When Dorman B.E. Kent, a historian and businessman from Montpelier, Vermont, contracted influenza in fall 1918, he chronicled his symptoms in vivid detail. Writing in his journal, the 42-year-old described waking up with a “high fever,” “an awful headache” and a stomach bug.

“Tried to get Dr. Watson in the morning but he couldn’t come,” Kent added. Instead, the physician advised his patient to place greased cloths and a hot water bottle around his throat and chest.

“Took a seidlitz powder”—similar to Alka-Seltzer—“about 10:00 and threw it up soon so then took two tablespoons of castor oil,” Kent wrote. “Then the movements began and I spent a good part of the time at the seat.”

The Vermont historian’s account, housed at the state’s historical society, is one of countless diaries and letters penned during the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed an estimated 50 to 100 million people in just 15 months. With historians and organizations urging members of the public to keep journals of their own amid the COVID-19 pandemic, these century-old musings represent not only invaluable historical resources, but sources of inspiration or even diversion.

“History may often appear to our students as something that happens to other people,” writes Civil War historian and high school educator Kevin M. Levin on his blog, “but the present moment offers a unique opportunity for them to create their own historical record.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/15/57152fc9-2137-4b03-badb-dc57f6851f31/gettyimages-108882650.jpg)

The work of a historian often involves poring through pages upon pages of primary source documents like diaries—a fact that puts these researchers in a position to offer helpful advice on how prospective pandemic journalers might want to get started.

First and foremost, suggests Lora Vogt of the National WWI Museum and Memorial, “Just write,” giving yourself the freedom to describe “what you’re actually interested in, whether that’s your emotions, [the] media or whatever it is that you’re watching on Netflix.”

Nancy Bristow, author of American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds Of The 1918 Influenza Epidemic, advises writers to include specific details that demonstrate how “they fit into the world and … the pandemic itself,” from demographic information to assessment of the virus’ impact in both the public and personal spheres. Examples of relevant topics include the economy; political messaging; level of trust in the government and media; and discussion of “what’s happening in terms of relationships with family and friends, neighbors and colleagues.”

Other considerations include choosing a medium that will ensure the journal’s longevity (try printing out entries written via an electronic journaling app like Day One, Penzu or Journey rather than counting on Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms’ staying power, says Vogt) and defying the sense of pressure associated with the need to document life during a “historic moment” by simply writing what comes naturally.

Journaling “shouldn’t be forced,” says Levin. “There are no rules. It’s really a matter of what you take to be important.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/f0/ecf0cf5d-9783-4232-a710-4052e283574e/800px-spanish_flu_in_1918_police_officers_in_masks_seattle_police_department_detail_from-_165-ww-269b-25-police-l_cropped.jpg)

If all else fails, look to the past: specifically, the nine century-old missives featured below. Though much has changed since 1918, the sentiments shared in writings from this earlier pandemic are likely to resonate with modern readers—and, in doing so, perhaps offer a jumping-off point for those navigating similar situations today.

Many of these journalers opted to dedicate space to seemingly mundane musings: descriptions of the weather, for instance, or gossip shared by friends. That these quotidian topics still manage to hold our attention 100 years later is a testament to the value of writing organically.

State historical societies are among the most prominent record-keepers of everyday people’s journals and correspondence, often undertaking the painstaking tasks of transcribing and digitizing handwritten documents. The quotes featured here—drawn in large part from local organizations’ collections—are reproduced faithfully, with no adjustments for misspelling or modern usage.

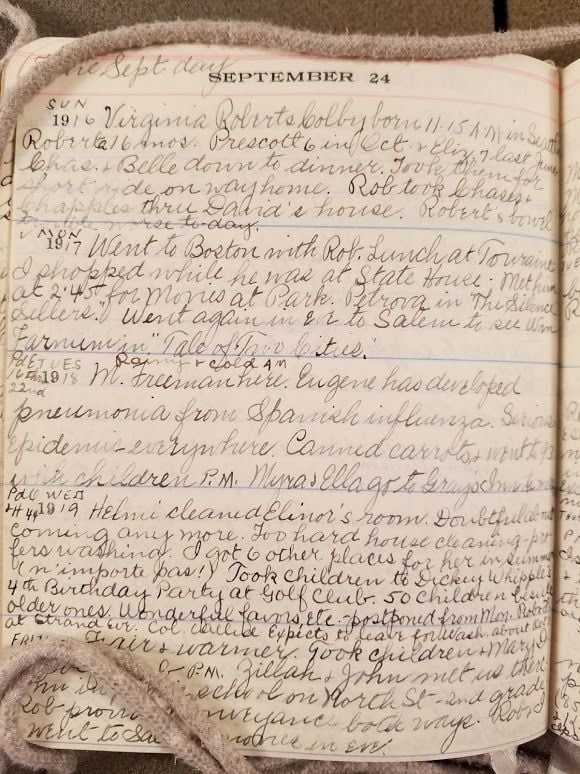

Edith Coffin (Colby) Mahoney

From the Massachusetts Historical Society

Between 1906 and 1920, Edith Coffin (Colby) Mahoney of Salem, Massachusetts, kept “three line-a-day diaries” featuring snippets from her busy schedule of socializing, shopping and managing the household. Most entries are fairly repetitive, offering a simple record of what Mahoney did and when, but, on September 22, 1918, she shifted focus to reflect the pandemic sweeping across the United States.

Fair & cold. Pa and Frank here to dinner just back from Jefferson Highlands. Rob played golf with Dr. Ferguson and Mr. Warren. Eugene F. went to the hospital Fri. with Spanish influenza. 1500 cases in Salem. Bradstreet Parker died of it yesterday. 21 yrs old.

Four days later, Mahoney reported that Eugene had succumbed to influenza. “Several thousand cases in the city with a great shortage of nurses and doctors,” she added. “Theatres, churches, gatherings of everykind stopped.”

Mahoney’s husband, Rob, was scheduled to serve as a pallbearer at Eugene’s September 28 funeral, but came down with the flu himself and landed “in bed all day with high fever, bound up head and aching eye balls.”

By September 29—a “beautiful, mild day,” according to Mahoney—Rob was “very much better,” complaining only of a “husky throat.” The broader picture, however, remained bleak. Another acquaintance, 37-year-old James Tierney, had also died of the flu, and as the journal’s author noted, “Dr says there is no sign of epidemic abating.”

Franklin Martin

From the National Library of Medicine, via research by Nancy Bristow

In January 1919, physician Franklin Martin fell ill while traveling home from a postwar tour of Europe. His record of this experience, written in a journal he kept for his wife, Isabelle, offers a colorful portrait of influenza’s physical toll.

Soon after feeling “chilly all day,” Martin developed a 105-degree fever.

About 12 o'clock I began to feel hot. I was so feverish I was afraid I would ignite the clothing. I had a cough that tore my very innards out when I could not suppress it. It was dark; I surely had pneumonia and I never was so forlorn and uncomfortable in my life. … Then I found that I was breaking into a deluge of perspiration and while I should have been more comfortable I was more miserable than ever.

Added the doctor, “When the light did finally come I was some specimen of misery—couldn't breathe without an excruciating cough and there was no hope in me.”

Martin’s writing differs from that of many men, says Bristow, in its expression of vulnerability. Typically, the historian explains, men exchanging correspondence with each other are “really making this effort to be very brave, … always apologizing for being sick and finding out how quickly they’ll be back at work, or [saying] that they’re never going to get sick, that they’re not going to be a victim of this.”

The physician’s journal, with its “blow-by-blow [treatment] of what it was like to actually get sick,” represents a “really unusually profound” and “visceral” point of view, according to Bristow.

Violet Harris

Violet Harris was 15 years old when the influenza epidemic struck her hometown of Seattle. Her high school diaries, recounted by grandniece Elizabeth Weise in a recent USA Today article, initially reflect a childlike naivete. On October 15, 1918, for example, Harris gleefully reported:

It was announced in the papers tonight that all churches, shows and schools would be closed until further notice, to prevent Spanish influenza from spreading. Good idea? I’ll say it is! So will every other school kid, I calculate. … The only cloud in my sky is that the [School] Board will add the missed days on to the end of the term.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/5b/405ba1cc-0773-429a-8c46-18f0ce919bc2/gettyimages-108882923.jpg)

Before long, however, the enormity of the situation sank in. The teenager’s best friend, Rena, became so sick she “could hardly walk.” When Rena recovered, Harris asked her “what it felt like to have the influenza, and she said, ‘Don’t get it.’”

Six weeks after Seattle banned all public gatherings, authorities lifted restrictions, and life returned to a semblance of normal. So, too, did Harris’ tone of witty irreverence. Writing on November 12, she said:

The ban was lifted to-day. No more .... masks. Everything open too. 'The Romance of Tarzan' is on at the Coliseum [movie theater] as it was about 6 weeks ago. I’d like to see it awfully. .... School opens this week—Thursday! Did you ever? As if they couldn’t have waited till Monday!

N. Roy Grist

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/d2/30d2ddae-2083-48b5-9d9d-f6b0f10f432c/base_hospital_camp_devens.jpg)

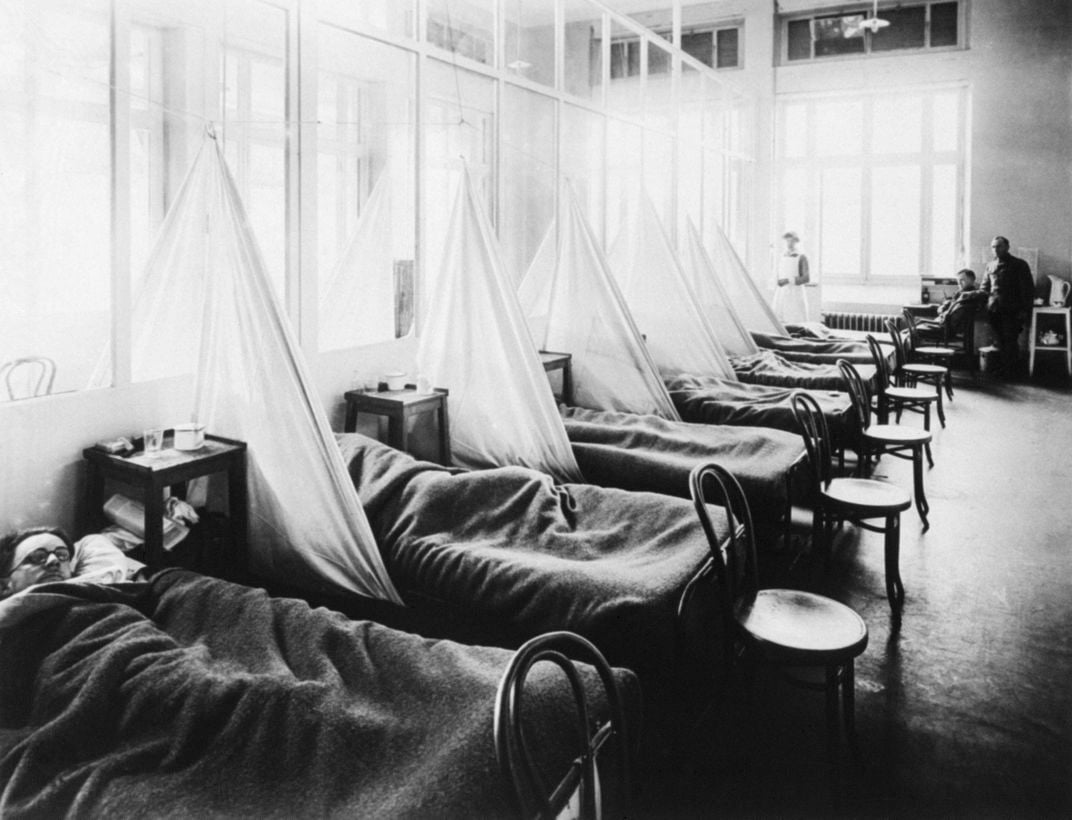

Fort Devens, a military camp about 40 miles from Boston, was among the sites hardest hit by the 1918 influenza epidemic. On September 1, some 45,000 soldiers waiting to be deployed to France were stationed at the fort; by September 23, according to the New England Historical Society, 10,500 cases of the flu had broken out among this group of military men.

Physician N. Roy Grist described the devastation to his friend Burt in a graphic September 29 letter sent from Devens’ “Surgical Ward No. 16.”

These men start with what appears to be an attack of la grippe or influenza, and when brought to the hospital they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies sort of gets on your nerves.

On average, wrote the doctor, around 100 patients died each day.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/15/5515e1a8-ae57-406f-a32e-d43c7b3ec45d/bh__nurses.jpg)

Grist’s letter is “a remarkably distinct and accurate description of what it was like to be in the midst of this,” says Bristow. “And then it goes on to talk about how difficult it is to be a doctor, … this sense of not being able to do as much as one might like and how exhausting it all is.”

Toward the end of the letter, Grist notes how much he wishes Burt, a fellow physician, was stationed at Fort Devens with him.

It’s more comfortable when one has a friend about. ... I want to find some fellow who will not ‘talk shop’ but there ain’t none, no how. We eat it, sleep it, and dream it, to say nothing of breathing it 16 hours a day. I would be very grateful indeed if you would drop me a line or two once in a while, and I promise you that if you ever get into a fix like this, I will do the same for you.

Clara Wrasse

From the National WWI Museum and Memorial

In September 1918, 18-year-old Clara Wrasse wrote a letter to her future husband, Reid Fields, an American soldier stationed in France. Though her home city of Chicago was in the midst of battling an epidemic, influenza was, at best, a secondary concern for the teenager, who reported:

About four hundred [people] died of it at the Great Lakes … quite a number of people in Chi are suffering with it too. Mother thought that I had it when I wasn’t feeling good, but I am feeling fine now.

Quickly moving on from this mention of disease, Wrasse went on to regale her beau with stories of life in Chicago, which she deemed “to be the same old city, altho there are lots of queer things happening.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/78/5978c9c1-81f8-4b29-bdbd-1750d71088cd/080_20151624_clara_wrasse_to_reid_fields_september_25_1918_page_01.jpg)

Signing off with the lines “hoping you feel as happy as you did when we played Bunco together,” Wrasse added one last postscript: “Any time you haven’t got anything to do, drop me a few lines, as I watch for a letter from you like a cat watches a mouse.”

Vogt of the National World War I Museum cites Wrasse’s letters as some of her favorites in the Kansas City museum’s collections.

“It's so clear how similar across the ages teenagers are and what interests them,” she says, “and that … they’re kind of wooing each other in these letters in a way that a teenager would.”

Leo Baekeland

From the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/9c/189c3d73-61ca-43e3-9b13-33696aedad2f/800px-leo_hendrik_baekeland_1916.jpg)

Inventor Leo Baekeland, creator of the world’s first commercialized plastic, “documented his life prolifically” in diaries, laboratory notebooks, photographs and correspondence, according to the museum’s archives center, which houses 49 boxes of the inventor’s papers.

Baekeland’s fall 1918 journal offers succinct summaries of how the epidemic affected his loved ones. On October 24, he reported that a friend named Albert was sick with influenza; by November 3, Albert and his children were “better and out of bed, but now [his] wife is sick with pneumonia.” On November 10, the inventor simply stated, “Albert’s wife is dead”—a to-the-point message he echoed one week later, when he wrote that his maid, Katie, was “buried this morning.”

Perhaps the most expressive sentiment found among Baekeland’s entries: “From five who had influenza, two deaths!”

Dorman B.E. Kent

From the Vermont Historical Society

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/fb/a0fb306a-e545-40b6-b1f7-3d56659b9205/screen_shot_2020-04-07_at_101133_am.png)

From the age of 11 to his death at 75 in 1951, Dorman B.E. Kent recorded his life in diaries and letters. These papers—now held by the Vermont Historical Society, where Kent served as a librarian for 11 years—document everything from his childhood chores to his views on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and his sons’ career progress.

Of particular interest is Kent’s fall 1918 diary, which contains vivid descriptions of his own bout with influenza. On September 24, he wrote (as mentioned above):

Awoke at 7:00 [a.m.] sick, sick, sick. Didn’t get up or try to. Had a high fever an awful headache every minute all day and was sick to my stomach also. Tried to get Dr. Watson in the morning but he couldn’t come. Told us instead what to do. Greased cloths with inflamacene all day and put around throat and chest and held a bottle of hot water at throat most of the time. Took a seidlitz powder about 10.00 and threw it up soon so then took two tablespoons of castor oil. Then the movements began and I spent a good part of the time at the seat … There is a tremendous lot of influenza in town.

Kent recovered within a few days, but by the time he was able to resume normal activities, his two sons had come down with the flu. Luckily, all three survived the illness.

In early October, Kent participated in a door-to-door census count of the disease’s toll. Surveying two wards in Montpelier on October 2, he and his fellow volunteers recorded 1,237 sick in bed, 1,876 “either ill or recovered,” and 8 dead in one night. The following day, Kent reported that “25 have died in Barre today & the conditions are getting worse all the while. … Terrible times.”

Donald McKinney Wallace

From the Wright State University Special Collections and Archives

Partially transcribed by Lisa Powell of Dayton Daily News

Donald McKinney Wallace, a farmer from New Carlisle, Ohio, was serving in the U.S. Army when the 1918 pandemic broke out. The soldier’s wartime diary detailed conditions in his unit’s sick bay—and the Army’s response to the crisis. On September 30, Wallace wrote:

Layed in our sick ward all day but am no better, had a fever all day. This evening the Doctor had some beef broth brought down to us which was the first I had eaten since last Fri. Our ward was fenced off from rest of the barrack by hanging blankets over a wire which they stretched clear across the ceiling.

On October 4, the still-ailing farmer added, “Not a bit well yet but anything is better than going over to the hospital. 2 men over there have Spanish Influenza bad and are not expected to live. We washed all windows and floors with creoline solution tonight.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/fe/9bfe8087-676a-46cd-aca6-34b1c5d11d49/screen_shot_2020-04-07_at_105943_am.png)

Wallace survived his illness (and the war), dying in 1975 at age 78.

Though Wallace’s writings don’t reference the situation in his hometown, Bristow notes that many soldiers expressed concern for their families in correspondence sent from the front.

“You get these letters from soldiers who are so worried about their families at home,” she says, “and it’s not what anyone had expected. Their job was to go off soldiering, and the family would worry about them. And now, suddenly, the tables are turned, and it’s really unsettling.”

Helen Viola Jackson Kent

From Utah State University’s Digital History Collections

When Helen Viola Jackson Kent’s children donated her journals to Utah State University, they offered an apt description of the purpose these papers served. Like many diary writers, Kent used her journal to “reflect her daily life, her comings and goings, her thoughts, her wishes, her joys, and her disappointments.”

On November 1, 1918, the lifelong Utah resident wrote that she “[h]ad a bad head ache all day and did not accomplish much. Felt very uneasy as I found out I was exposed to the ‘flu’ Wed. at the store.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/ba/0ebab8ce-b113-470d-9839-fcfb04d67036/gettyimages-3423478.jpg)

Kent escaped the flu, but her husband, Melvin—called “Mell” in her diary—was not so lucky. Still, Melvin managed to make a full recovery, and on November 18, his wife reported:

Mell much better and dressed today. Almost worn out with worry and loss of sleep. So much sickness and death this week, but one great ray of light and hope on the outcome of the war as peace came this past [11th].

Interestingly, Kent also noted that the celebrations held to mark the end of World War I had sparked an inadvertent uptick in illness.

“On account of the rejoicing and celebrating,” she wrote, “this disease of influenza increased everywhere.”

:focal(294x145:295x146)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/3a/c13afad2-7bfd-40fc-869d-b9240adf9a8e/influenza_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/33/5933f953-d73a-4940-aca4-f6592a11ccc0/influenza_main_longform.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)