Dinosaur Bones Shimmering With Opal Reveal a New Species in Australia

A discovery in an Australian opal mine remained unexamined for three decades—it turned out to be the most complete opalized dinosaur skeleton in the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/a9/7da9c723-f1d5-4a7c-ae1d-9f6f95243cee/picture1.png)

Three decades ago, opal miner Bob Foster was getting frustrated while digging around in his mining field just outside of Lightning Ridge, a dust-swept town in outback New South Wales. Foster and his family spent hours a day searching for a glimmer of rainbow-shaded gems embedded in the rocks 40 feet underground. But all they found were a bunch of dinosaur bones.

“We would see these things that looked like horses,” says Foster. “Then we would just smash them up to see if there were any opals inside.”

But there was something strange about the growing collection of bones accumulating in Foster’s living room. Piling the bones into two suitcases, Foster took a 450-mile train ride to the Australian Museum in Sydney. When museum curator Alex Ritchie examined Foster’s bone collection dumped on his desk, he recognized them for what they were and knew immediately that an expedition to the opal miners site, called the “Sheepyard,” was in order.

The excavation team wasn’t disappointed. In 1984, they hauled out the most complete dinosaur skeleton ever found in New South Wales. The bones, which were encrusted with sparkling opal, were taken back to the Australian Museum for public display. Two decades later, Foster took the fossils back and donated them to the Australian Opal Centre in Lightning Ridge.

While the stunning fossils had been seen by plenty of museum visitors, no one had formally studied them. Now, researchers have finally taken a closer look at what was uncovered near Foster’s family home 35 years ago. The findings, published today in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, reveal a new species, the first fossil evidence of a dinosaur herd in Australia, and the most complete opalized dinosaur skeleton in the world.

“This is unheard of in Australia,” says Phil Bell, the study’s lead author and paleontologist at the University of New England in Armidale, New South Wales. “There were around 60 odd bones in the entire collection, which is a remarkable number for an Australian dinosaur.”

The glittering remains, encrusted with opal, represent the newly described species Fostoria dhimbangunmal. The species is the youngest Australian member of the iguanodontian dinosaurs, a plant-eating group that had a horse-shaped skull and a similar build to the kangaroo. The United Kingdom’s Iguanodon and Australia’s Muttaburrasaurus are among Fostoria’s more famous cousins. The name of the new dinosaur is a nod to its original discoverer, with ‘dhimbangunmal’ meaning ‘sheep yard’ in the Yuwaalaraay, Yuwaalayaay and Gamilaraay languages of the Indigenous people living in the area near Lightening Ridge.

Compared to China and North America, Australia is hardly regarded as a prehistoric hotspot for dinosaur hunters. Over the past century, just 10 species of dinosaur have been discovered in Australia, including the three-toed Australovenator and the long-necked Wintonotitan and Diamantinasaurus, which were discovered in Queensland last year. Lightning Ridge, one of the richest sources of opal in the world, is the only site in New South Wales where dinosaur bones have been found. Since the 1930s, opal miners like Foster have dug up 100-million-year-old bone and tooth fragments by accident. One such discovery, an opalized jawbone discovered by Bell in late 2018, turned out to be a new dog-sized dinosaur species called Weewarrasaurus pobeni.

“The discovery of dinosaur groups unique to the southern hemisphere suggests that our current understanding of dinosaur evolution is incomplete,” says Ralph Molnar, a paleontologist at Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. “Australian dinosaurs are globally important, and as more discoveries are made, they will play an increasingly significant role in our understanding of that time.”

When Bell first laid eyes on the pile of fragments, he assumed that they all came from one animal. Hours of CT scanning at the local radiology clinic revealed large fragments of backbone, skull, limb, foot and hip. But something about the massive collection didn’t add up. “There were all these duplicates, and we couldn’t stick the bones together to make a full skeleton,” Bell says. “What really hit it off was when we realized that we had four shoulder blades, all of different sizes.”

There was only one explanation: Each shoulder blade belonged to a separate individual. The largest shoulder blade likely belonged to an adult, while the three smaller pieces were from juvenile dinosaurs. The four skeleton remains suggest that Fostoria, which lacked big claws and sharp teeth, stuck together in herds or family groups to protect themselves from predators. Aside from trackways of dinosaur footprints in Queensland and Western Australia, there had been no other fossil evidence of dinosaur herds found in the country until now. Fostoria’s flat teeth indicate that the animals fed on plants and foraged on two legs. Bell says that the 16-foot dinosaurs were “quite plain to look at, with no extravagant horns or crests.”

The land these dinosaurs roamed around 100 million years ago in the mid-Cretaceous was much different than the dry, shrubby scenery of Lightning Ridge today. While Australia was part of Gondwanaland—the supercontinent that included South America, Africa, Antarctica and India—the historic mining town was located 60 degrees south of where it is today, making its climate more mild than current temperatures. The parched land in the area was once dotted with rivers, lagoons and floodplains that cut through lush vegetation.

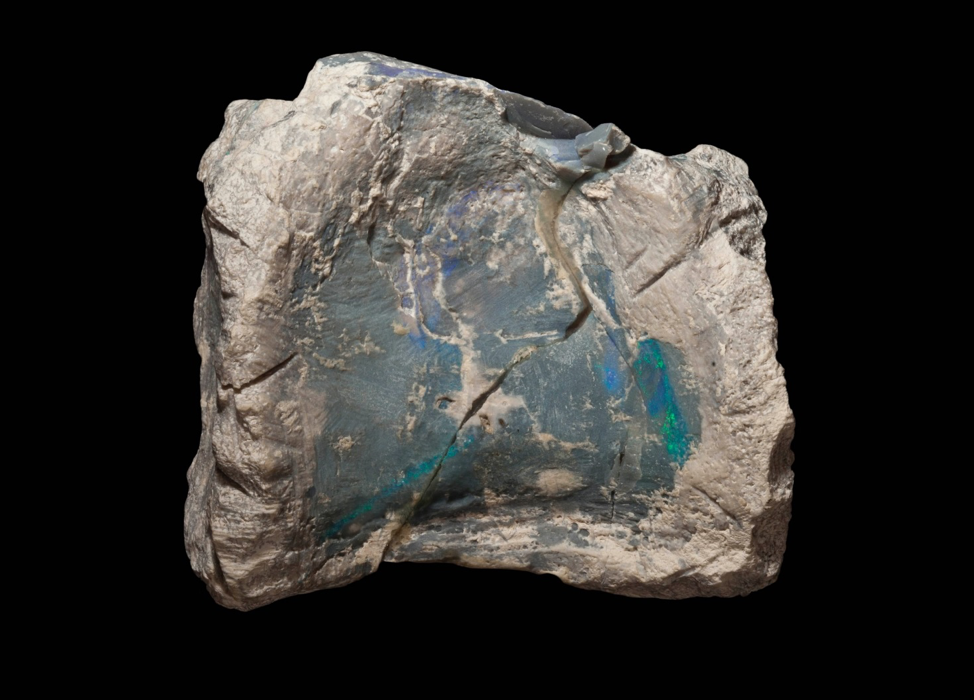

The layers of sediment that buried ancient plants and animals were rich in silica, a building-block of sand. Over time, this silica seeped into cracks and holes in fossils, eventually forming opal in dead animals such as snails, fish, turtles, bird and mammals. While Fostoria’s appearance may have been “plain” while it was alive, the opalized fossils it left behind now shimmer with streaks of green and deep blue.

Bell hopes the findings shine a spotlight on Australia’s dinosaur diversity, which will help paleontologists uncover clues about the Gondwanan environment and the plants and animals that inhabited the prehistoric continent. While extensive research on South America’s paleontological history has revealed insights about the western half of Gondwanaland, the eastern side continues to be shrouded in mystery. With Antarctica blanketed in ice and most of the New Zealand continent underwater, sites like Lightning Ridge are key to unravelling the southern hemisphere’s ancient past.

“Australia absolutely did have dinosaurs, and they were totally different and exciting,” Bell says. “They are just not in text books, but we’re going to change that.”