Evolution on Trial

Eighty years after a Dayton, Tennessee, jury found John Scopes guilty of teaching evolution, the citizens of “Monkeytown” still say Darwin’s for the birds

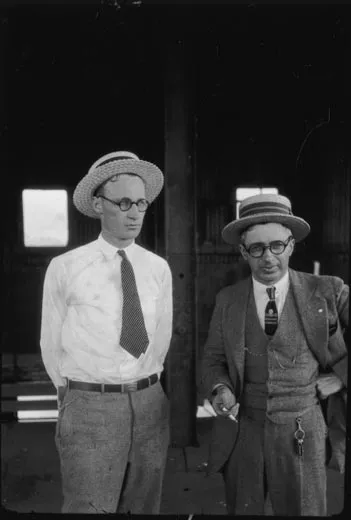

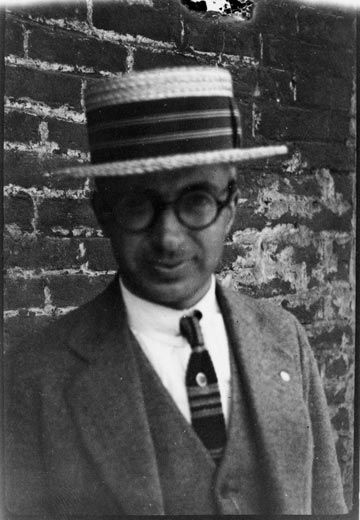

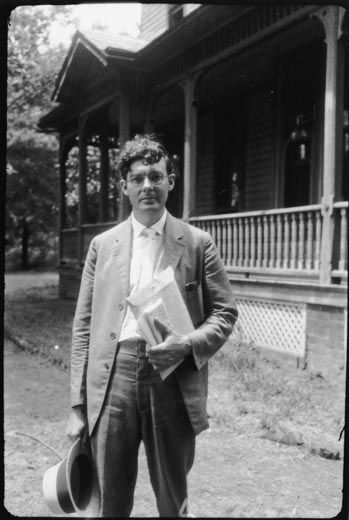

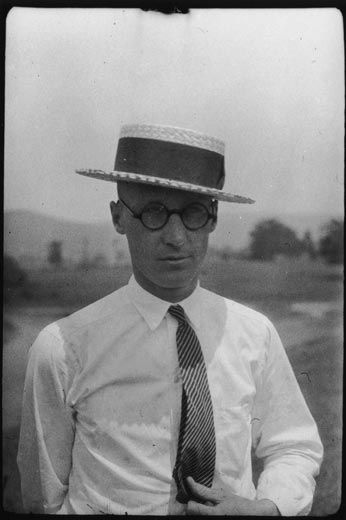

In the summer of 1925, when William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow clashed over the teaching of evolution in Dayton, Tennessee, the Scopes trial was depicted in newspapers across the country as a titanic struggle. Bryan, a three-time presidential candidate and the silver-tongued champion of creationism, described the clash of views as "a duel to the death." Darrow, the deceptively folksy lawyer who defended labor unions and fought racial injustice, warned that nothing less than civilization itself was on trial. The site of their showdown was so obscure the St. Louis Post-Dispatch had to inquire, "Why Dayton, of all places?"

It's still a good question. Influenced in no small part by the popular play and movie Inherit the Wind, most people think Dayton ended up in the spotlight because a 24-year-old science teacher named John Scopes was hauled into court there by Bible-thumping fanatics for telling his high-school students that humans and primates shared a common ancestry. In fact, the trial took place in Dayton because of a stunt. Tennessee had recently passed a law that made teaching evolution illegal. After the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced it would defend anyone who challenged the statute, it occurred to several Dayton businessmen that finding a volunteer to take up the offer might be a good way to put their moribund little town on the map.

Judge James "Jimmy" McKenzie, whose grandfather Ben, and uncle, Gordon, helped prosecute Scopes, says, the trial "gave Dayton a black eye." But in spite of all the hoopla and history associated with it, he notes wryly, "the case didn't solve anything." "As a result of the Scopes trial, evolution largely disappeared in public school science classrooms [until the late 1950s]," says historian Edward J. Larson, a professor at the University of Georgia and author of Summer for the Gods, a Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the trial and its aftermath. Larson acknowledges that there is "more mandated teaching of evolution now than ever before." But that doesn't necessarily translate into actual teaching.

Today, one thing about Dayton has not changed and probably never will: its bedrock fundamentalism. Even now, it's hard to find a teacher who goes along with Darwin. "We all basically believe in the God of creation," says the head of the high-school science department.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kemper_HighRes_2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kemper_HighRes_2.png)