Ten Technologies That Will Change Our Lives, Soonish

A scientist and admired cartoonist explore how today’s research is becoming tomorrow’s innovations in a new book

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/bf/aebf0aa7-3748-44fa-ba63-dcea783d9ed9/bioprinting.jpg)

Popular science is more popular than ever, and for good reason: technology is advancing at such a breakneck pace that each day brings a fresh crop of it-couldn’t-have-happened-five-years-ago announcements.

This week alone, science and technology news included articles on a new negative-emissions power plant in Iceland that converts carbon dioxide to stone, an honest-to-goodness ion thruster, and virtual humans helping uncover PTSD in soldiers returning from deployment. If you don’t know much about how this has all come about, as exciting as it may be, these stories can be confusing, bewildering or even disturbing.

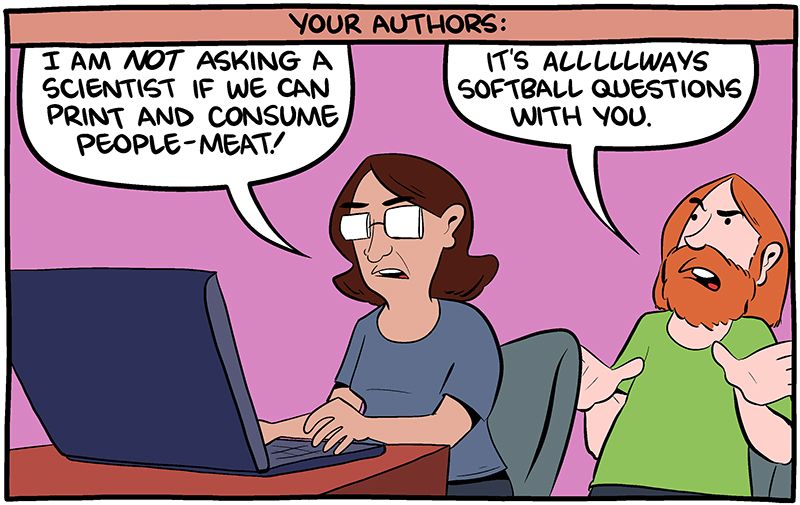

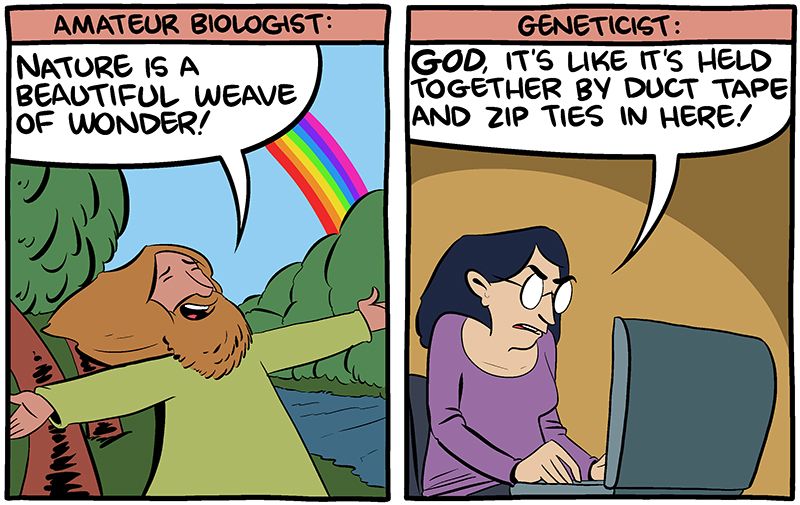

With their new book, Soonish, Zach and Kelly Weinersmith set out to do a deep dive on 10 of the most potentially important technologies that are under development today.

Available tomorrow, Soonish starts in space, looking at reusable rockets and asteroid mining, then shifts to Earth with an exploration of fusion power, programmable matter and robotic construction. The book concludes with discussions on synthetic biology (think creating malaria-free mosquitoes) and printing new organs.

Zach, the wit behind the popular Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal webcomic, and Kelly, a parasitologist at Rice University, enlisted an army of scientists, researchers and even a Nobel Prize laureate to help them break down some really complicated science in a (very) funny, everyday voice, punctuated by laugh-out-loud comic panels.

Zach, you’re a cartoonist who went back to school to study physics, and Kelly, you’re a parasite researcher. What’s the fascination with technology?

Zach: The original idea was that this could be a book for a precocious 15 year old, an exploration of things that might be important in just a few years.

Kelly: Our favorite activity—before kids—was to walk around and talk about new stuff we’d learned. The walking around didn’t end up happening so much after our daughter was born, but this gave us an opportunity to read about stuff that neither of our jobs put us in contact with often, and summarize it in a funny chapter.

Many of the topics you chose to include in the book—robotic construction, programmable matter, computer-brain interfaces—could make pretty compelling TED talks or videos. How does a book help people understand them better or differently?

Zach: We wanted more weird stories and the opportunity to explain in-depth what’s going on. Lots of people watch these videos of the first phase of the Space-X rocket coming back to land, and that’s neat. But in a book you can break down the physics and economics of why that changes everything.

There’s tons of other, seemingly unrelated science throughout the book. Is this really just a “hey, look at this shiny new tech, but secretly this is a crash course in the real science that’s happening all around you?”

Zach: When you’re trying to understand a technology completely, there are a lot of explanations that require you to understand, for example, basic biology or physics. One of the things that would make us really happy is if people read the book because they’re excited about the technology, but then come away with some better understanding of how proteins or DNA or basic particle physics works.

Kelly: That’s how science works. There’ll be a surprise finding in a different area that will move the whole field forward. It probably won’t be NASA that develops a carbon nanotube cable for a space elevator, but a company that wants to make a bulletproof vest more bulletproof.

The book covers a lot of ground—were there any really surprising moments that stand out?

Kelly: One interview that really blew my mind was with Gerwin Schalk, for the section on brain-computer interfaces. I was asking him about the future of the field, and thought it would be along the lines of helping people with physical disabilities overcome them. But his answer was that at some point, we’ll all load our brains onto the cloud and be one connected mind. I didn’t know what to say—that sounds horrible to me.

So I asked all the other people I interviewed for that chapter, is this something everyone in the field recognizes as a direction the field is going in? And they all said, yeah, we probably will be able to load our brains into a super computer. It must be really interesting to go to their conferences. It’s fascinating to think about the implications of whether you want to be a part of that future.

How do you think this book might be viewed 10 years from now, given the current pace of tech advancement?

Kelly: Maybe people will look back at the whole book and be like “Oh, that’s cute, but now everyone’s CRISPR-ed themselves.” But we explicitly didn’t want to say when we thought these technologies might become common, since so many of them require a giant leap that maybe would never come.

Zach: There will probably be new developments, but the basic outlines are still the same. Space elevators have never been built, so we have to talk about it more abstractly, but the basic physics problems will almost certainly still be with us in 10 years. That’s generally true of all the technologies we discuss.

Did learning so much about these in-process technologies change your worldview at all?

Kelly: One thing that hit home more than I expected is how little I know about things I thought I knew a lot about. With Jordan Miller , for instance, and his work on organ printing—even though you still can’t print anything thicker than a dime, he’s working on tissues with capillaries that are growing and branching out on their own because they’re really happy in the environment he’s made for them. Realizing what has to be overcome can be depressing, but we’ve made great strides. I’m definitely optimistic.

Zach: It’s like when people say, where’s my flying car? Well, there are 80 versions of a flying car—planes, helicopters, autogyros. Pick one! So what they mean to say is, why can’t I have a flying car that works because of some impossible physics I’m imagining? If you can see the incremental steps, you know the constraints behind them, so you can be more optimistic. If you can’t see them, then you’re perpetually disappointed.

So you have a mind-blowing sci-fi saga that you’ll be able to write now that you’ve done all this research on future technology, right?

Zach: We were joking that we could do some kind of a comedy about organ printing. What if there was this world where every part of your body is disposable? Everyone could act way more dangerously. You could go to a party and light your hand on fire, and just go home and print a new one. And maybe in that world, that is okay.

What technology included in the book would you be first in line to buy if you could get it tomorrow?

Kelly: For almost all of them, we’d like to be in the back quarter of the line when they come out, so we can be sure everything is figured out. We’d love to go to space on an elevator, but not as the first ones. Maybe in the first 25th percentile if one of us had a genetic disease.

But straight-up first in line? Origami robots.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)