Ancient Bees Were Voracious Snackers on Their Pollen-Gathering Treks

Fossils from Germany could help researchers better understand modern bee eating habits and better protect the beloved pollinators

:focal(1985x875:1986x876)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/68/c568389f-6355-4e08-b292-15ab1904c60f/42-67139928.jpg)

When scientists want to know where a honeybee has traveled, they usually just look in its pollen basket. That's the dense region of sticky hairs on their legs where bees shove pollen grains, compacting them until they have enough to take home to feed their offspring.

“Sometimes [the basket] gets into absurd proportions,” says David Grimaldi, an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History. “You see them with these huge balls of pollen, and they can hardly fly.”

Baby bees eat the pollen, but the adults prefer nectar. Adult bees fly long distances and use up lots of energy, so they have to eat constantly. Now, analysis of pollen collected from fossilized bees suggests that the insects of yore were dining on nectar from flowers beyond those targeted for pollen collection.

The findings represent the earliest evidence of a dual-collection strategy in bees, where they feed their offspring pollen from one type of plant but are eating from all kinds of plants themselves, says study co-author Conrad Labandeira, a paleobiologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. The result could help ecologists better understand what modern bees are eating so we can protect those food sources.

“We're really concerned about modern-day bees’ health and what flowers they visit,” says Hannah Burrack, an entomologist at North Carolina State University who was not involved in the research. “This [study] is important for preserving and assessing the health of the bees.”

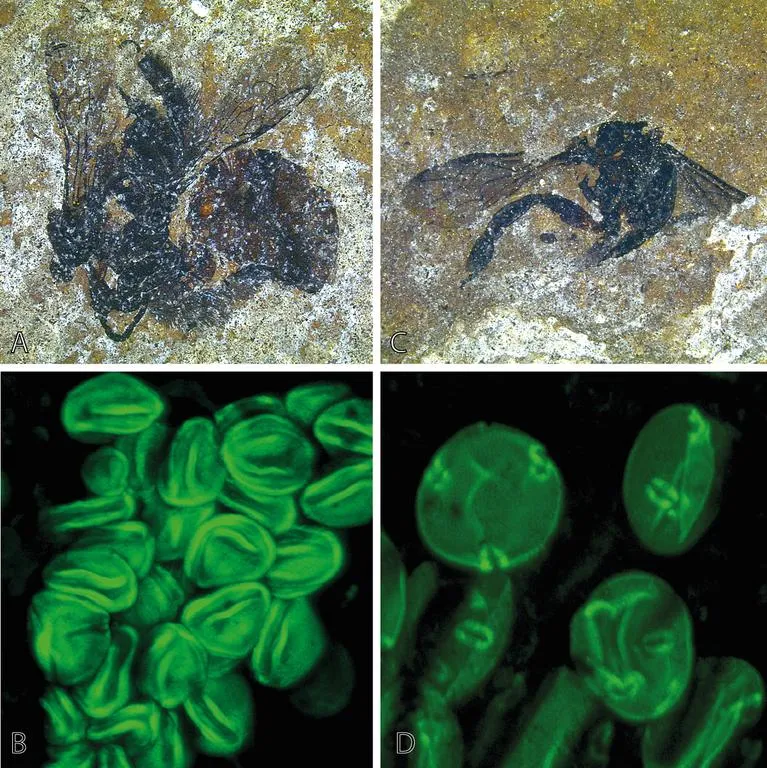

For the study, published this week in Current Biology, Labandeira and a team of international colleagues looked at individual grains of pollen attached to six ancient bee species from the now-extinct tribe Electrapini. The species are between 44 million and 48 million years old and were found lodged in oil shale deposits outside of Frankfurt, Germany.

The scientists used tiny pieces of tape to lift pollen off the ancient bees’ bodies and then studied it under a microscope. They found that the pollen on their legs mainly came from the same source, while the grains on their bodies were much more diverse.

Matching the pollen to ancient plants, the team found that the grains being collected for transport back to the hive came mainly from the blossoms of evergreen bushes, which all had the same basic flower structure. These flowers deposited pollen on the bees' bodies in places where it was easy for them to brush the grains back onto their legs, thus maximizing their harvest.

By contrast, pollen still stuck to their bodies came from all sorts of flowers, left accidentally when the bees made indiscriminant pit stops along the way.

Modern bees likely follow similar patterns, and finding out where they are going could be crucial to their survival. Previous work suggests that bees have changed very little in the past 48 million years, Labandeira says. This means they are slow to evolve and have become very well adapted to certain conditions, so any rapid changes to an ecosystem, like introducing pesticides or extreme temperature increases, could cause an entire species to go extinct.

“We tend to think that things evolve in thousands of years, but we're talking tens of millions of years,” Grimaldi says. “When you destroy habitats and then to try to [rebuild them], it might never be possible because of how long it’s taken to establish in evolutionary time,” he adds.

And this new work suggests that any scientist just looking at a bee’s pollen basket is missing out on a big part of the insect’s travel patterns, Burrack says. In the future, agriculturalists should study both the bee's legs and their bodies to see which flowers and plants the insects are visiting. The resulting information could help save modern-day honeybees, which are important pollinators for many of the world’s crops.

“This study is so important, because bees are so important,” Grimaldi says. “No other group of insects has the ecological significance of bees. They’re so essential to agriculture.”