This Language-Teaching Device Constantly Whispers Lessons In Your Ear

A conceptual gadget called Mersiv immerses language-learners in their tongue of choice

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/f7/c8f7d119-c047-4d99-b4fc-f94f30db603e/mersiv-on-person.jpg)

In the 90s, the commercial was inescapable: Muzzy, the fuzzy, green, foreign language-teaching beast, speaks in French. The scene cuts to a girl watching the BBC video course. “Je suis la jeune fille,” she says proudly pointing to her chest (translation: I am the young lady).

Since Muzzy, options for language learning videos and software have grown exponentially—Duolingo, Rosetta Stone, Fluenz, Rocket Languages, Anki and Babbel are just a few. In 2015, the language learning market worldwide reached $54.1 billion, according to a recent report from Ambient Insight, a market research firm for learning technology. Now a new conceptual device, Mersiv, is hoping to break into this booming field.

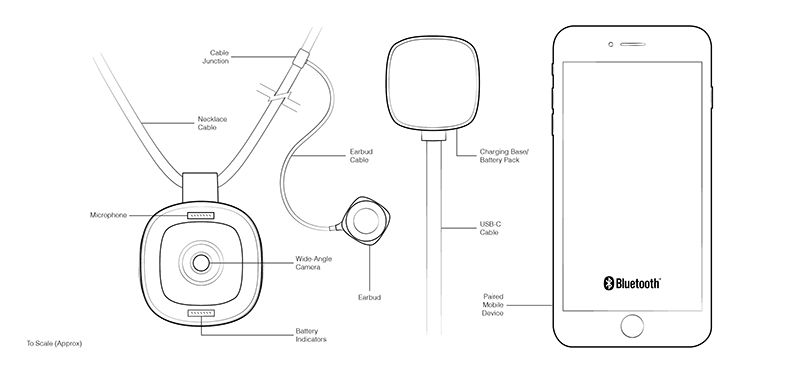

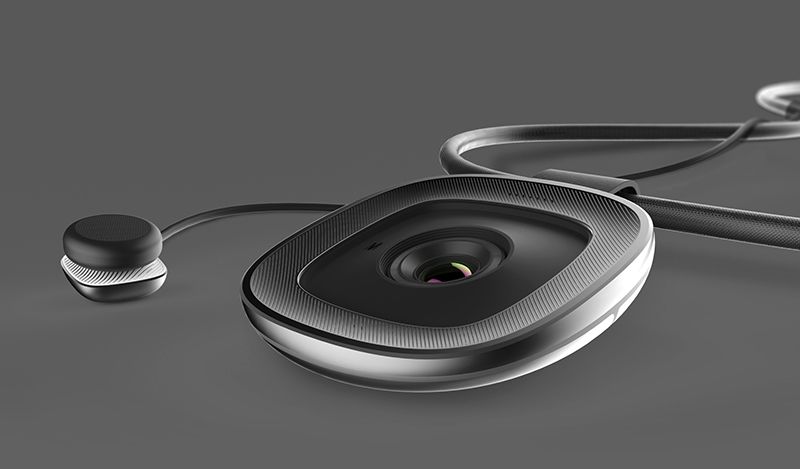

As proposed, the gadget is worn around a user’s neck, like a necklace, and features a silver dollar-sized pendant with an embedded camera and microphone. A small earbud accompanies the device, either tethered to the pendant’s neck strap or connected via bluetooth. The idea is that Mersiv captures the language-learner’s surroundings and chats with the user through the earpiece—kind of like having a language teacher constantly whispering lessons in your ear.

Joe Miller, an industrial designer at DCA Design International, dreamed up the device just a few months ago, after trying to learn Swedish using Duolingo—a website and free app intended to bring language learning to the masses. In a game-based set-up, users translate sentences from one language to another, gaining knowledge while helping to translate internet content.

“After six months of doing it, I was just starting to get frustrated,” he says. “I was getting to a level and plateauing and finding it hard to just keep progressing, to keep finding the time.”

Rudimentary understanding of easier-to-learn languages, such as French, Spanish and Swedish, requires roughly 480 hours of study. And the number goes up with language difficulty, requiring somewhere near 1,000 hours to achieve a similar level of proficiency in languages like Chinese or Japanese. Miller realized that if he only spent a half hour or less a day, it would take him years to learn his language of choice.

So the designer, who mainly works on consumer electronics and furniture, set out to design a device that could essentially immerse users in a foreign language to speed the learning process. He dubbed the project Mersiv.

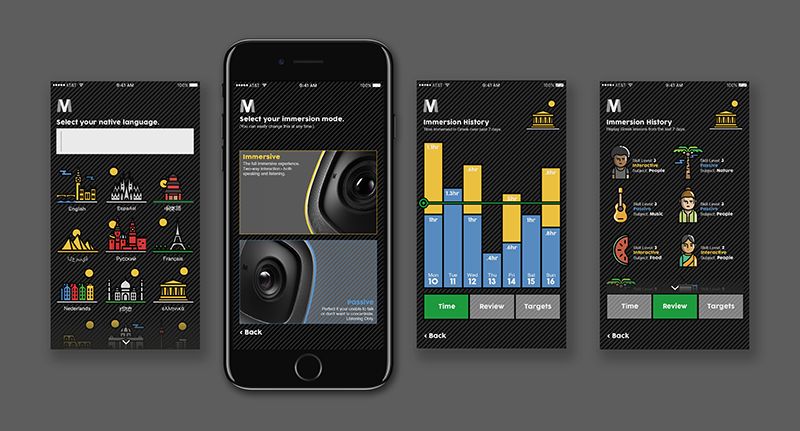

The language learner can choose one of two modes, “passive” or “interactive.” In passive mode, the camera pendant takes pictures of the user’s surroundings, beaming the images to a smartphone app that processes them and discerns basic objects—table, bookshelf, vase, bottle of wine. The program would then describe the environment in the user’s language of choice through the earbud.

In interactive mode, the language learner would have the ability to talk back to the device, answering questions and taking oral quizzes. Through the phone app, they can select both the immersion level (how frequently the device gives lessons) as well as skill level, building to more challenging conversations.

The demonstration video shows the user eating a bowl of pasta. A mechanical woman’s voice chimes in: “It looks like you are eating something. What are you eating?”

“Pasta,” the user responds.

“Can you say pasta, but in Swedish?” the device prompts.

Miller is now working in conjunction with his company to develop the first of “probably many” prototypes, he says. And though the device is still in a conceptual phase, it can actually be created by connecting a variety of existing technologies.

He hopes to use a wide angle micro camera and microphone similar to what is found in most modern cell phones. A bluetooth chip will beam the images from the camera to the user’s phone, where the software then takes over—this is the biggest sticking point in the endeavor, says Miller.

For the application, Miller plans to link object recognition software, such as Cloud Site, with Google Translate, which he needs to then loop back to the earpiece of the device to relay the information. Since the project is still in an early conceptual phase, there is much to consider moving forward.

For one, Miller still has a ways to go before he can convince the experts that Mersiv will be an effective tool.

“My bottom line is: Technology is very clever,” says Andrew D. Cohen, professor emeritus of second language studies at the University of Minnesota, who is not involved in the project. “But what are they doing with it? How interesting and how useful is the information? That's where the real genius lies.”

Now working on learning his thirteenth language, Cohen is dubious about the bold claims of most language-learning software. “Anything to pull you into language study [is] great,” he says. “But people can get deceived into thinking there's some easy way.” Languages take years of dedicated study and interaction with locals to truly master the intricacies and turns of phrase.

This critique extends far beyond Mersiv, Cohen explains. Most language courses today will teach you to order a bowl of soup. But few will equip you with the language skills necessary to discuss the consequences of the most recent election, he says.

There are some concerns about automatic translators, such as Google Translate, the software Miller currently plans to employ at the nexus of the Mersiv program. Cohen argues that all non-human translators are innately flawed at this point. “They don't get the context. They don’t get the pragmatics. They don't get the intonation,” he says.

With the rollout this fall of the Google Neural Machine Translation (GNMT), however, the system has seen vast improvements. GNMT is a “neural network” that the Google geniuses trained to translate full sentences, rather than components of each phrase. Though accuracy has increased by as much as 60 percent, it still has a ways to go.

"GNMT can still make significant errors that a human translator would never make, like dropping words and mistranslating proper names or rare terms," Quoc V. Le and Mike Schuster, researchers on the Google Brain team explain to Nick Statt at The Verge. Even in the new system, context recognition remains an issue, , since sentences are still translated in isolation.

Cohen gives an example of related issues using a military voice recognition translator. He spoke the phrase, “Oh darn, let me pick those up,” into the device, which converted it to Spanish. But instead of the “oh” of annoyance, it used the “ah” of insight. And for darn, the device inserted a verb, as in “to darn socks.”

There are few shortcuts to language mastery, Cohen cautions. The hope is that a device like Mersiv can help speed the initial stages of learning a language, assisting students in achieving basic skills as well as the confidence to interact with native speakers to learn more. But lessons learned from most software programs are just the tip of the linguistic iceberg.

The metaphorical hunk of ice, that is—not the lettuce.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)