The Surprising Origins of Kotex Pads

Before the first disposable sanitary napkin hit the mass market, periods were thought of in a much different way

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/b2/3bb21c48-d7f4-48e2-897f-5ae2a29612f5/nurses.jpg)

What’s in a name? For Kotex, the first-ever brand of sanitary napkins to hit the U.S., everything.

The disposable sanitary napkin was a high-tech invention (inspired, incidentally, by military products) that changed the way women dealt with menstruation. It also helped to create modern perceptions of how menstruation should be managed through its advertising, which was both remarkably explicit for its time but also strictly adhered to emerging stereotypes about the “modern” woman of the 1920s should aspire to. Kotex sanitary napkins paved the way for the wide variety of feminine hygiene products on the market today by finding an answer to the crucial question: How to market a product whose function can’t be openly discussed? “Kotex was such a departure because there just wasn’t a product” previously, says communications scholar Roseann Mandziuk.

Prior to Kotex’s arrival on the scene, women didn’t have access to disposable sanitary napkins—the “sanitary” part really was a huge step forward for women who could afford these products. But the brand’s creator, Kimberly-Clark, also reinforced through its advertising campaigns that menstruation was something to conceal and a problem for women, rather than a natural bodily function.

In October 1919, the Woolworth’s department store in Chicago sold the first box of Kotex pads in what might have been an embarrassing interaction between a male store clerk and a female customer. It quickly became clear that giving Kotex sanitary napkins name recognition would be vital to selling the product, and the company launched a game-changing advertising campaign that helped to shape how menstruation–and women–were seen in the 1920s.

“Ask for them by name” became an important Kotex company slogan, Mandziuk says. Asking for Kotex rather than “sanitary pads” saved women from having to publicly discuss menstruation–particularly with male shop clerks.

In 2010, Mandziuk published a study of the 1920s ad campaign promoting Kotex sanitary napkins, focusing on advertisements that appeared in Good Housekeeping. Kotex’s campaign, which began in 1921, was the first time sanitary napkins had ever been advertised on a large scale in nationally distributed women’s magazines, and Mandziuk says they represent a break in how menstruation itself was discussed. By giving women a medically sanctioned “hygienic” product to buy, rather than a made-at-home solution, they established a precedent for how menstruation products were marketed up until the present day.

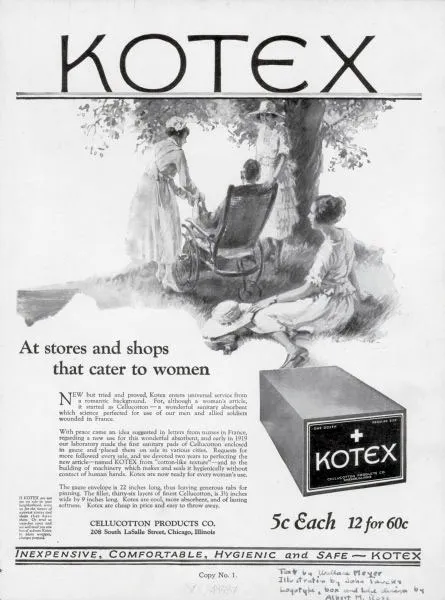

For their time and place, the advertisements are almost shockingly explicit–although, like many modern ads for menstrual products, they never explicitly state their use. “All feature a single woman or a group of women in active, yet decorative poses,” Mandziuk writes in her study. The first ad to run in Good Housekeeping describes Kotex sanitary napkins as the key tool for ensuring “summer comfort” and “poise in the daintiest frocks.” But it also describes details like the size of the pad and how to buy them, although the pads were never actually pictured in the ads. The ads also promised they came “in plain wrapper.”

Another ad shows two women in an office environment. “There is nothing on the blue Kotex package except the name,” it promises, adding that the purchase is small enough to fit in a shopping bag. Advertising for Kotex sanitary napkins framed menstruation as something that could–and should–be concealed.

“It was really playing off the anxiety of women wanting to fit into this new, confusing modern culture and be a part of it,” Mandziuk says. “And yet, to be a part of it, you had to hide even moreso that you had this secret, or this thing that was disturbing to men.”

Though some Kotex sanitary napkin advertisements show women in real working environments, throughout the 1920s, the advertising increasingly moved away from being about the real working women who might benefit most from the product and more into the sphere of an ideal. The woman shown in the ads might be an elegant picnicker, a partygoer or even a traveller, but she represents an ideal “modern” woman, Mandziuk says.

This presented women with a catch-22, she says: While Kotex did make the lives of 1920s women who could afford to buy the pads better, its ads framed menstruation as a handicap that required fixing rather than a natural process.

Before Kotex sanitary napkins hit the market in 1921, most women relied on homemade cloth pads (although some storemade cloth pads and disposables had been on offer since the late 1880s.) Different women had different ways of dealing with their periods each month and there was little social expectation that all women would deal with menstruation in exactly the same way. At the same time, menstruation was a commonly accepted (if still socially concealed) reason that women might not be in the public eye during their periods.

“[Menstruation] still was hidden among the society of men,” says Mandziuk. But between women, particularly women of the same family or who shared a household, it was normal to manage menstrual supplies like handmade pads or rags together.

“Practices for making cloth pads varied,” writes historian Lara Freidenfelds in The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America–but they were all based around reuse of things that already existed. “We used, just, old sheets, old things that you had around the house and things like that,” one woman told her during a series of oral history interviews.

Some women threw away their bloody cloths, writes Freidenfelds, but others washed and reused them. Either way, menstruation had the potential to be a messy and inconvenient business, as rags were hard to hold in place and didn’t absorb very much fluid.

For women who could afford such things and had access to them, there were options such as the “Hoosier” sanitary belt, which held cloth pads in place, or Lister’s Towels, possibly the first-ever disposable option, but the use of such products was not widespread, Mandziuk says.

“Kotex would have obvious appeal when it appeared on the market,” she writes, “given the discomfort and inconvenience of cloth pads, and growing expectations that women would work and attend school with their usual efficiency all month.

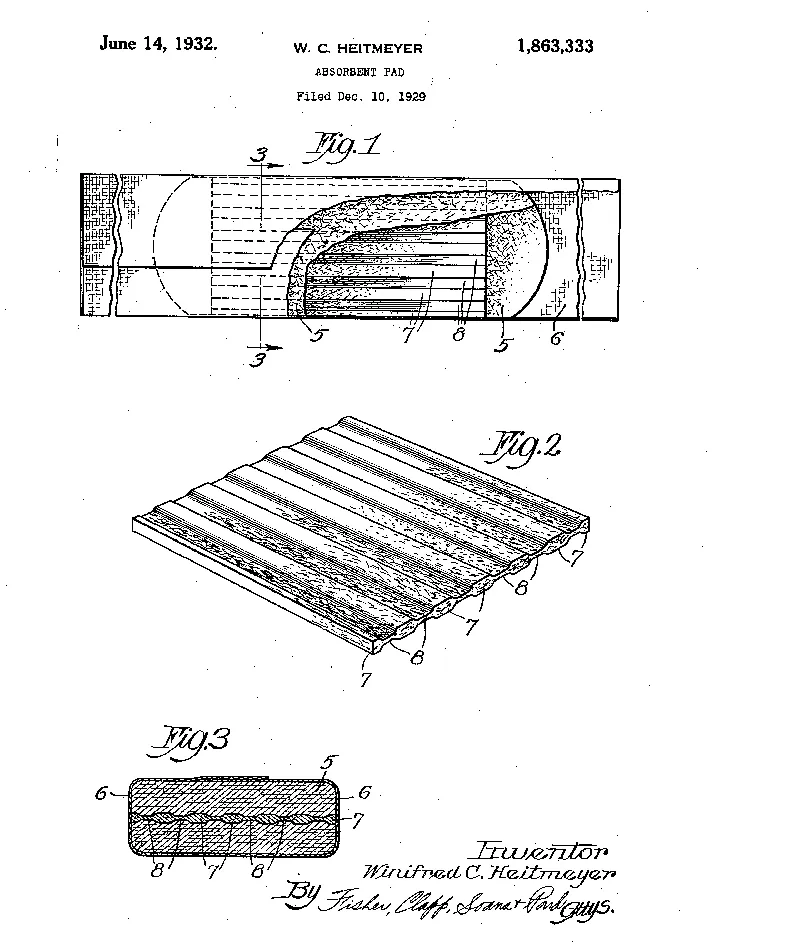

Like a number of other products that first came to market in the 1920s, Kotex sanitary pads originated as a wartime invention. Kimberly-Clark, an American paper products company formed in the 1870s, produced bandages from a material called Cellucotton for World War I. Cellucotton, which was made of wood pulp,, was five times as absorbent as cotton bandages but much less expensive.

In 1919, with the war over, Kimberly-Clark executives were looking for ways to use Cellucotton in peacetime. The company got the idea of sanitary pads from the American Fund for the French Wounded, according to historians Thomas Heinrich and Bob Batchelor. The Fund “received letters from Army nurses claiming they used Cellucotton surgical dressings as makeshift sanitary napkins,” the pair write.

Kimberly-Clark employee Walter Luecke, who had been tasked with finding a use for Cellucotton, understood that a product designed to appeal to about half the country’s population could create enough demand to take the place of the wartime demand for bandages. He jumped on the idea.

But Luecke ran into problems almost immediately. The firms he approached to manufacture sanitary napkins from Kimberly-Clark’s Cellucotton refused to do so. “They argued that sanitary napkins were “too personal and could never be advertised,” Heinrich and Batchelor write. Similar doubts plagued Kimberly-Clark executives, but Luecke kept pushing and they agreed to try the idea, making the sanitary napkins themselves.

The name Kotex came from one employee’s observation that the product had a “cotton-like texture.” “Cot-tex” became the easier-to-say “Kotex,” creating a name that–like another Kimberly-Clark product, Kleenex–would become a colloquial way to refer to the class of product itself.

For the firm that Kimberly-Clark hired to do the advertising, their successful ad campaign gave them bragging rights. “I think they kind of patted themselves on the back, that if they could sell this, they could sell anything,” Mandziuk says.

For the women who used them, Kotex sanitary napkins changed how they dealt with menstruation. They set a precedent for how nearly all American women would understand menstruation and how they would deal with it up to the present day.