Bizarre Blue Shark Nursery Found in the North Atlantic

Rather than emerging in protected coves, baby blue sharks spend their first years in a big patch of open ocean

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/da/9edaf3c9-65f2-4fe2-bdd6-b2674263bab1/shark.jpg)

Blue sharks, like many sea creatures, are nomads, and their habits over a lifetime have been cloaked in mystery. Now, for the first time, researchers from Portugal and the US think they know where some baby blue sharks come from—and where they eventually go.

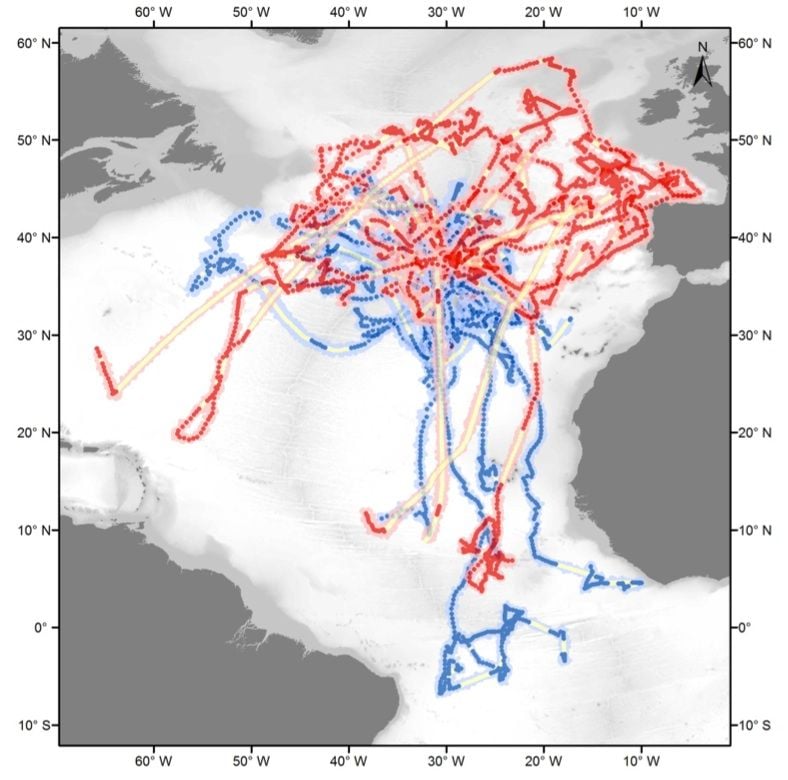

The team tracked dozens of blue sharks for an unprecedented 952 days, revealing that the globetrotting predators seem to start their lives in a peculiar nursery—a large patch of open ocean. The discovery may prove vital in efforts to protect the species from deadly encounters with longline fisheries, which inadvertently snare around 20 million blue sharks each year.

Blue sharks live in oceans around the world and can travel unconstrained over large swaths of territory. For the new study, Frederic Vandeperre at the University of the Azores in Portugal and his colleagues decided to focus on the waters around the Azores islands in the North Atlantic. Fishing boats frequently catch both young and mature sharks in that area, an early clue that there might be a nursery and mating ground nearby.

The scientists trapped 37 blue sharks ranging in age from young juveniles to adults and outfitted them with satellite transmitters. They released the sharks and then waited for the data to arrive. As months rolled into years, an interesting pattern emerged. Within the first two years of life, the researchers report in the journal PLOS ONE, the sharks spent most of their time in a patch of the North Atlantic. Most shark species establish nurseries in protected bays or other sheltering areas. The notion that blue sharks grow up completely out in the open suggests that protection from predators is not a motivating factor. But figuring out what advantages, if any, that particular spot provides will require further study.

Tracking data also showed that after a couple years, males and females went their separate ways. Females generally took off on seasonal, looping migrations between the nursery and more northern waters, while males mostly headed south. Once the females hit maturity at about four years old, however, they turned their attention to the warmer tropics, where many of the males had headed months before. The researchers think this strategy might help young females avoid aggressive males looking to mate until they themselves are mature enough to safely engage in those activities. The team also found that, throughout their lives, both males and females regularly returned to the nursery site, likely to mate and deliver young.

Once the sharks ventured out the nursery, many of them covered an impressive distance, the researchers added. One female traveled more than 17,000 miles over the 952-day study period, and one male made it into the southern hemisphere.

Blue sharks are currently listed as “near threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. And while the IUCN says that there has been relatively little population decline of blue sharks, the group’s experts add: “There is concern over the removal of such large numbers of this likely keystone predator from the oceanic ecosystem.”

One way of ensuring the species does not fall into the “threatened” category or worse would be to acknowledge the presence of the Atlantic nursery ground, the PLOS ONE authors write. Given the high number of sharks that fishermen report accidentally capturing in that area each year, some seasonal protection measures may be a boon to the blue shark.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)