What the Founding Fathers’ Money Problems Can Teach Us About Bitcoin

The challenges faced by the likes of Ben Franklin have a number of parallels to today’s cryptocurrency boom

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/39/c139e61a-9766-44cd-bbd7-02f5d30988a9/apr2018_a12_prologue-wr.jpg)

If you walk into the Ketchup Premium Burger Bar in Las Vegas, tucked inside you’ll find a strange icon of today’s economy: a Coinsource ATM. Put in a few American dollars, and the ATM will quickly exchange them for Bitcoin, the newfangled digital currency, which it will place in your “digital wallet.” Want to do the reverse transaction? No problem: you can sell Bitcoin and withdraw U.S. greenbacks.

Bitcoin, as you may have heard, is poised to overturn the world of currency. That’s because it’s a form of digital cash that adherents regard as unusually robust. Bitcoin is managed by a community of thousands of “miners” and "nodes" worldwide that are running the Bitcoin software, each of them recording every single transaction that takes place. This makes Bitcoin transactions extremely hard to fake: If I send you a Bitcoin, all those Bitcoin nodes record that transaction, so you cannot later claim you didn’t receive it. Similarly, I can prove I own 100 Bitcoin because the Bitcoin network affirms this.

It’s the first global currency, in other words, that people feel secure enough to own—yet isn’t controlled by any government.

And it’s making some Bitcoin holders massively wealthy—at least on paper. “We got in early, jumped with both feet,” says Cameron Winklevoss, a high-tech entrepreneur who, with his twin brother, Tyler, bought millions of dollars of Bitcoin when a single digital coin was worth under $10. By the end of 2017, Bitcoin had soared to almost $20,000 per coin, making the Winklevosses worth $1.3 billion in the virtual dough. But Bitcoin is also wildly volatile: Mere weeks later, its value plunged in half—shaving hundreds of millions off their fortune.

It hasn’t fazed them. The Winklevoss twins, who won $65 million from Facebook in a lawsuit claiming the business was their idea, believe Bitcoin is nothing less than the next incarnation of global money. “This was something that was previously not thought possible,” Cameron says. “They thought that we need central banks, we need Visa, to validate transactions.” But Bitcoin shows that a community of people can set up a currency system themselves. It’s why Bitcoin’s earliest and most ardent fans were libertarians and anarchists who deeply distrusted government control of money. Now they had their own, under no single person or entity’s control!

Nor is Bitcoin alone. Its rise has set up an explosion of similar “cryptocurrencies”—companies and individuals who take open-source blockchain code freely available online and use it to issue their own “alt-coin.” There’s Litecoin and Ether; there are start-ups that raised tens of millions in just a few hours by issuing a coin avidly bought by fans who hope it, too, will pop like Bitcoin, making them all instant cryptomillionaires.

Though it’s hard to fix a total, according to CoinMarketCap there appear to be more than 1,500 alt-coins in existence, a global ocean of digital cash worth likely hundreds of billions. Indeed, the pace of coin-issuing is so frantic that alarmed critics argue they’re nothing but Ponzi schemes—you create a coin, talk it up and when it’s worth a bunch, sell it, leaving the value to crash for the Johnny-come-lately suckers.

So which is it? Are Bitcoin and the other alt-coins serious currencies? Can you trust something that’s summoned into being, without a government backing it?

As it turns out, this is precisely the conundrum that early Americans faced. They, too, needed to create their own currencies—and find some way to get people to trust in the scheme.

**********

Currencies are thousands of years old. For nearly as long as we’ve been trading goods, we’ve wanted some totem we can use to represent value. Ancient Mesopotamians used ingots of silver as far back as 3,000 B.C. Later Europe, too, adopted metal coins because they satisfied three things that money can do: They’re a “store of value,” a “medium of exchange” and a way of establishing a price for something. Without a currency, an economy can’t easily function, because it’s too hard to get everything you need via barter.

The first American Colonists faced a problem: They didn’t have enough currency. At first, the Colonists bought far more from Britain than they sold to it, so pretty soon the Colonists had no liquidity at all. “The mind-set was, wealth should flow from the Colonies to Britain,” says Jack Weatherford, author of The History of Money.

The History of Money

In his most widely appealing book yet, one of today's leading authors of popular anthropology looks at the intriguing history and peculiar nature of money, tracing our relationship with it from the time when primitive men exchanged cowrie shells to the imminent arrival of the all-purpose electronic cash card.

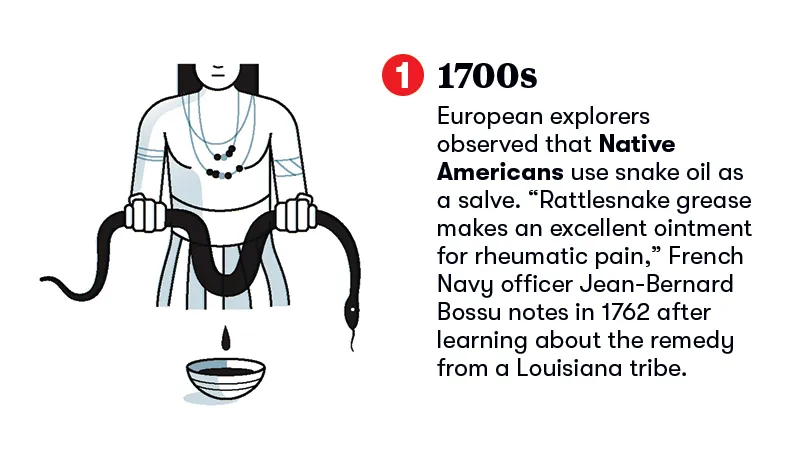

So the Colonists fashioned their own. They used tobacco, rice or Native American wampum—lavish belts of beaded shells—as a temporary currency. They also used the Spanish dollar, a silver coin that was, at the time, the most widely used currency worldwide. (The terminology stuck: This is why the government later decided to call its currency the “dollar” rather than the “pound.”)

A young Ben Franklin decided that the United States needed more. He’d noticed that whenever a town got an infusion of foreign currency, business activity suddenly boomed—because merchants had a trustworthy, liquid way to do business. Money had a magical quality: “It is Cloth to him that wants Cloth, and Corn to those that want Corn,” he wrote, in a pamphlet urging the Colonies to print their own paper money.

War is what first pushed the Colonies to print en masse. Massachusetts sold notes to the public to fund its battles in Canada in 1690, promising that citizens could later use that money to pay their taxes. Congress followed suit by printing fully $200 million in “Continental” dollars to fund its expensive revolution against Britain. Soon, though, disaster loomed: As Congress printed more and more bills, it triggered catastrophic inflation. By the end of the war, the market drove the value of a single Continental to less than a penny. All those citizens who’d traded their goods for dollars had, in effect, just transferred that wealth to the government—which had spent it on a war.

“That’s where they got the phrase, ‘not worth a Continental,’” says Sharon Ann Murphy, professor of history at Providence College and author of Other People’s Money.

Some thought it was a clever and defensible use of money-printing. “We are rich by a contrivance of our own,” as Thomas Paine wrote in 1778. Government had discovered that printing dough could get them through a rough patch.

But many Americans felt burned and deeply distrustful of government-issued bucks. Farmers and merchants were less happy with fiat currency—not backed up by silver or gold—because of how the often-inevitable inflation wreaked havoc with their trade.

This tension went all the way to the drafting of the Constitution. James Madison argued “nothing but evil” could come from “imaginary money.” If they were going to have currency, it should only be silver and gold coins—things that had real, inherent value. John Adams hotly declared that every dollar of printed, fiat money was “a cheat upon somebody.” As a result, the Constitution struck a compromise: Officially, it let the federal government mint only coins, forcing it to tether its currency to real-world value. As for the states? Well, it was OK for financial institutions in the states to issue “bank notes.” Those were essentially IOU’s: a bill that you could later redeem for real money.

As it turns out, that loophole produced an avalanche of paper money. In the years after the Revolution, banks and governments across the U.S. began avidly issuing bank notes, which were used more or less as everyday money.

Visually, the bills tried to create a sense of trustworthiness—and Americanness. The iconography commonly used eagles, including one Pennsylvania bill that showed an eagle eating the liver of Prometheus, which stood in for old Britain. They showed scenes of farming and households. The goal was to look soothing and familiar.

“You had depictions of agricultural life, of domestic life. You get portraits literally of everyday people. You got depictions of women, which you don’t have today on federal bills!” says Ellen Feingold, curator of the national numismatic collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “You got pictures of someone’s dog.” All told, there were probably 9,000 different bills issued by 1,600 different banks.

But figuring out which bill to trust was hard—a daily calculation for the average American. If you lived in New Hampshire and someone handed you a $5 bill issued by a Pennsylvania bank, should you trust it? Maybe you’d only give someone $4 worth of New Hampshire money for it, because, well, to truly redeem that bill for gold or coins you’d need to travel to Pennsylvania. The farther the provenance of the bill, the less it might be worth.

“As crazy as this sounds, this was normal for Americans,” says Steven Mihm, associate professor of history at the University of Georgia and author of A Nation of Counterfeiters. In a very real way, Americans thought daily about the philosophy of currency—what makes a bill worth something?—in a way that few modern Americans do. It makes them far more similar to those digital pioneers today, pondering the possible value of their obscure alt-coins.

A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States

"A Nation of Counterfeiters" is a trailblazing work of history, one that casts the country's capitalist roots in a startling new light. Readers will recognize the same get-rich-quick spirit that lives on in the speculative bubbles and confidence games of the twenty-first century.

**********

One thing that made it even harder to trust currency was the rampant counterfeiting. Creating fake money was so easy—and so profitable—that all the best engravers worked for the criminals. Newspapers would print columns warning readers about the latest forgeries. Yet Americans mostly shrugged and used the counterfeit bills. After all, so long as the person you were doing business with was willing to take the bill—well, why not? Fakes might be the only currency available. Keeping business moving along briskly was more important.

“Using counterfeits was a typical thing in merchants, and bars. Especially in a bar! You get a counterfeit bill and you put it back in circulation with the next inebriated customer,” says Mihm. Rather than copy existing bills, some counterfeiters would simply create their own, from an imaginary bank in a far-off U.S. state, and put it into circulation. Because how was anyone going to know that bank didn’t exist?

Banks themselves caused trouble. A nefarious banker would print bills of credit, sell them, then close up shop and steal all the wealth: “wildcatting.” A rumor that a healthy bank was in trouble would produce a “bank run”—where customers rushed to withdraw all their money in hard, real, metal coins, so many at once that the bank wouldn’t actually have the coins on hand. A bank run could destroy a local economy by making the local currency worthless. Banks, and bankers, thus became hated loci of power.

Yet the biggest currency crisis was still to come: the Civil War. To pay for the war, each side printed fantastic amounts of dough. Up North, the Union minted “greenbacks.” One cartoon mocked politicians of the time, with a printer cranking out bills while complaining: “These are the greediest fellows I ever saw...With all my exertions I cant [sic] satisfy their pocket, though I keep the Mill going day and night.”

When the North won the war, the greenback retained a decent amount of value. But the South under Jefferson Davis had printed a ton of its own currency—the “grayback”—and when it lost the war, the bills became instantly worthless. White Southerners were thus economically ruined not only by the freeing of their previously unpaid-for source of labor—the slaves—but by the collapse of their currency.

In the 1860s, the federal government passed laws establishing a national banking system. They also established the Secret Service—not to protect the president, but to fight counterfeiters. And by the late 19th century, you could wander the nation spending the American dollar more or less confidently in any state.

**********

Bitcoin—and today’s other cryptocurrencies—solve old problems of currency and create new limits on how it’s used. They cannot easily be counterfeited. The “blockchain”—that accounting of every transaction, copied over and over again in thousands of computers worldwide—makes falsifying a transaction unbelievably impractical. Many cryptocurrencies are also created to have a finite number of coins, so they can’t be devalued, producing runaway inflation. (The code for Bitcoin allows for only 21 million to be made.) So no government could pay for its military ventures by arbitrarily minting more Bitcoin.

This is precisely what the libertarian fans of the coin intended: to create a currency outside government control. When Satoshi Nakamoto, the secretive, pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin released it in 2009, he wrote an essay savagely critiquing the way politicians print money: “The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.”

Still, observers aren’t sure a currency can work when it’s backed only by the faith of people participating in it. “Historically, currencies require either that it’s based in something real, like gold, or it’s based in power, the power of the state,” as Weatherford says. If for some reason the community of people who believe in Bitcoin were to falter, its value could dissolve overnight.

Some cryptocurrency pioneers think alt-coins are thus more like penny stocks—ones that get talked up by shysters to lure in naive investors, who get fleeced. “I want a worse word than ‘speculation,’” says Billy Markus, a programmer who created a joke alt-coin called “Dogecoin,” only to watch in horror as hucksters began actively bidding it up. “It’s like gambling, but gambling with a very standard kind of predictable human emotions.”

Mihm thinks the rush toward Bitcoin illustrates that the mainstream ultimately agrees, in some way, with the libertarians and anarchists of alt-coins. People don’t trust banks and governments. “The cryptocurrencies are an interesting canary in the coal mine, showing a deeper anxiety about the future of government-issued currencies,” he says.

On the other hand, it’s possible that mainstream finance may domesticate the various alt-coins—by adopting them, and turning them into instruments of regular government-controlled economies. As Cameron Winklevoss points out, major banks and investment houses are creating their own cryptocurrencies, or setting up “exchanges” that let people trade cryptocurrencies. (He and his twin set up one such exchange themselves, Gemini.) “It’s playing out, it’s happening,” he notes. “All the major financial institutions have working groups looking at the tech.” He likens blockchain technology to the early days of the internet. “People thought, why do I need this? Then a few years later they’re like, I can’t live without my iPhone, without my Google, without my Netflix.”

Or, one day soon, without your Bitcoin ATM.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this story conflated Bitcoin mining and nodes. Mining validates Bitcoin transactions; nodes record Bitcoin transactions.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Clive_Thompson_photo_credit_is_Tom_Igoe.jpg)