The Woman Who Made a Device to Help Disabled Veterans Feed Themselves—and Gave It Away for Free

World War II nurse Bessie Blount went on to become an inventor and forensic handwriting expert

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/d7/5ed70a87-54b4-4c7a-848b-a9e173c5b63f/bessieblount_illustration.jpg)

In 1952, Bessie Blount boarded a plane from New York to France to give away her life’s work. The 38-year-old inventor planned to hand over to the French military, free of charge, an extraordinary technology that would change lives for disabled veterans of the Second World War: an automatic feeding device. To use it, a person only needed to bite down on a switch, which would deliver a mouthful of food through a spoon-shaped tube.

When asked nearly 60 years later why she had simply given away such a valuable invention, she made it clear that her aim wasn’t money or notoriety—it was making a point about the abilities and contributions of black women. “Forget me,” she said. “It’s what we have contributed to humanity—that as a black female we can do more than nurse their babies and clean their toilets.”

Forget her, however, we cannot. For the second half of her answer has far eclipsed the first: the innovations Blount pioneered on behalf of humanity have marked her indelibly in the historical record. In her long life—she lived to be 95 years old—Blount was a lot of things: nurse, physical therapist, even forensic handwriting expert. But more than anything else, she was an inventor. She dreamed up assistive technologies for people with disabilities, and she constantly reinvented herself, teaching herself how to build new doors when others were closed to her.

Blount was born in Hickory, Virginia in 1914 to George Woodward and Mary Elizabeth Griffin, who had set deep roots in Norfolk. Though a generation apart, both Mary and Bessie attended the same one-room schoolhouse and chapel, Diggs Chapel Elementary School. The school-chapel’s miniscule size belied its significance to the community: it was established at the end of the Civil War to educate the children of free black people, former slaves and Native Americans.

It was in this one-room schoolhouse that Blount first learned how to remake herself. She was born left-handed, and she recalled in multiple interviews with journalists how her teacher, Carrie Nimmo, hit her across the knuckles for writing with her left hand. She responded to the teacher’s demands by teaching herself how to write with both hands, her feet—even her teeth.

After Blount finished the sixth grade, she took her education upon herself. She had no choice; there were no schools in the area that offered higher education to black children. Eventually, she qualified for college acceptance at Union Junior College in Cranford, New Jersey and nursing training at Community Kennedy Memorial Hospital in Newark, the only hospital owned and run by black people in New Jersey. She went on to take post-graduate courses at Panzer College of Physical Education and Hygiene, now part of Montclair State University. She ultimately became a licensed physiotherapist, and took up a post at the Bronx Hospital in New York City around 1943.

In 1941, while Blount was still pursuing her medical education, the United States formally entered World War II. She responded by putting her nursing skills to use as a volunteer with the Red Cross’s Gray Ladies at Base 81, which served servicemen and veterans in the metro New York and northern New Jersey area. Named for the color of their uniforms, the Gray Ladies were meant to be a non-medical group of volunteers who provided hospitality-based services to military hospitals. In actuality, much of their actual hands-on work included facility management, psychiatric care and occupational therapy.

Blount’s work with the Gray Ladies brought her in contact with hundreds of injured soldiers overwhelming veteran’s hospitals. “About 14,000 in the army experienced amputation, and survived amputation,” war and disability historian Audra Jennings tells Smithsonian.com. With upper limb amputation, many soldiers lost the ability to write with their hands. So Blount pushed them to learn another way, just as she had many years before—with their feet and teeth. Some even learned to read Braille with their feet.

In what little spare time she had, Blount enjoyed working with artists and photographers, posing for medical sketches and photos. Through her work with artists, Blount herself learned how to draw. “This enabled me to design many devices for handicapped persons,” she recalled in a 1948 interview with the newspaper Afro-American. “After coming in contact with paralyzed cases known as diplegia and quadriplegia (blind paralysis), I decided to make this my life’s work.”

The inspiration for a feeding device came when a physician at the Bronx Hospital told her that the army had been trying to produce a viable self-feeding device but had been unsuccessful. If she really wanted to help disabled veterans, the doctor said, she should figure out a way to help them feed themselves.

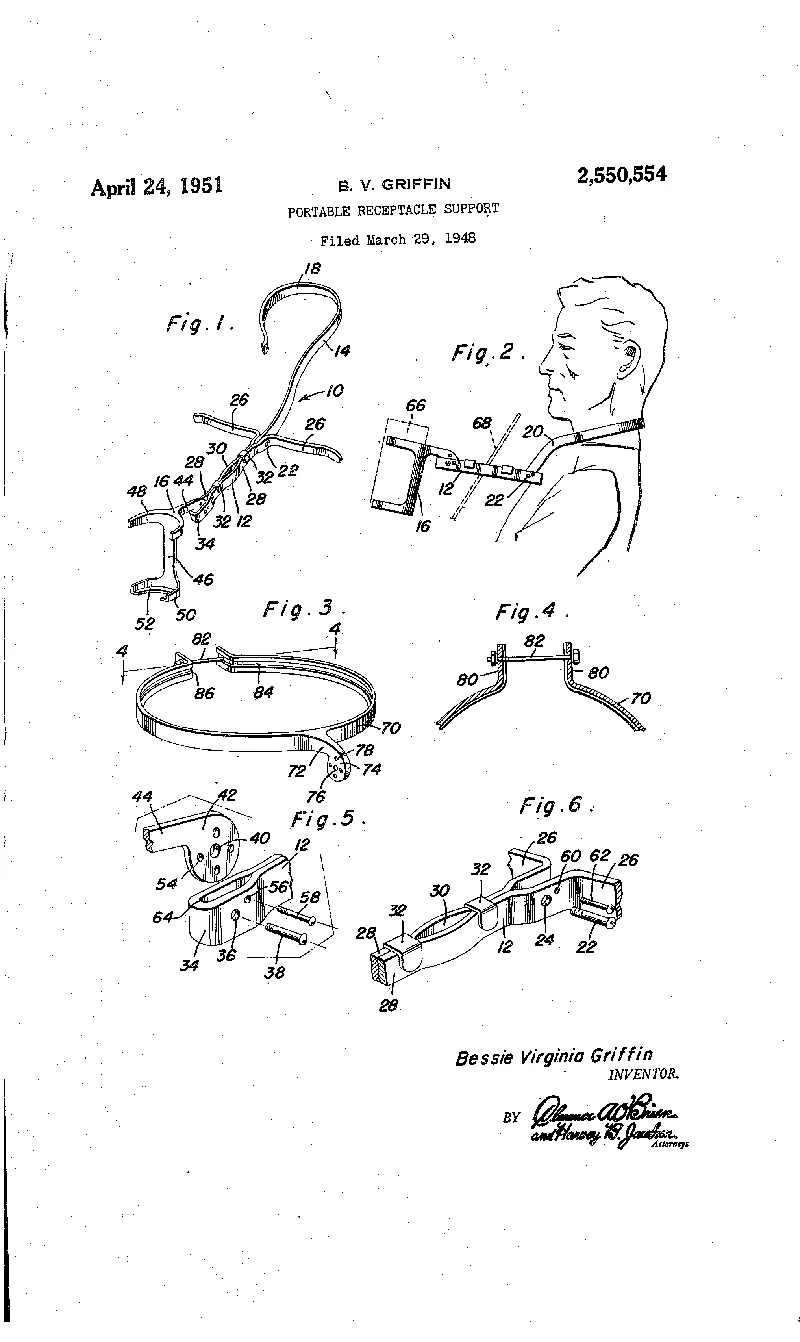

Spurred on, Blount worked for five years to create a device that would do just that. Turning her kitchen into her workshop, she spent ten months designing a device for those who had either underwent upper limb amputation or paralysis. Then, she spent four more years and a total of $3,000 of her own money to build it. Her creation would shut off automatically after each bite, so that the individual could control their own feeding. She also designed and build a non-automatic food receptacle support, for which she received a U.S. patent, that affixed to an individual’s neck and could hold a dish or cup. “I usually worked from 1 a.m. to 4 a.m.,” she told the Afro-American.

By 1948, her device was ready for use. Yet when she presented her completed prototype to the VA, she was stunned by a rejection. For three years, Blount tried to make inroads with the VA, but finally after being permitted a meeting with VA authorities, she was told in a letter from chief director Paul B. Magnuson that the device was not needed and that it was “impractical.”

“It was not surprising to me that the VA did not adopt this new technology,” says Jennings; the VA was largely underprepared to support the number of injured and disabled veterans, and assistive technology just wasn’t there yet. Throughout the war and after, lack of preparation, resource shortages, and lack of action on the federal level to improve conditions for disabled people left veterans and the public with a sense that the VA was not providing veterans with sufficient medical care and rehabilitation. Even the prostheses that the VA provided for amputees were poorly made, often produced for “quantity, not quality,” says Jennings.

Despite the U.S. Army’s disinterest in the device, Blount was successful in finding a Canadian company to manufacture it. Eventually, she found a home for it with the French military. “A colored woman is capable of inventing something for the benefit of mankind,” she said in another interview with the Afro-American after the 1952 signing ceremony in France. This device was indeed groundbreaking: Soon following the ceremony, over 20 new patents for assistive devices for people with disabilities, citing Blount, were filed with the U.S. government.

Blount was not yet done inventing, however. As she continued to teach writing skills to veterans and others with disabilities, she began to pay attention to how handwriting reflected a person’s changing state of physical health. In 1968, Blount published a technical paper on her observations titled “Medical Graphology,” marking her transition into a new career in which she quickly excelled.

After the publication of her paper, she began consulting with the Vineland Police Department, where she applied her observations on handwriting and health to examining handwritten documents to detect forgeries. By 1972, she had become the chief document examiner at the Portsmouth police department; in 1976, she applied for at the FBI. When they turned her down, she again turned her sights overseas, finding a temporary home for her talents at Scotland Yard. In 1977, at 63 years old, she began training in the Document Division of the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory, making her the first black woman to do so.

When Blount returned to the states, she went into business for herself. She continued to work with police departments as an expert handwriting consultant and was active in law enforcement organizations like the International Association of Forensic Sciences and the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives. She offered her expertise in handwriting to museums and historians by reading, interpreting and determining the authenticity of historical documents, including Native American treaties and papers relating to the slave trade and the Civil War.

In 2008, Blount returned to that one-room schoolhouse where it all began. She found nothing left of it but some burned down ruins. Given how much history the site held—both her own and that of black children after the Civil War—Blount had planned to build a library and museum. “There's no reason these things should be lost from history,” she said. Unfortunately, before she could see her plans come to fruition, she died in 2009—but her memory lives on in her remarkable life story, her innovative patent designs and the descendants of her signature invention.