When a 7.1-magnitude earthquake rocked Southern California on July 5, it was the most powerful to hit the state in 20 years. Cracks snaked through buildings, roads split, and fires exploded and raged at a mobile home park in Ridgecrest, the epicenter. And yet, within a few hours, a team of chefs from World Central Kitchen was there. WCK, a nonprofit founded by José Andrés, 50, commandeered a middle-school kitchen and, with the help of local chefs and volunteers, began cooking. By lunchtime the next day, there were thousands of sandwiches made by assembly line at a long foldout cafeteria table. By dinner, first responders and scores of displaced residents were being delivered hot plates of smoked paprika roasted chicken over rice studded with stewed tomatoes and bell peppers.

They were still cooking in California when, five days later, with Hurricane Barry bearing down on the Gulf Coast, World Central Kitchen sent chefs to Lafayette, Louisiana, and New Orleans. In about a week, WCK prepared some 35,000 meals.

Over the last two years, in fact, there has not been a day without WCK chefs deployed somewhere—in Mozambique, Guatemala, Colombia, Venezuela, Tijuana and, this past fall, in the Bahamas after Hurricane Dorian, where WCK dished up one million meals.

Media coverage of WCK has focused on Andrés, the outspoken chef from Spain who arrived in the States at 21, after a three-year stint in Catalonia at El Bulli, which was the world’s most acclaimed restaurant before it closed in 2011. By 23, Andrés was chef at Jaleo in Washington, D.C., and now he oversees an empire of some 28 restaurants in 12 cities, including D.C.’s modernist haven Minibar, which holds two Michelin stars.

But World Central Kitchen is not just another celebrity charity project. Andrés’ goal is nothing short of a new model for disaster relief that provides better, more nutritious food for less money, all while investing in afflicted communities at the time they need it most. “I get praise more than I deserve,” Andrés told me. “Inside me is this feeling that we’ve not really achieved anything major yet. That even where we are today, it is only a platform for the things that may come ahead.”

Andrés has long been a student of the politics of hunger and disaster relief. His lessons began shortly after he arrived in Washington and volunteered at DC Central Kitchen, a nonprofit dedicated to fighting hunger by training unemployed adults to prepare meals for the homeless. Robert Egger, founder of DC Central Kitchen, became a mentor to Andrés, who went on to serve as the organization’s board chairman.

In 2010, Andrés was headlining a fancy food festival in the Cayman Islands a few days after an earthquake flattened Haiti. He went there to help, and made a discovery. “We didn’t have organizations led by cooks the same way we had rebuilding organizations led by architects or health organizations led by doctors,” Andrés said. That year, using $50,000 in prize money from the Vilcek Foundation, which raises awareness of immigrant contributions in America, Andrés founded World Central Kitchen “for cooks like me who want to join forces and feed people in moments of chaos.”

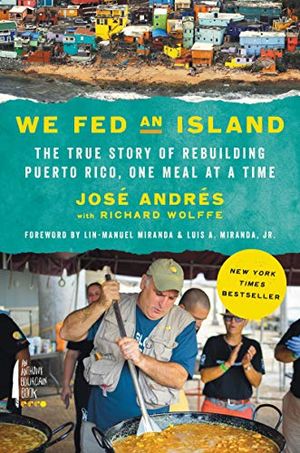

It was Andrés’ intervention in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria in 2017 that made WCK famous. The island was without power and without fuel when Andrés arrived on one of the first flights following the storm; immediately he connected with a network of chefs and purveyors. “These things I had been thinking through and developing in my brain, we knew we could do,” he said in an interview. “And we did. We went all in.” In his book about the effort, We Fed an Island, Andrés is matter-of-fact about how he bullied suppliers to extend him credit for food and used the news media to pressure the Federal Emergency Management Agency for support. He and WCK mobilized chefs, schools, distributors, truck drivers and more than 20,000 volunteers—and served 3.7 million meals over nine months.

Traditionally, feeding disaster victims has been the responsibility of the same relief organizations that provide shelter and medical care, and most of the time the food is an afterthought: meals cooked in expensive mobile kitchens or, worse, MREs, military-style Meals Ready to Eat, such as “rib-shaped barbecue flavored pork” with a shelf life of somewhere close to forever.

Andrés acknowledges that an instant meal that can be stored indefinitely without refrigeration is “an amazing accomplishment by humanity,” but says it is meant for soldiers in combat zones, not families displaced from their homes. And so World Central Kitchen strives to source food locally, and wrangles local chefs and volunteers to cook it in nearby commercial kitchens. In other words, WCK staff don’t helicopter into a disaster area and pretend to have all the answers; they leverage the community’s knowledge and resources, and provide support. Which is often cheaper. On average, a hot meal prepared by World Central Kitchen costs between $2.50 and $4—and much of that money goes to pay farmers, cooks or the guy driving the food truck. The average cost of an MRE is $8 to $10.

“People ask, José, how do you get the food?” says Nate Mook, WCK’s executive director. “He always looks at them like they’re crazy. ‘I’m a chef. That’s what I do. I get food.’ Our model is entirely different from the way it’s always worked. We’re software, not hardware.”

At a time when chefs are often associated with frivolity or decadence, Andrés uses his renown to open doors and smooth the bumpy path to change. “He is the perfect social enterprise,” says Egger. “His success in business as a world-class chef gets him in rooms that, God knows, I could never get into and he uses that to help people.”

Not that he enjoys sitting around a conference room table. “There are too many meetings and too many speeches, too much wasteful money thrown at projects when we don’t have enough boots on the ground,” he said. “Let’s get the people in the offices and meeting rooms out and making things happen.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(418x187:419x188)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/6c/666c941a-8b7f-4717-a975-4849442a1a00/joseandres_mobile.jpg)

:focal(704x266:705x267)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/52/965243a1-eda9-44d2-a776-fbb00ce39477/social_progress.png)