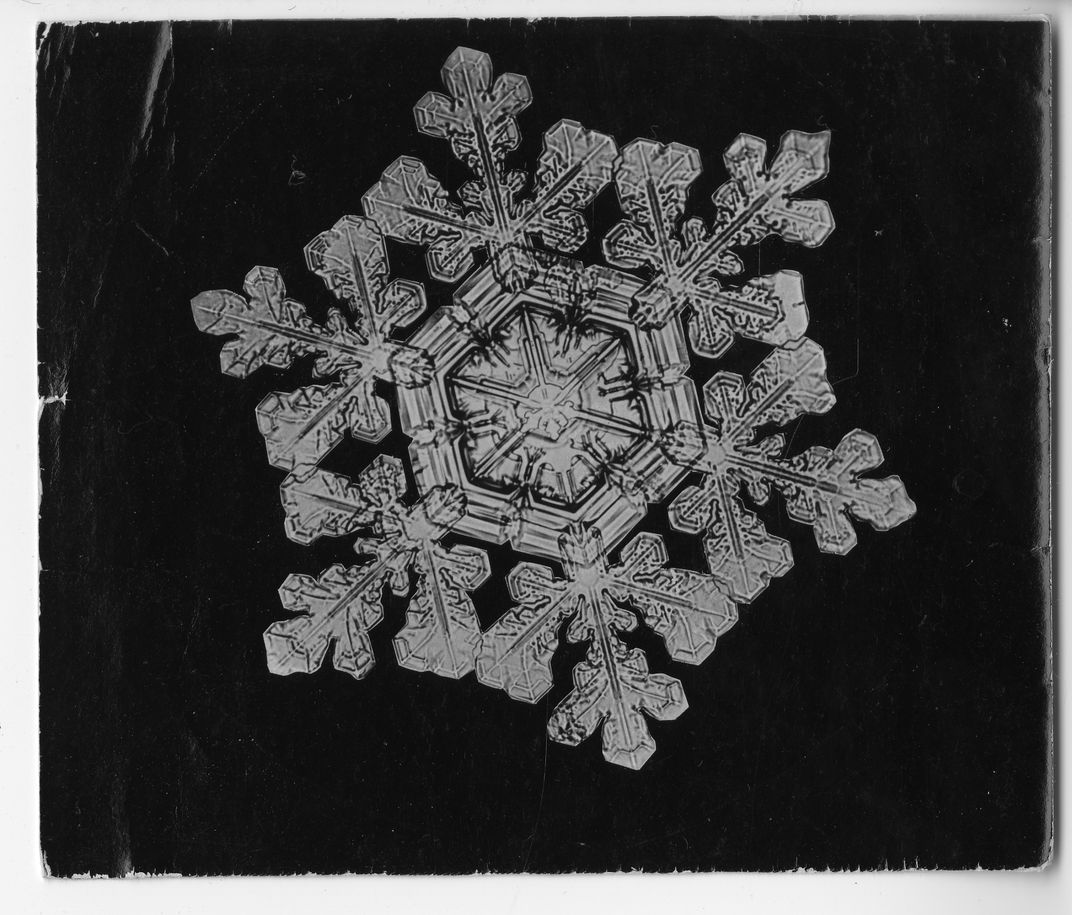

Vermont farmers struggle against short growing seasons and long, deep winters. Beginning in the early 1880s, Bentley made use of what might have been fallow days by devising a mechanism that combined a microscope with a view camera. Using light-sensitive glass plates not unlike those that had recorded Civil War battlefields, he learned how to make extraordinarily sophisticated "portraits" of individual snow crystals.

As Eadweard Muybridge had used the camera to elucidate the previously misunderstood mechanics of a galloping horse, Bentley captured the likenesses of tiny objects both fragile and evanescent. Isolating individual crystals itself posed a daunting challenge—there may be 200 of them in a large snowflake. And keeping the crystals frozen and unspoiled required Bentley to work outside, using balky equipment. Bentley seemed willing to pursue his arduous work—over the years he made pictures of thousands of snow crystals—not with any hope for financial gain but simply for the joy of discovery. Nicknamed Snowflake by his neighbors, he claimed his pictures were "evidence of God's wonderful plan" and considered the endlessly varied crystals "miracles of beauty."

In 1904, Bentley approached the Smithsonian with nearly 20 years of photographs and a manuscript describing his methods and findings. But geology curator George Merrill rejected the submission as "unscientific." (Eventually, the U.S. Weather Bureau published the manuscript and many of the photographs.) Avowing that "it seemed a shame" not to share the wonders he had recorded, Bentley sold many of his glass plates to schools and colleges for 5 cents apiece. He never copyrighted his work.

Bentley's efforts to document the artistry of winter garnered him attention as he grew older. He published an article in National Geographic. Finally, in 1931, he collaborated with meteorologist William J. Humphreys on a book, Snow Crystals, illustrated with 2,500 of Snowflake's snowflakes.

Bentley's long, frigid labors culminated just in the nick of time. The man who revealed the glittering secret of every white Christmas died that same year on December 23 at his Jericho farm. The weather forecast for the day promised occasional showers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)