Rethinking How We Build City Streets

Sidewalk Labs envisions modular streets that can morph to meet the everyday needs of a neighborhood

:focal(677x354:678x355)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/cd/29cd9e3d-ff33-4cb4-9efa-8a878f2233a3/dynamic_street_1.jpg)

When streets change, it’s usually not a good thing. Who among us takes pleasure in spreading potholes, deafening roadwork or time-sucking detours?

But what if roads could be designed to serve our needs? What if they could turn into fungible spaces that become more than traffic lanes?

That’s the idea behind a paving system proposed as part of an ambitious project to reinvent what it means to live in cities. It's currently on display in a converted industrial building in Toronto where prototypes of potential urban innovations are being shared with the public. Visitors can not only walk around on the experimental surface where 232 hexagonal blocks with embedded lights have been assembled into a "street" 12 yards wide, but they also are invited to digitally reconfigure the space to use it in various ways.

That "Dynamic Street" concept is one of the first big ideas to be exhibited as part of a cutting-edge project called Sidewalk Toronto, a joint undertaking by Sidewalk Labs—a sister company of Google—and Waterfront Toronto, a public agency, to incorporate digital and technological innovations into the rebuilding of an aging, 12-acre property near Lake Ontario.

The notion of having streets become “dynamic” by being able to morph into pedestrian walkways or outdoor plazas on different days or even different times of the day comes from Sidewalk Labs and was developed by Carlo Ratti, founder of the design firm Carlo Ratti Associati and director of MIT’s Senseable City Lab.

“With this project,” he says, “we aim to create a streetscape that responds to citizens’ ever-changing needs.”

Going modular

So, what exactly does that mean? Jesse Shapins, the Sidewalk Labs director of public realm and culture, provides more specifics.

“In conventional streets, for example, the curb is an outgrowth of the introduction of vehicles,” he says. “But in a world where we can be more flexible and try to create more space for pedestrians, you might be able to remove that curb, create a flat street, and so, at different times, for different needs, the street has a larger sidewalk.”

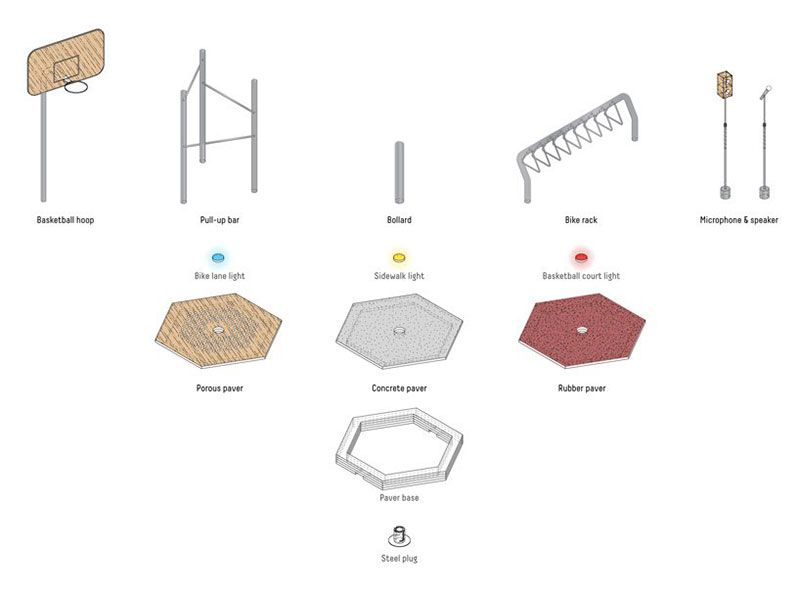

“Dynamic streets,” according to Sidewalk's vision, would not be paved, but rather be constructed of concrete hexagonal blocks, each about four feet in diameter. The lights would be a key component, indicating how a space was meant to be used at a particular time, such as for a crosswalk, a bike lane or as a pickup and drop-off lane.

The last would be designed primarily with driverless cars in mind, Shapins notes.

“With future streets, you’ll have autonomous vehicles that have a level of intelligence that will be able to keep them at a specific slow speed and prevent them from entering certain areas at certain times,” he says. “So, you can think differently about how that street works.

“Lanes in the middle could be for autonomous vehicles, and you have a sidewalk. But then there’s the area between them. Sometimes it could be used for drop-offs from vehicles, and sometimes it could be used as an extension of the sidewalk. You could even have benches there.”

Street-shifting

Shapins points out that as much as pavement can help define a place—think the cobblestone streets of Paris or the wide sidewalks of New York—it’s pretty much taken for granted as a constant of urban life. So, the idea of a neighborhood’s public spaces becoming more fluid would take some getting used to, he concedes.

“When you’re introducing a new system like this, you need to make sure that it’s always safe, and that it maintains all the standards of accessibility that we have for streets today,” he says. “This has started a conversation about how communities could have more agency over their environment, and that, of course, comes with questions about how space is allocated.”

With a streetscape meant to be more flexible, one of the matters Sidewalk Toronto will address is what drives a neighborhood’s shape-shifting. How much is determined by the data that sensors gather about how residents use the environment, and how much by their personal wishes? In theory, the former will help inform the latter. With relevant data, says Rohit Aggarwala, head of Urban Systems at Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs, “we should be able to accommodate the evolution of the neighborhood much more quickly.”

The goal of giving people much more access to what has been the domain of vehicles could play out in a number of ways, based on Ratti’s proposal. He suggests that streets could be reconfigured for block parties or even basketball games. To that end, the hexagonal blocks would include slots designed to accommodate bike racks, exercise equipment, microphone stands or basketball hoops.

Using blocks instead of pavement offers another advantage: When utility work must be done, only a limited number of blocks may need to be removed instead of tearing up the whole street. The modules also could be heated, according to Shapins, making it possible to keep a street from icing over. For a city like Toronto, that would eliminate the need for salting roads, which, over time, could result in significant financial and environmental benefits.

But Sidewalk Labs officials concede that it's too soon to say if converting urban streets to concrete blocks with lights would be financially or logistically tenable. That's something that will be explored in the coming months; for now, the "Dynamic Street" is still in the proof of concept stage. The blocks in the model on display are made of wood, not concrete.

It's also not yet clear how scaleable the idea may be, although one of Sidewalk Toronto's goals is to test innovations that ultimately could be adopted by other cities.

Among other concepts that have come up are what Shapins refers to as a “building raincoat”—a component that could extend from the bottom of buildings to provide protective cover over sidewalks—and “pop-up” spaces, such as a temporary play area for a child care center or an outdoor “room” where people could watch a movie.

“It’s about breaking down the boundaries between buildings and the outdoors,” he says.

A matter of privacy

Sidewalk Toronto is well into a year-long series of discussion sessions and town hall meetings to get the public’s feedback and bring transparency to a project that has raised questions about how this kind of public/private partnership will work. For instance, how much control will Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet, one of the world’s most powerful tech companies, have over how this neighborhood is rebuilt and ultimately, how it functions?

Of particular interest is what happens to the enormous amount of data that will be collected in what Sidewalk has said will be the “most measurable community in the world.” Project officials have said that protecting the privacy of individuals is a top priority, but not surprisingly, it’s a subject that often comes up in public meetings. Questions have been raised about not just how the data would be used, but also who would actually own it.

“We’ve been engaging with the public in a very serious way,” says Lauren Skelly, the project’s director of external affairs. “If anything, they want to see more ideas.” But, she notes, there are “real and genuine concerns” about the use of data.

Skelly says a Digital Strategy Advisory Panel of industry and academic experts is providing guidance and feedback on data privacy and other legal and ethical issues related to digital technologies.

“We will always inform people how and why data is being collected and used,” she says. “None of that should be a surprise. We will seek meaningful consent. We have made a firm commitment to not sell personal information to third parties or use it ourselves for advertising purposes.”

Skelly says a full site plan for the project will be presented in November, with a development proposal rolled out in the first quarter of 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)