Upending the Narrative of the Great Man of History

The Voice of Witness project spearheaded by Dave Eggers and Mimi Lok gives the victims of crisis a megaphone

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Eggers-ingenuity-collage631.jpg)

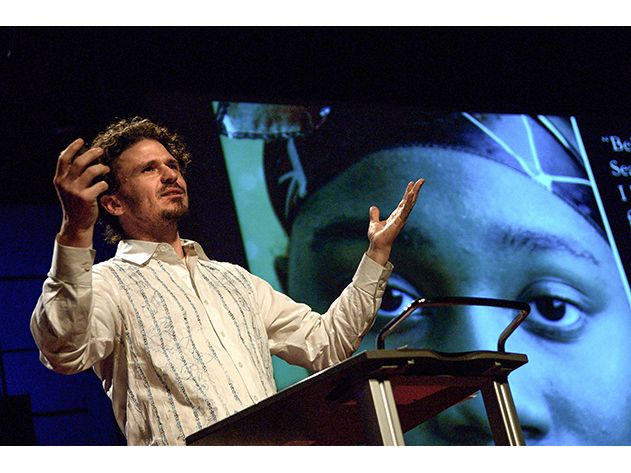

The idea first occurred to Dave Eggers in Marial Bai, a village in southern Sudan. People who’d fled during a decades-long civil war had cautiously started to return home, bearing little more than their incredible stories. Eggers, the prolific writer, publisher and social justice advocate, was traveling with a young man named Valentino Achak Deng. The two had met in Atlanta through the Lost Boys Foundation, a group that helps Sudanese refugees build stable lives in the United States, and Eggers had agreed to help Deng write his autobiography.

Their collaboration led to What is the What, Eggers’ novel about Deng’s walk out of southern Sudan among hundreds of boys escaping the carnage of war. But it also led to something more.

On their journey back to Sudan, Eggers and Deng met three Dinka women who’d recently returned to Marial Bai after being enslaved for years in the north during the civil war. “None of the three spoke Dinka anymore,” Eggers remembers. Losing their language was only one way their identities had been erased. Their names had also been changed to Arabic ones. One of the women had left five children with her captor. The meeting haunted Eggers and Deng.

“What about them? What about their stories?” Eggers asked. “I guess what we both talked about a lot on that trip and afterwards was that his story wasn’t the only one that needed to be told.” What is the What would go on to become a best seller, but Eggers and Deng vowed to return to tell the stories of more survivors of Sudan’s civil war.

Teaming up with Lola Vollen, a human rights activist and medical doctor, Eggers founded Voice of Witness, an innovative nonprofit that records the narratives of those who’ve survived some of the most harrowing experiences on earth. Since Eggers was already a publisher, they could use his company, McSweeney’s, to put survivors’ stories into print—to “amplify” them, in the organization’s parlance. Working with students in a class they taught together at University of California, Berkeley, Eggers and Vollen collected 50 testimonies from men and women in the United States who’d been wrongfully convicted, many of whom had been on death row. These served as the basis of the group’s first book, Surviving Justice: America’s Wrongfully Convicted and Exonerated.

Since its founding in 2004, Voice of Witness has published ten more titles that chronicle the little-known lives of those caught in some of the worst and least understood catastrophes of our time. Through extensive face-to-face interviews, it has explored undocumented immigrants, the struggles of refugees, the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and, this year, Chicago's public housing projects. And now, by broadening its innovative education program, Voice of Witness is expanding its reach even further.

The idea behind the series is to eschew the top-down method of telling history through the eyes of the “great men” who directed events in favor of returning authority to those who actually lived through them. “If journalism is the first draft of history,” says Mark Danner, a founding member of the VoW board of advisers and the author of trailblazing books about human rights problems, “then the voices of witnesses are the pith of it.”

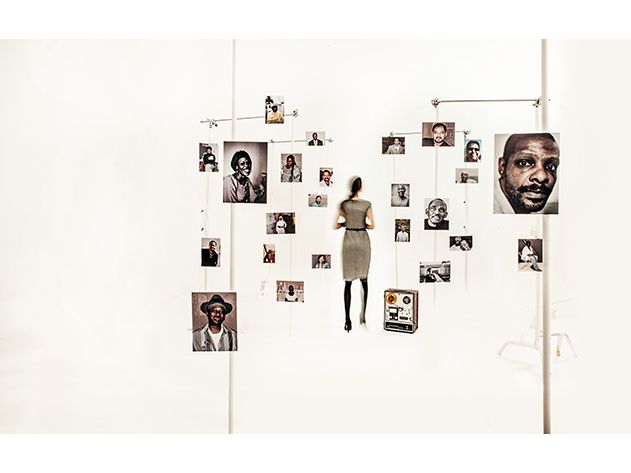

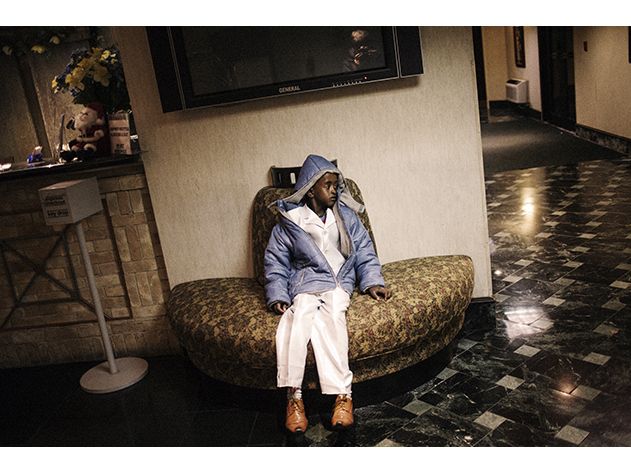

Published between covers of slick and inviting vellum, these collections of searing testimonies are, above all, good reads. Recent titles employ powerful photographs as well as narratives. Refugee Hotel, for instance, a collaboration between Gabriel Stabile, a photographer, and Juliet Linderman, a writer, presents stories of those struggling to make it in America in a book of a startlingly unconventional design: pliable postcards bound into a coffee-table book.

“Empathy is the basis of all these stories,” says Mimi Lok, executive director of Voice of Witness. “Once you connect with someone, once you acknowledge that your understanding of an issue can be broadened and challenged, it’s transformative,” Lok adds, “not just for the reader, but for the interviewer and the person who is being interviewed.”

This is where education comes in: Through its pioneering schools program, VoW worked with 85 teachers to reach some 1,400 students last year. The effort, conducted through in-school visits, workshops and training sessions, centers on teaching young people the group’s distinctive method of gathering oral histories. Organizers know from experience that the act of interviewing a subject has a remarkable impact on students—not just on giving deeper meaning to the crises of the past, but on gaining greater understanding of the world around them. To this end, there’s a maxim that Lok and the rest of the VoW staff repeat as a mantra: Empathy, they like to say, is the highest form of critical thinking.

***

Voice of Witness is run out of a storefront in San Francisco’s Mission District that sits across the street from 826 Valencia, Eggers’ award-winning tutoring program. More recently, Eggers started Scholarmatch, an initiative that helps students find money for college and which now shares space with Voice of Witness and McSweeney’s at 849 Valencia Street. Pass through a doorway and the right side of the open room is lined with desks manned mostly by rumpled, bearded folk in shirts inspired by lumberjacks. This is the staff of the McSweeney’s literary enterprise. To the left of the room, the six staff members of Voice of Witness occupy a small bank of desks. In their center sits Mimi Lok.

Growing up in one of only two Chinese families in a little town outside London, Lok knows from experience what it feels like to be on the outside. A 40-year-old writer, activist and teacher, Lok came to the organization in 2007 as a Voice of Witness interviewer working with undocumented Chinese workers. Six years ago, the group had a budget of roughly $30,000 and no dedicated staff. “There was a small pot for VoW that was largely made up of donations from a few good souls, including Dave,” says Lok, who recalls scrambling to procure one of three shared tape recorders.

By 2008, the group had scraped together more money and Lok came on board as executive director. She began fund-raising just as the global financial meltdown got underway. Simultaneously, she created an infrastructure for the growing staff, which has expanded from Lok alone to six paid employees. (The budget has grown to about $500,000 today.) At the same time, Lok edited the series’ books and turned VoW from one of McSweeney’s book imprints into a nonprofit organization of its own. She still spends her days doing everything from soliciting funds—the principal source of money for the $50,000 to $70,000 that each book requires—to line editing and scanning proposals for the next great idea.

The role of empathy in the work of Voice of Witness is so profound that the interviews have altered the course of participants’ lives. “It felt like being in the room with a counselor,” says 28-year-old Ashley Jacobs, who was interviewed by a charismatic Voice of Witness staffer, Claire Kiefer, in 2009. “I’d never ever spoken about anything I went through,” Jacobs said. “No one ever asked me about it. My family didn’t know how to. So I kind of concluded in my mind that if I don’t speak about it, then I’ll forget.”

Jacobs served six months for embezzling small sums of money from her job. Pregnant at the time of her incarceration, she knew she would have to give birth as a prisoner. But the experience shocked her: While shackled, she was given Pitocin—a powerful drug used to induce labor—against her will. Then she underwent a forced C-section. In the midst of this ordeal, Jacobs, in chains, recalls being harangued as a terrible mother and told that the hell that she was going through was her fault. Once her son, Joshua, was born, she had to leave him at the hospital as she was shuttled back to the prison infirmary and, eventually, to her cell. (Her boyfriend brought the baby home.)

The trauma and shame lodged within her for a year until Kiefer showed up at her door with a smoothie and a box of pastries. Kiefer, a poet who’d taught creative writing to men and women in prison, had no rules, no set agenda. She didn’t jump right in to ask about the story’s goriest details. Instead, she played with the baby for a while on the floor of the bare-bones apartment and slowly asked Jacobs to talk about her childhood, to tell her life story, “from birth to now.”

“I was able to cry. I was able to take breaks,” recalls Jacobs. “I was able to get everything out that I’d been holding in. She never rushed me. She cried with me sometimes. Before she left, I knew I’d gained a friend.”

Jacobs’ story became the lead narrative in the Voice of Witness title Inside This Place, Not of It: Narratives from Women’s Prisons. From the interview to the point of publication, Jacobs controlled the process. Using a pseudonym at first, she told her story in her own words and signed off on the final version for publication—a process she called “a cleansing.”

“So many people have had their narratives taken from them, or been called prisoner, guilty, slave, illegal—all of these different terms where people feel like their identity isn’t under their control,” says Eggers. He found a model for his work in journalist Studs Terkel, who got his start as a writer for the Works Progress Administration using oral history to chronicle the lives of Americans during the Depression in Hard Times. “Suddenly being able to tell your story, to have it told expansively—anything you want to include you can include from birth to the present—there’s a reclamation of identity.”

Now 43, the crusading Eggers spends his time and talent in service of a host of underreported causes, along with his tutoring programs, his literary magazine and his publishing company. Eggers rocketed to fame in his early 30s for his own memoir, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. And this fall he stirred debate with a best-selling dystopian novel, The Circle, which tackles themes of privacy in the Internet age. Despite the breadth of his interests, Eggers keeps tight focus on Voice of Witness above all. “The books that Voice of Witness has done have been the closest editing that I’ve done in the last ten years,” he says.

Although the original intention had been to focus the series on international human rights crises, the group found abuses closer to home, too: The 11 titles to date are almost evenly divided between domestic and international issues. There are books in the works about Palestinians and Haitians, and one on human rights and the global economy entitled Invisible Hands.

This isn’t traditional journalism told in the third person and claiming objectivity. Instead, these are tales told in the first person, and as such, they own their subjectivity right upfront. Although the books are carefully fact-checked, they are also left to the narrator’s point of view. Eggers has a perspective and a purpose: to build a broader and more inclusive understanding of history.

In his own work, Eggers aims to write books that directly benefit those he writes about—he has even started foundations for some of them. But the catharsis that VoW books bring to their subjects has also been an unexpected benefit of the work. “Even if the books didn’t exist, just to be able to participate in their healing has been incredibly important and central to us,” Eggers says, referring to this as a kind of “reparation.”

***

Perhaps the biggest challenge Lok and Eggers face is spreading their message. McSweeney’s publishes just 3,000 to 5,000 copies of each title, but hopes to magnify their impact by using them in classrooms across the country. It’s not just a matter of teaching their content about civil war in Sudan or Colombia—it’s about changing the way history is taught.

The most essential lesson is the art of listening, says Cliff Mayotte. He and Claire Kiefer, the poet who interviewed Ashley Jacobs, make up the VoW’s thriving education program, which began in 2010 with the help of Facing History and Ourselves, a decades-old organization that teaches social justice around the world. Facing History and Ourselves helped the fledgling VoW craft a curriculum, which was recently published in a teacher’s manual, The Power of the Story. Now Mayotte and Kiefer travel around the San Francisco area and teach students in private schools and underfunded public high schools the principles behind a successful oral history. This year they have begun to take their teachings nationwide, traveling to Chicago, Eggers’ hometown, to discuss the latest book, about the city’s public housing projects.

On a recent afternoon, Mayotte and Kiefer drove his 19-year-old Toyota Camry to Castilleja, a private girls’ school in Palo Alto, California, one of the wealthiest ZIP codes in the United States. The two were team-teaching 66 sophomores how to ask one another intimate questions about the most difficult experience they’d faced in their short lives—and how to answer them. Their lessons were more about mutual respect and practicing empathy than they were about any specific technique.

The day’s exercise was only the beginning of the project. The students were preparing to interview mostly undocumented day workers at a jobs and skills-building center in nearby Mountain View. As the uniformed girls in their baby-blue kilts paired up to speak to classmates they hardly knew, Mayotte scrawled his favorite quotation from the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on the blackboard: “You can’t tell a single story of any place, person, or people. The single story creates stereotypes. The problem with stereotypes is not that they’re untrue, it’s that they are incomplete.” These collections of oral histories defy stereotypes: Their very method is to let a broad swath of people speak for themselves.

***

After Ashley Jacobs’ positive experience with Voice of Witness, she risked going public as an advocate for the rights of pregnant women in jail, even feeling confident enough to eschew her pseudonym in favor of her real name. One of VoW’s success stories, Jacobs also trains interviewers in how to reach out to people like her. “The book actually gave me a voice,” she said recently by phone from Tampa. She has stood in front of throngs on the steps of the Georgia state capitol to speak on behalf of a bill that would end the shackling of pregnant prisoners. “It opened up the doors for me to be able to speak about what I went through, for people to see me for who I am.”

For Eggers, Jacobs’ story is one of a growing list of unforgettable narratives gathered by Voice of Witness. As a teacher, he introduced her narrative to his high-school students at 826 Valencia. “They were so drawn to her story and blown away by it,” he says. The class voted to include the story in Best American Non-Required Reading, yet another Eggers’ endeavor. Jacobs’ experience surprised and confounded the students. “Everything they thought they knew was overturned,” Eggers says. "And eventually they came to understand how somebody they would have seen as a statistic or a ghost behind bars is someone they could fully identify with and root for and love."