That Time When Custer Stole a Horse

The theft of a prize-winning stallion gave the famous general a glimpse of a future that could have been

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/2f/ef2fe458-a45b-45e0-960b-00a6fcf17996/custer_smithsonian.jpg)

On April 25, 1865, a man named Junius Garland watched a group of Union cavalrymen ride out of the woods near Clarksville, Virginia, and approach. Garland, a skilled groom, tended to a beautiful thoroughbred stallion: more than 15 hands high; solid bay with black legs, mane and pert tail; and a proud, erect head. That’s Don Juan, the soldiers said, referring to the horse. We’ve been looking for him for days.

Garland was illiterate, having spent his life in slavery, but he wasn’t stupid. He had been Don Juan’s groom for the past few years, and he knew the horse’s value. In the days following Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, word had spread that Union troops were seizing good horses. Garland had hidden Don Juan at a farm in the woods on behalf of its owners, but another freedman told the soldiers where to find it.

The troopers harnessed Don Juan to a sulky, a light two-wheeled cart with little more than a driver’s seat. They demanded one more thing: Don Juan’s pedigree, printed in a handbill. They took it and drove the horse away.

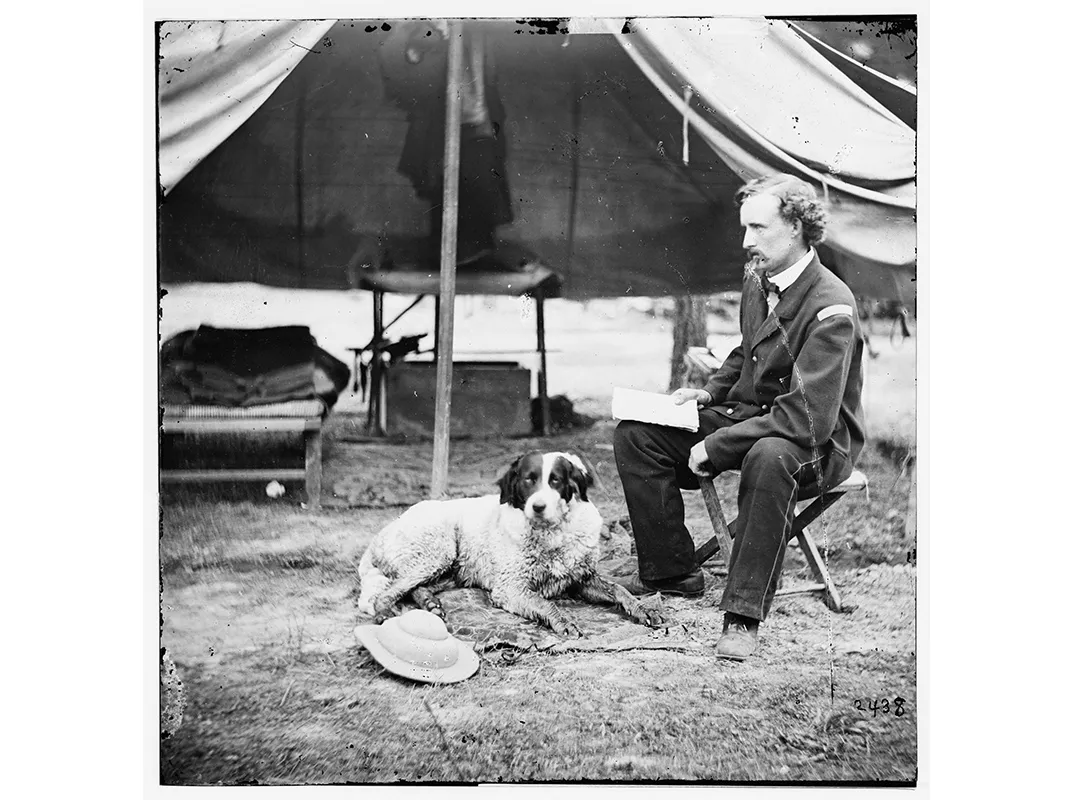

Two weeks later, Dr. C.W.P. Brock visited the camp of the 3rd Cavalry Division, about five miles from Richmond. His horse had been impounded, too, and he went to see the division commander, Maj. Gen. George A. Custer, to ask for it. Custer received him, but he was distracted, excited. Have you heard of Don Juan? he asked Brock. Have you ever seen him? Brock said he only knew the animal’s reputation as “a thoroughbred race horse.” Custer and an unnamed lieutenant took Brock to a stable to see the famous stallion, which was “being curried down,” Brock recalled. “Gen. Custer said that that was the horse, that he had him, and that he also had his pedigree.”

For 150 years, it has been public knowledge that Custer owned Don Juan, but not how he acquired it. His many biographers have written that Union troops seized it during a wartime campaign, as they confiscated every horse in Rebel territory; that was Custer’s own explanation. Until now, the truth has remained hidden in the open, told in correspondence and affidavits archived in the library of the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument and the National Archives that have aroused little curiosity among those biographers. But the truth raises important questions about the man and his place in American history.

And 16 days after Lee’s surrender, ten days after Lincoln’s death by assassination, with all fighting at an end east of the Mississippi River, George Armstrong Custer stole a horse.

During the Civil War, Custer had fought courageously and commanded skillfully—but now, with the war over, he used his military authority to take what was not his, for no official purpose. Was it greed that corrupted him? A passion for fine horseflesh—common to most Americans in 1865, but particularly intense in this cavalryman? Was it power—the fact that he could take it? As the military historian John Keegan memorably wrote, “Generalship is bad for people.” Custer was only 25, an age more commonly associated with selfishness than self-reflection, and perhaps that explains it. But the theft was not impulsive. It had required investigation, planning and henchmen. It may help explain his self-destructive actions in the months and years that followed.

More than that, the story of Don Juan reveals a glimpse of Custer as a very different figure from the familiar Western soldier on a dead-end march to the Little Bighorn—different even from the Boy General of the Civil War, whose success as a Union cavalry commander was exceeded only by his flamboyance. It shows him as a man on a frontier in time, living on the crest of a great transformation of American society. In the Civil War and its aftermath, the nation we know today began to emerge, hotly disputed but clearly recognizable, with a corporate economy, industrial technology, national media, strong central government and civil rights laws. It supplanted an earlier America that was more romantic, individualistic and informal—and had enslaved some four million people based on their race. Custer pushed this change forward in every aspect of his surprisingly diverse career, yet he never adapted to the very modernity he helped to create. This was the secret to his contemporary fame and notoriety. His fellow citizens were divided and ambivalent over the destruction and remaking of their world; to them, Custer represented the Republic’s youth, the nation as it had been and never would be again. Like much of the public, he held to old virtues but thrilled to new possibilities. Yet whenever he tried to capitalize on the new America, he failed—beginning with a stolen horse named Don Juan.

**********

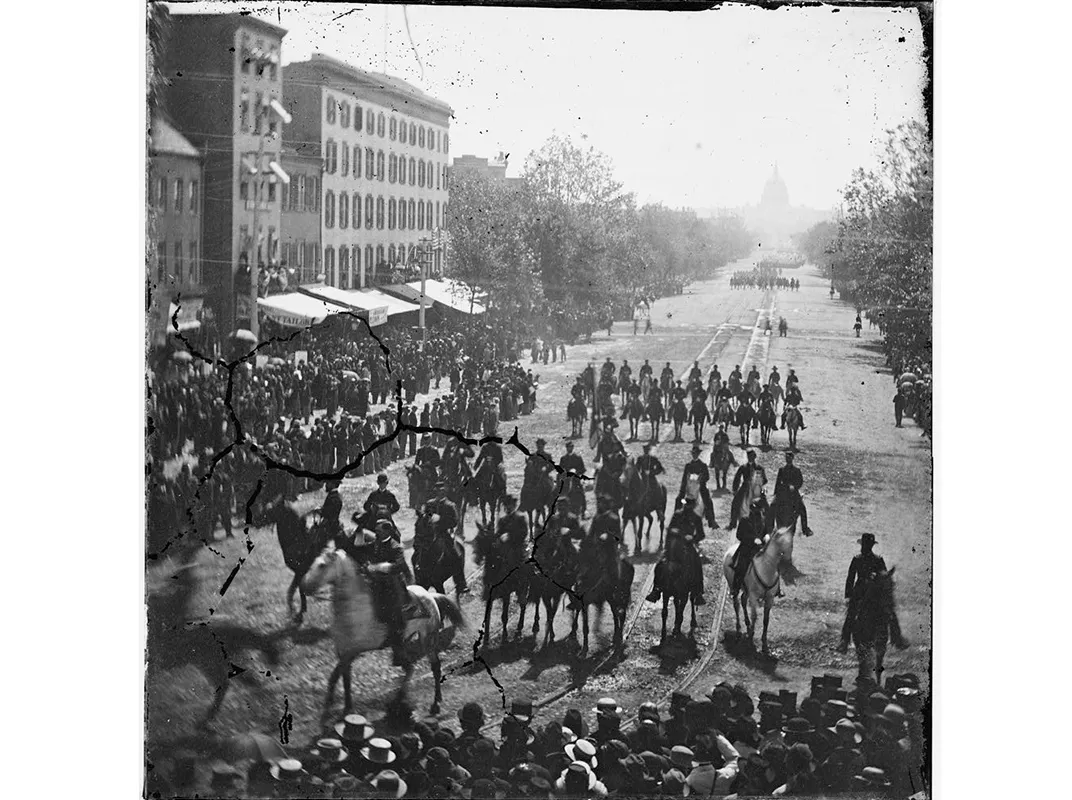

Don Juan’s debut with Custer in the saddle stands as an iconic moment in his life, for it was his apotheosis as a national hero. But as with so many of Custer’s iconic moments, controversy envelops it, for all the wrong reasons. It came during the two-day Grand Review, the Union armies’ triumphal march through Washington, D.C. to celebrate their victory in the Civil War. Beginning on May 23, tens of thousands of spectators crowded toward Pennsylvania Avenue for the great parade. A reviewing stand had been constructed at the White House for the commanding generals, key senators and congressmen (including Custer’s sponsor, Senator Zachariah Chandler), foreign diplomats and Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson. Flags and bunting hung everywhere. The Capitol displayed a huge banner reading, “The only national debt we cannot pay is the debt we owe to the victorious Union soldiers.”

The first day of the parade belonged to the Army of the Potomac. The legions of veterans formed up east of the Capitol, the men dressed as they had in the field, though now they were clean and tidy. Custer wore his wide-brimmed slouch hat over his long curly hair and the proper uniform of a major general. Sometime after nine o’clock in the morning the procession started. Gen. George G. Meade led the way, followed by the general staff and the leadership of the Cavalry Corps. The march of units began, led by the 3rd Cavalry Division, each man in a red necktie.

Bands marched ahead of each brigade, filling the air with brass notes. Battle flags, tattered by bullets, embroidered with the names of victories, rose on wooden staffs, a moving grove of memory. As the procession wound around the north side of the Capitol, it passed by thousands of schoolchildren who burst into song—the girls in white dresses, the boys in blue jackets. Down the wide avenue the horsemen rode, shoulder to shoulder, curb to curb.

Custer led them. His sword rested loosely on his lap and over his left arm, with which he held the reins. His horse seemed “restive and, at times, ungovernable,” noted a reporter for the Chicago Tribune. It was Don Juan, the powerful, beautiful, stolen stallion. Custer had had only a month with the horse, which had been raised solely to sprint down a track and to mate. Neither capacity particularly suited it to the cacophony and distractions of the Grand Review.

The crowd roared for Custer—the champion, the hero, gallantry incarnate. Women threw him flowers. As he approached the reviewing stand, a young lady hurled a wreath of blossoms at him. He caught it with his free hand—and Don Juan panicked. “His charger took fright, reared, plunged and dashed away with his rider at an almost breakneck speed,” a reporter wrote. Custer’s hat flew off. His sword clattered to the street. “The whole affair was witnessed by thousands of spectators, who were enchained breathlessly by the thrilling event, and, for a time, the perilous position of the brave officer,” the Tribune reported. He held the wreath in his right hand as he fought for control with the reins in his left. Finally he yanked Don Juan to a halt, “to the great relief of the excited audience, who gave the gallant general three cheers,” the New York Tribune’s reporter wrote. “As he rode back to the head of his column,” the Chicago Tribune reported, “round upon round of hearty applause greeted him, the reviewing officers joining in.”

To the Harrisburg Weekly Patriot & Union, the incident said something about the mismatch of the man and the times. His ride on the runaway horse was “like the charge of a Sioux chieftain,” the newspaper stated. The cheers when he regained control were “the involuntary homage of the every-day heart to the man of romance. Gen. Custar [sic] should have lived in a less sordid age.”

It was a splendid display of horsemanship, but also an embarrassing break in decorum. An orderly had to fetch his hat and sword off the street. A suspicion arose that Custer had staged the incident to attract attention and win the crowd’s approval; some claimed that such an excellent horseman would never have lost control of his mount in a simple parade. But such arguments miss another, simpler explanation for Don Juan’s flight—the fact that it was another man’s property, ill at ease with a strange hand on the reins. Custer sat astride his sin, and it had nearly proved too much for him.

**********

“A man who lies to himself is often the first to take offense,” Dostoevsky wrote in The Brothers Karamazov. Lying to oneself is a nearly universal human trait, to one degree or another. But some consciousness of the truth usually lurks; reminders make the liar brittle and defensive.

Richard Gaines pursued Custer’s lie with the truth. He was the principal owner of Don Juan. A resident of Charlotte County, Virginia, he had purchased the horse for $800 in 1860 and taken great care of it through the hard years of war, and now estimated its value at $10,000. The very day of the Grand Review, Gaines took affidavits from himself, former slave Junius Garland and Dr. C.W.P. Brock to the War Department, which was receptive. “The government stalls here were unsuccessfully searched,” the Washington Star reported, “and the man finally ascertained that his horse had gone to New Orleans with the General. The disconsolate owner follows immediately.”

Custer could follow his pursuer’s progress in the newspapers, which traced the hunt for the famous Don Juan. He had left the horse in his adopted hometown of Monroe, Michigan, where it was safe for the time being. Technically it still belonged to the Army, but Custer arranged for a board of officers to assess its value at $125, which he paid on July 1, 1865. And he began to claim that the horse had been captured during one of Gen. Philip Sheridan’s cavalry raids. “I expected the former owner would make an effort to recover the horse, he being so valuable,” Custer wrote to his father-in-law, Judge Daniel Bacon. “He is the most valuable horse ever introduced into Mich....I hope to get ($10,000) ten thousand for him.” He asked Bacon not to mention the absurdly low purchase price and added that he had “a complete history of the horse.”

He didn’t explain how he would happen to have the pedigree if he had captured Don Juan in the midst of a campaign. It was a conundrum. The pedigree was key to the sale price—Custer’s one great chance at profiting from the war. But his possession of it undermined his alibi; it implicated him in precisely the theft the owner alleged.

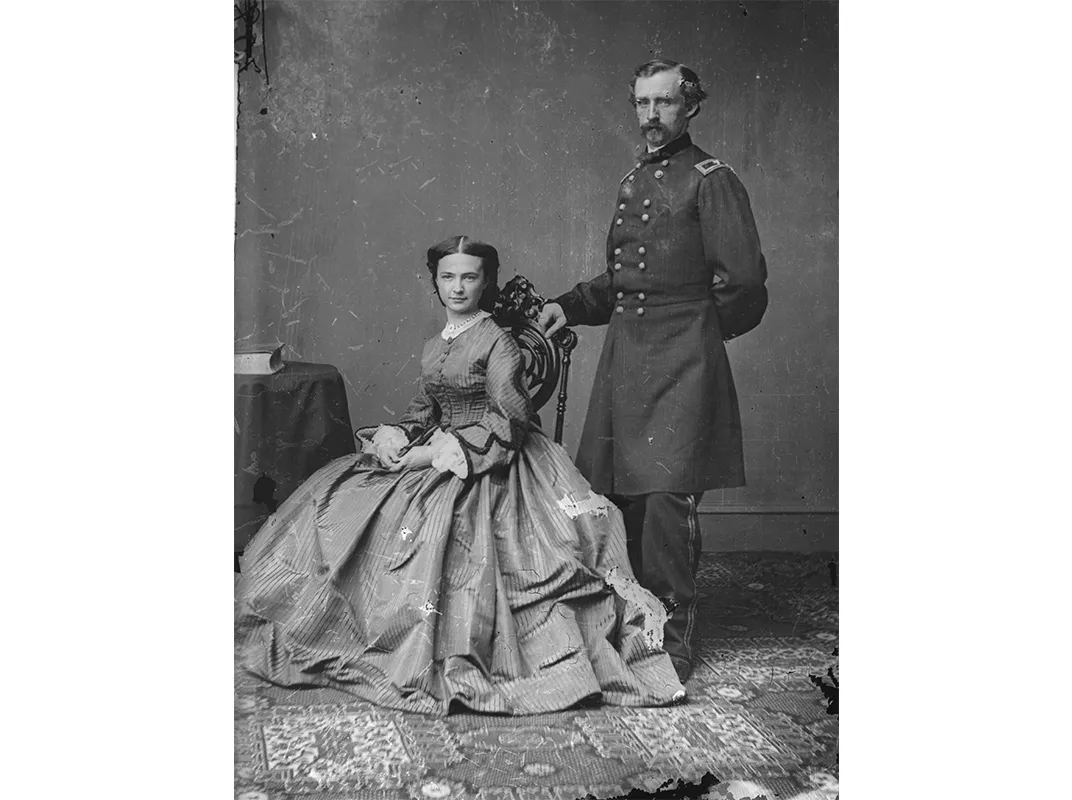

Custer had gone to Monroe immediately after the Grand Review, together with his wife, Libbie, and Eliza Brown, who had escaped slavery and become their cook and household manager. They soon departed for Louisiana. As June turned into July, they lingered in the town of Alexandria, where Custer organized a cavalry division for a march into Texas, still unoccupied by Union troops. All the while Gaines pressed his claim to Don Juan. The matter rose to the attention of General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant, who sent a direct order to Sheridan that Custer must deliver up the horse. But Sheridan put him off, repeating Custer’s defense. “At the time the horse was taken I had given orders to take horses wherever found in the country through which I was then passing,” Sheridan told Grant. “If this horse is returned so should every horse taken be returned.” Sheridan relied on Custer more than on any other subordinate; he may have accepted the alibi without question, or he may have backed Custer to protect him, right or wrong. Whatever he thought, he did not try to determine the truth. As the pressure mounted, Custer’s protector was now implicated in his lie.

It may be no coincidence that Custer’s weeks in Louisiana and his march into Texas marked a period of failure as a commander. He led five regiments of troops who had never served under him in combat—volunteers who wished to go home, now that the war was over, and resented being kept under arms. Still worse, the Army’s supply system failed, delivering almost inedible rations, such as hogs’ jowls complete with teeth and vermin-infested hardtack. Eager to placate Southern civilians, Custer attempted to suppress foraging by his troops through such punishments as flogging and head-shaving, and put one officer through a mock execution after the man circulated a petition complaining about his regimental commander. Rumors circulated of assassination plots by his men. Grant ordered Sheridan to dismiss Custer, but again Sheridan shielded his protégé. Custer even had to put down a mutiny by homesick troops in the 3rd Michigan Cavalry, which was kept in service as other volunteer regiments disbanded.

On January 27, 1866, with the Texas operation winding down, Custer received orders to report to Washington. Mustered out of the U.S. Volunteers, the temporary force created for the duration of the Civil War, he reverted to his permanent Regular Army rank of captain and returned to the East.

**********

With the future in doubt, Custer went to New York as his wife tended to her ailing father in Michigan. He lodged at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, a vast edifice opposite Madison Square with a staff of 400—“a larger and handsomer building than Buckingham Palace,” as the London Times called it in 1860. It pioneered such innovations as private bathrooms and the passenger elevator. He told Libbie that he socialized with Senator Chandler and his wife, visited the actress Maggie Mitchell, looked at paintings, attended the theater, shopped at A.T. Stewart’s famous department store “and enjoyed a drive on the Harlem Lane and the famous Bloomingdale Road,” the broad thoroughfares of rural upper Manhattan where Cornelius Vanderbilt and other wealthy men raced their expensive trotting horses.

The politically influential men of Wall Street cultivated Custer. They took him to eat at the Manhattan Club, for example. Located in a palatial building on Fifth Avenue at 15th Street, its rooms decorated with marble and hardwood paneling, the club was organized in 1865 by a group of Democratic financiers, including August Belmont and Samuel L.M. Barlow, Augustus Schell and Schell’s partner Horace Clark—Vanderbilt’s son-in-law and a former congressman who had opposed the expansion of slavery into Kansas before the war. The Manhattan Club served as headquarters for this faction of wealthy “silk-stocking” Democrats, who battled William Tweed for control of Tammany Hall, the organization that dominated the city. They provided national leadership for a party struggling with its reputation for disloyalty. And like Custer, they strongly supported President Johnson, who opposed any attempt to extend citizenship and civil rights to African-Americans.

“Oh, these New York people are so kind to me,” Custer wrote to Libbie. Barlow invited him to a reception at his house one Sunday evening, where he mingled with Paul Morphy, the great chess prodigy of the era, along with rich and famous men. “I would like to become wealthy in order to make my permanent home here. They say I must not leave the army until I am ready to settle here.”

Custer’s words contradict his image as a man of the frontier. He had that peculiar susceptibility of the rural, Midwestern, ambitious boy for the cosmopolitan center, for the culture and intensity of New York—especially when it welcomed him. He saw himself depicted in a painting of Union war heroes. Escorted to Wall Street, he attended a session of the stock exchange. The brokers gave him six cheers, and he made a few remarks from the president’s chair. His new friends hosted a breakfast for him that included the lawyer and Democratic leader Charles O’Conor, the poet William Cullen Bryant and the historian and diplomat George Bancroft. At the home of John Jacob Astor III he socialized with Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, the Union cavalry commander who had secured Custer’s promotion at the age of 23 to brigadier general of volunteers. And he almost certainly visited George McClellan, the controversial former general and Democratic presidential candidate, whom Custer had once served as an aide.

Custer’s friends invited him to take part in the new craze for masked balls at the Academy of Music, “New York’s sanctum sanctorum of high culture,” as two historians of the city wrote. “Nouveau riche Wall Street brokers in fancy dress rubbed elbows and much else with the city’s assembled demimondaines, attired in costumes that exposed much, if not all, of their persons. As the champagne flowed, modesty was abandoned and the parties escalated to Mardi Gras levels.” Custer attended one such “Bal Masqué” at the Academy of Music on April 14. He dressed as the devil, with red silk tights, black velvet cape trimmed with gold lace, and a black silk mask. Thomas Nast included Custer in a drawing of the ball for Harper’s Weekly, surrounding it with political caricatures, including one of Johnson vetoing a bill intended to extend the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Amid this attention, Custer grew callously self-indulgent. He wrote to Libbie that he and old West Point friends visited “pretty-girl-waitress saloons. We also had considerable sport with females we met on the street—‘Nymphes du Pavé’ they are called.” He added, “Sport alone was our object. At no time did I forget you.” His words were hardly reassuring; his descriptions of alluring women seemed a deliberate provocation, especially since Libbie remained with her ailing father. At one party, he wrote, he sat on a sofa next to a baroness in a very low-cut satin dress. “I have not seen such sights since I was weaned.” The experience did not make his “passions rise, nor nuthin else,” but he added: “What I saw went far to convince me that a Baroness is formed very much like all other persons of the same sex.”

One day he went to a clairvoyant with his fellow general Wesley Merritt and some “girls” whom he did not name to Libbie. A fad for spiritualism had grown in America ever since two young women claimed in 1848 to be able to communicate with a spirit through knocking sounds. With the great loss of life during the war, many survivors sought to contact the dead; even some intellectuals took clairvoyants and mediums seriously. “I was told many wonderful things, among others the year I was sick with typhoid fever, the year I was married, the year I was appointed to West Point, also the year I was promoted to Brig Genl. You were described accurately,” Custer wrote to Libbie. The woman said he would have four children; the first would die young. He had had narrow escapes from death, but would live to old age and die of natural causes. She also said, Custer reported, “I was always fortunate since the hour of my birth and always would be.” The group found her so spooky that the women refused to participate.

The clairvoyant also said “I was thinking of changing my business and thought of engaging in one of two things, Railroading or Mining.” Custer added, “(Strictly true.)” Money and politics filled his mind as he considered his future path. As he had said, he would have to make a great deal to live in New York, home to the key financial markets and Democratic leaders. He labored over the new race history and pedigree for Don Juan, citing horse-racing publications to replace the implicating original. In Washington he talked with Grant about taking a year’s leave of absence to fight for Benito Juárez in his revolution against France’s puppet emperor in Mexico, Maximilian I, in return for a promised $10,000.

Grant wrote a letter of recommendation, though he interposed Sheridan between them: Custer “rendered such distinguished service as a cavalry officer during the war. There was no officer in that branch of service who had the confidence of Gen. Sheridan to a greater degree than Gen. C. and there is no officer in whose judgment I have greater faith than in Sheridan’s.” Then, as if he realized what he was doing, he added, “Please understand that I mean by this to endorse Gen. Custer to a high degree.”

He did not go to Mexico. Secretary of State William Seward, wary of any U.S. involvement in another war, prevented it. But Custer had another means of securing $10,000. He took Don Juan to the 1866 Michigan state fair to build interest in the stallion. After the last horse race on June 23, he rode Don Juan “at full speed past the stand, the horse displaying great speed and power,” the Chicago Tribune reported. “His appearance was greeted with tremendous applause.” Judges awarded Don Juan first prize over six thoroughbred rivals.

With this rousing appearance, national press attention and the recreated pedigree, Custer now felt certain that he could sell the horse for its full value.

One month later Don Juan died of a burst blood vessel. Custer was left with nothing.

**********

It would be too much to say that Don Juan provides the key to decoding Custer’s postwar life, or explains his death at the Little Bighorn ten years later. But the horse’s theft marked a troubling departure in Custer’s life, and its death closed off a range of alternate futures. Lee scarcely had surrendered at Appomattox Court House before Custer gave in to his self-indulgent, self-destructive tendencies. After risking everything in the war, he did not seem to realize how much he risked in claiming a reward. He entered into a difficult assignment in Texas with the general-in-chief insisting upon his guilt and demanding that he surrender his prize.

As always when challenged, he grew brittle and defensive. He questioned his career in the Army as New York teased his appetite for women, money and power. He envisioned a Custer who might never wear buckskins, never shoot a bison, never lead the 7th Cavalry against Cheyennes and Lakotas. He revealed aspects of himself that remain unknown to many Americans—his taste for luxury, his attraction to urban sophistication, his political partisanship. When Don Juan died, though, Custer’s civilian future disappeared.

With few options, Custer remained in the Army. He took Libbie to Fort Riley, Kansas, in the fall of 1866, following orders to report for duty as lieutenant colonel of the 7th Cavalry. He and Libbie later professed his devotion to the military and love of the outdoor life, but he struggled to re-invent himself as a frontier soldier. His self-indulgence continued through his first year in Kansas. He rode off from his column in the field to hunt a bison, then accidentally shot his own horse dead. He abandoned his assigned duties (and two of his men who had been gravely wounded in an ambush) in order to see Libbie, earning a court-martial, conviction and suspension.

He eventually returned to duty and regained both his footing and celebrity. Over the years he tested alternate careers, on Wall Street, in politics, as a writer or speaker. None of them worked well enough for him to leave the Army. And controversy always surrounded him, as it had since he sent a squad of men to search for Don Juan.

Custer's Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America