A Coronavirus Spread Through U.S. Pigs in 2013. Here’s How It Was Stopped

The containment practices of outbreaks past could have lessons for modern epidemics

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/c6/6fc600db-132c-4773-be49-fc100d0b13bf/pig_farm.jpg)

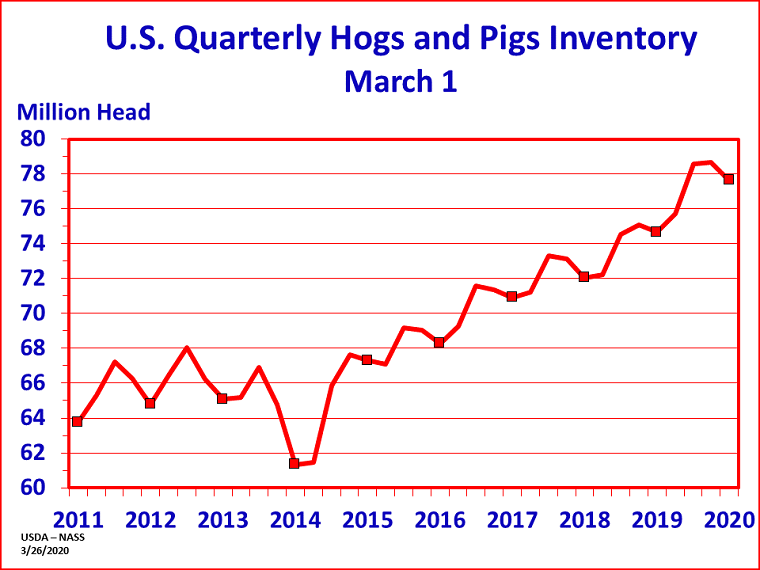

In the spring of 2013, a deadly coronavirus began to spread across the United States. Within a year it had reached 32 states, sweeping through dense populations that lacked immunity to the new pathogen. Though researchers scrambled to curb the disease, by the following spring, the epidemic claimed some 8 million lives—all of them pigs.

The pathogen responsible, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDv), poses no danger to humans. But among its hosts, pigs, the virus ravages their bodies with severe gastrointestinal disease. The 2013 outbreak killed an estimated 10 percent of the nation’s pigs in a matter of months. Struggling to make ends meet with limited supplies, pork producers pushed their prices to record highs as farmers nursed the dying and sick—most of which were newborn piglets—by the thousands.

“It was extremely devastating,” says Don Davidson, a veterinarian with the Ohio-based food company Cooper Farms. “The losses were huge. Months later … you could just see there weren’t as many pigs in market.”

By summer of 2014, the diarrheal disease had mostly petered out, partly because of a combination of increased diagnostic efforts and the growing immunity of the nation’s pig population. But perhaps the biggest factor in ending the epidemic was behavioral: a near-universal ramp-up in farms’ attention to cleaning, disinfection and isolation, says Michaela Trudeau, an animal coronavirus researcher at the University of Minnesota. These enhanced biosecurity measures “are one set of things we turn to over and over again to keep our pigs safe,” she says.

As the world battles another dangerous coronavirus, the human pathogen SARS-CoV-2, similar lessons could prove valuable once again. People aren’t pigs, and SARS-CoV-2—a respiratory virus—does not cause the same illness as PEDv. But this new coronavirus is vulnerable to many of the tactics that brought its predecessors to heel. In both cases, “it comes down to cooperation,” Trudeau says. “The more people [working to] contain it, the better off we’ll be.”

A cosmopolitan disease

The human population first discovered PEDv in the early 1970s, when veterinarians in Britain noticed pigs falling ill with bouts of watery diarrhea that couldn’t be traced back to any known pathogens. Because many cases were mild and the disease mostly spared piglets, farmers largely shrugged off the outbreaks.

Then, as the decades passed, the virus snuck across international borders and mutated. By 2010, strains emerging in China were sparking massive outbreaks that felled newborn pigs in droves.

In April of 2013, PEDv made landfall in the United States, flaring up first in Ohio and then Indiana and Iowa. Alarmed farmers and researchers ran tests for the typical spate of diarrheal microbes, yielding negative after negative. By the time PEDv was identified as the likely culprit, the pathogen had started to spread east and west. Although American veterinarians knew of the virus’ existence abroad, few had given serious thought to a PEDv cross-continental jump. American pigs had no immunity to fight off the new pathogen, and no vaccines or treatments were available.

The virus “had never made it to the U.S., and we thought it would stay that way,” says Montserrat Torremorell, an animal health expert at the University of Minnesota. “We weren’t ready.”

Likely stemming from the same ancestor that had yielded China’s deadly strains, the American variant of the virus proved a formidable foe. “It’s extremely infectious” in low doses, says Davidson, who explains he once heard that “the eraser on top of a No. 2 pencil could hold enough PED virus to infect every pig in the United States.”

Once swallowed by an unsuspecting piglet, the pathogen would travel to the gut and infect and destroy the finger-like nutrient-absorbing projections called villi on the walls of the small intestine. Newborn piglets were plagued with intense bouts of diarrhea, driving extreme dehydration that proved lethal within a few days of infection: On many farms, the death rates in the youngest swine “were just about 100 percent,” Davidson says.

Though older pigs remained mostly resilient to the disease’s most severe effects, they weren’t immune to infection. Even in the absence of symptoms, they shed and spread the virus through their feces, seeding new outbreaks as unsuspecting farmers shipped their swine stocks nationwide.

“This industry is structured in such a way that pigs move, and not just by a few miles,” Torremorell says. Domesticated pigs are, not unlike humans, a fairly cosmopolitan group. In a single lifetime, a pig may make several trips of a thousand miles or more, such as when it’s ready for sale or slaughter.

Humans, too, played a major role in transmission. While PEDv can’t infect people, the pathogen used them as its oblivious chauffeurs, hitching rides to new swine hosts as farmers, feed suppliers and veterinarians traveled from place to place. Hardy enough to persist for several days outside the pig body, the virus clung to clothes and glommed onto the soles of shoes. It planted itself onto equipment and coated the insides of trailers and trucks.

Worst of all may have been the virus’ ability to fester for weeks in feed, giving the pathogen a straight shot into the guts of its hosts. “Feed ingredients have unique access to our pigs,” says Megan Niederwerder, a veterinary virologist at Kansas State University. “That definitely was not at the forefront of our minds.”

A wake-up call

The outbreak moved at “eye opening” speed, Davidson says. “Just about everybody got it. I don’t know any large farm systems that didn’t.”

In the absence of reliable, widely available medical interventions, farmers and veterinarians turned most of their focus to diagnosis and containment. “We already had pretty solid biosecurity protocols on farms,” Trudeau says. “But this really made us take a step back and think, because it was traveling so easily which we hadn’t necessarily seen with other viruses before.”

Suddenly, Trudeau says, everything moving to and from a farm was subject to intense scrutiny. No surface was too small or too hidden to escape the reach of a microscopic virus. All pigs and people had to be treated as potential vectors for disease.

“Farmers effectively shut down their farms,” says Scott Kenney, an animal coronavirus researcher at Ohio State University. “Friends from other farms weren’t able to come in, sales reps weren’t allowed to come in. And the people who did had to change their clothes before going into farms.”

Trudeau says that most places that dealt with pigs already had a “shower in, shower out” policy in place that required visitors to remove their clothing, wash off with soap and water, and don a clean outfit before making any contact with animals. Exiting the building then required the same procedure in reverse. “It’s very extensive,” she says. “Nothing is coming onto the farm that hasn’t been washed.”

In the pre-PEDv era, not everyone was vigilant about following showering guidelines, Trudeau says. By necessity, the outbreak changed that, says Marie Culhane, a veterinarian at the University of Minnesota. “It’s not business as usual during an outbreak.”

Farmers, feed distributors and transport personnel became ardent disinfectors, regularly sterilizing frequently contacted surfaces, including equipment. Because the insides of trucks were especially difficult to clean, drivers ferrying supplies no longer left their vehicles, asking farm personnel to do the unloading themselves. And any individuals who had recently spent time in a heavily pig-populated place, like a county fair, would wait at least 72 hours before stepping onto a swine establishment—a form of self-isolation.

Importantly, farmers put these measures in place without waiting for their pigs to show symptoms, Torremorell says. “When that virus infects older animals, they can be shedding continuously and have no clinical signs. You just don’t know.”

The payoff wasn’t instantaneous. But slowly the epidemic began to wane, and by the fall of 2014, PEDv had finally loosened its grip. The virus has reappeared in the years since, flickering briefly in pig populations before being stamped out. Many of the pigs that survived the first epidemic became immune to further infection. But farmers are also much more savvy nowadays. Whenever the pathogen appears, “they basically shut down things right away, like going into lockdown,” Torremorell says. “When that happens, there’s not as much spread.”

The other coronavirus

In the absence of an effective, long-lasting PEDv vaccine—something that still eludes veterinarians—control of epidemics “depends critically on high biosecurity,” says Qiuhong Wang, an animal coronavirus expert at Ohio State University.

While SARS-CoV-2 and PEDv belong to the same family, the two viruses target different hosts and different parts of the body, and shouldn’t be considered interchangeable in any respects. But in broad strokes, containing an infectious disease hinges on a common set of principles that promotes awareness about transmission, minimizes contamination of surfaces and materials, and champions the effectiveness of practicing good hygiene, Torremorell says.

For humans, following that strategy includes adhering to physical distancing measures, frequent cleaning and disinfecting and taking precautions in the absence of symptoms, Trudeau says. What’s more, adopting these tactics now could help prepare the population for its next outbreak.

“We learned lots on the pig side about being better prepared,” Davidson says. “Behavioral change is hard. But it works.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)