There Were Listicles That Went Viral Long Before There Was an Internet

Digital scholars are zeroing in on stories that were trending way back in the 19th century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/41/3041386f-ea2a-47d8-af62-93aa39962d62/julaug2015_m07_phenom.jpg)

If you spend any time online, you’ve probably come across “Which Classic Rock Band Are You?” or “10 Hours of Walking in New York City as a Woman.” But there’s a viral sensation you likely missed: “The Fate of the Apostles,” a listicle about which of Jesus’ followers was “run through the body with a lance” or “stoned and then beheaded.” It circulated widely, appearing in a quarter of U.S. media outlets...in the 1800s.

The article is a star example from the Viral Texts project at Northeastern University, the largest-scale study ever of how content spread through the social media networks of the 19th century—newspapers. Analyzing 2.7 million pages from nearly 500 newspapers digitized in the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America database, the researchers found that about 650 articles were reprinted 50 times or more, a working definition of “viral” in the industrial age. And the most popular story types would be strangely familiar to Twitter users, says Ryan Cordell, an English professor and co-leader of the research.

Among the trending formats were listicles such as the “Age of Animals” (“a dog lives 20 years; a wolf 20; a fox 15”) and questionable health tips, like an item about the tomato (“Dr. Bennett...has successfully treated diarrhoea with this article alone”). Parenting advice was big (“From your child’s earliest infancy, inculcate the necessity of instant obedience”), as were tear-jerkers. One vignette purports to be a letter found by a husband after his wife’s death: “When this shall reach your eye...I shall have passed away for ever, and the old white stone will be keeping its lonely watch over the lips you have so fondly pressed.”The Viral Texts researchers are less interested in the specifics of the stories than in the nature of the networks that spread them. Content today is passed along by users, but these older sharing networks were controlled by editors, who exchanged subscriptions with editors at other publications during the newspaper boom of the 1800s. And just as today’s “influencers” gain outsize followings on social media, some newspapers were better connected than others. A lot of stories passed through Nashville and Wheeling, West Virginia, for example.

Also, much as touchy users today might “unfriend” you on Facebook, editors in those supposedly more genteel times were not above publicly breaking off relationships. Take this editorial from an Alabama paper, written about the Raleigh Star: “Having no more occasion for waste paper, we directed our publisher some months since to erase its name from our exchange list.”

Of course, viral content moves more quickly now, at a rate that surprises even the experts. In 2013, when Cordell’s five kids wanted a puppy, he tried to stall by telling them they had to get a million likes on Facebook first. He figured it would take months. With a cute photo, they did it in seven hours.

Compare that to “The Fate of the Apostles,” which appeared in at least 110 publications, from the Vermont Watchman to the Daily Bulletin in Honolulu. It needed more than 50 years to make the rounds.

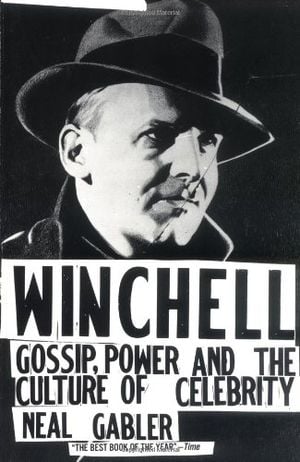

Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of Celebrity