This Pump Could Make Blood Transfusions Safer and Cheaper in the Developing World

The Hemafuse gives doctors a sterile way to suction, filter and retransfuse patients’ blood in places without electricity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/dc/eedc98dd-dc9d-446b-944e-9ac2172c2665/hemafuse.jpg)

If you needed an emergency blood transfusion in the developing world, the doctor might show up with a soup ladle. It sounds horrific, but it's true. Medical professionals, in some cases, use ladles to scoop out pooled blood, run it though gauze to filter out clots and then pump it back into a patient’s body. In some places in sub-Saharan Africa, even relatively well-supplied hospitals, it is the best option available.

To address that need, Sisu Global Health, a medical technology company run by the three women—Gillian Henker, Carolyn Yarina and Katie Kirsch, who all spent time working in healthcare in the developing world—created the Hemafuse, an electricity-free autotransfusion device that lets doctors reuse a patient’s own blood, in a sterile way, when they’re hemorrhaging.

Five years ago, Henker and Yarina were studying engineering at the University of Michigan. They spent time in Ghana and India respectively, working on medical device projects. Henker saw the soup ladle technique firsthand during ruptured ectopic pregnancies, and saw the need for blood during emergency surgeries. The two women connected with Kirsch, who had worked in India with Yarina, and they started working on devices that would allow hospitals to cleanly reuse patients' blood.

The medical engineers ultimately wanted their product to be affordable. Part of the problem with current blood transfusion methods, in places like Ghana, is that donor blood can be expensive, unavailable or potentially tainted with HIV or other diseases. Autotransfusion devices used in developed countries, like the Haemonetics Cell Saver, rely on electric suction to pull out the pooled blood and a centrifuge to process it before it goes back into the body. They're dependent on a power source, and both the machine and the consumables used to store and process the blood are expensive.

Henker, Yarina and Kirsch knew they wanted to make surgeries, especially around women's and specifically maternal health, less risky, but it took them a while to settle on the Hemafuse. They worked on other devices, including an electricity-free centrifuge, before focusing on autotransfusions.

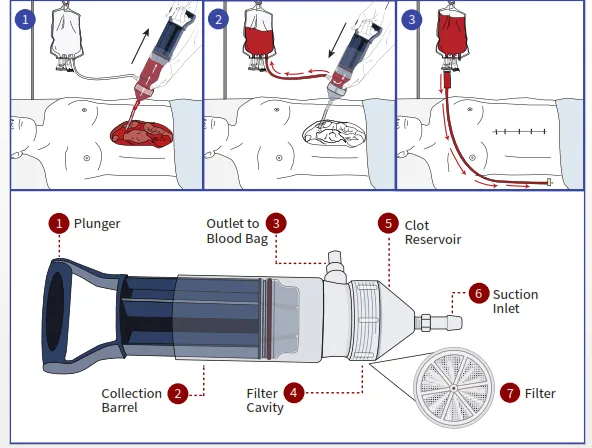

The Hemafuse, which looks like a giant syringe, is handheld and doesn’t require any electricity. Using the device, blood is suctioned out of the body cavity where it’s pooled into a chamber, then pushed through a filter, which traps clots and bone particulates, into a blood bag where it can be retransfused. The process takes about 10 minutes, as opposed to the 30 needed for the ladle, and only requires one doctor, not a team.

In developing the device, Kirsch says they were really conscious of the business model. They worked with the Ministry of Health in Ghana and other stakeholders to make sure it was something necessary and impactful. They didn’t just want it to be an aid program, they wanted it to be a for-profit venture that was also financially sustainable in the developing world. They’d seen how cost had been a barrier for patients and hospitals to get blood, and they wanted to build something that would be affordable and useable in the long term. The full-scale production model of the Hemafuse costing around $3,000 will come in a packet with 50 filters; Kirsch says this will bring the cost of a transfusion down to about $60 per patient, much less than the $250 that a bag of blood typically costs.

This winter, Sisu Global Health is starting its first human clinical pilot in Zimbabwe, where the company will train doctors to use the device in working clinics. "We're training and facilitating to get that basic data for how it works in the field, and we're really confidant that it will go well," Kirsch says. After their trial in Zimbabwe, they’ll head to Ghana, where they plan to set up a production hub, to better reach other countries in West Africa.

Sisu isn't a one-trick pony either. The company plans to work on distributing other low-cost, high efficacy medical devices, like the (r)evolve, a centrifuge that Yarina developed, which will allow clinics to cheaply run diagnostic tests for diseases, including HIV, malaria, hepatitis, syphilis and typhoid fever, without electricity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)