What Schools Teach About Women’s History Leaves a Lot to Be Desired

A recent study broke down each state’s educational standards to see whose ‘herstory’ was missing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/15/0c15d6d4-9cf9-4938-bd92-8cf8cee45108/istock-533610081.jpg)

In the introduction to her 1970 anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful, author and activist Robin Morgan wrote that the women’s liberation movement was “creating history, or rather, herstory,” coining the popular term that second-wave feminists used to highlight the way in which women were consistently overlooked in historical narratives.

Though women have made strides in countless arenas, breaking glass ceilings everywhere, the canon of American history, at least as it is taught in public schools, still has much room for reexamination and advancement.

About two years ago, authors with the virtual National Women’s History Museum analyzed the K-12 educational standards in social studies for each of the 50 states and Washington, D.C. They published their findings in Where Are the Women?, a 2017 report on the status of women in the standards that dictate who and what is taught in classrooms. Their report found just how few women are required reading in America’s schools.

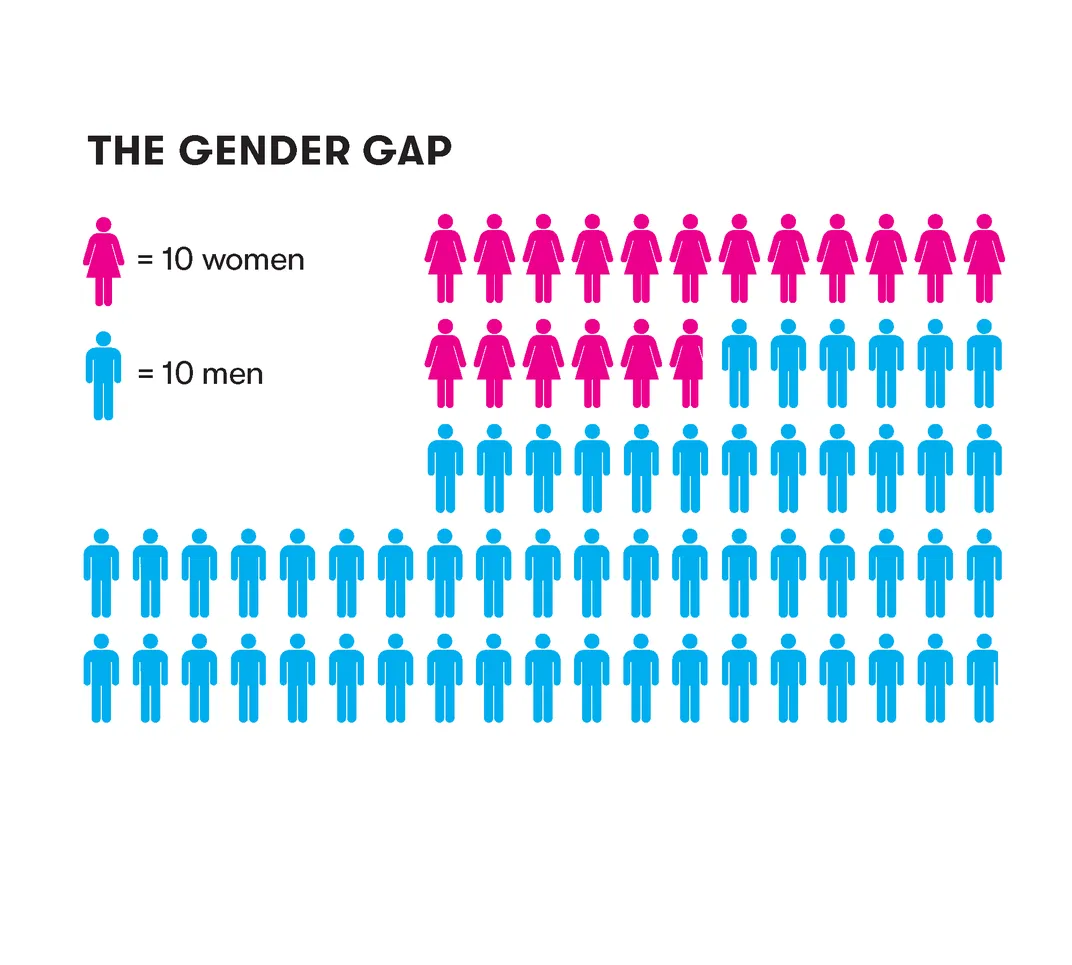

According to Smithsonian’s calculations, 737 specific historical figures—559 men and 178 women, or approximately 1 woman for every 3 men—are mentioned in the standards in place as of 2017. Aside from the individuals explicitly named, many references to women feel like an afterthought, grouped in with other minorities as they are in the Florida standard for high school social studies, which prompts educators to teach their classes about significant inventors of the Industrial Revolution, “including an African American or a woman.”

“The standards don't reflect the breadth and depth of all women's contributions to history,” says Lori Ann Terjesen, the director of education at the museum, which has no physical location but curates online exhibitions and provides resources for educators. Terjesen cautions that data for the study was compiled in 2017, and some states, like Texas, have since updated their social studies curricula.

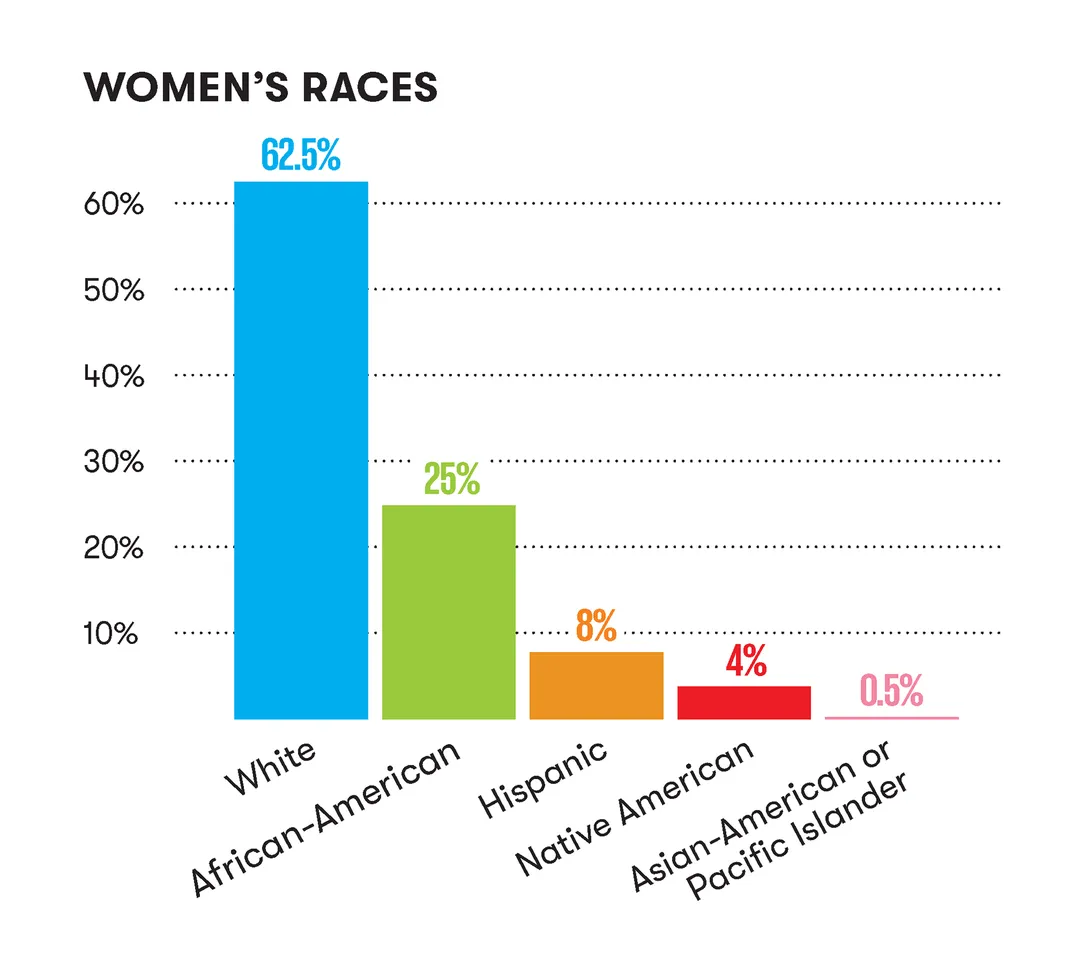

The standards also fail to reflect the racial demographic of the children they are intended to educate. In 2014, 54 percent of U.S. adolescents were white, and this is estimated to drop to 40 percent by 2050 as the U.S. becomes increasingly multiracial. The demographic of women mentioned in the standards, however, is still 62 percent white, and only one woman of Asian or Pacific Islander descent, Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii, is named at all. African-American women comprise 25 percent of those named, including Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, who are three of the top five most-often cited figures named in the standards.

Among the other most-often cited women are suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, First Lady Abigail Adams, Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe, pioneering social worker Jane Addams, abolitionist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Eleanor Roosevelt and Sacagawea. Perhaps the most surprising of the ten most mentioned is Norma McCorvey, better known as the pseudonymous plaintiff Jane Roe in the 1973 Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade.

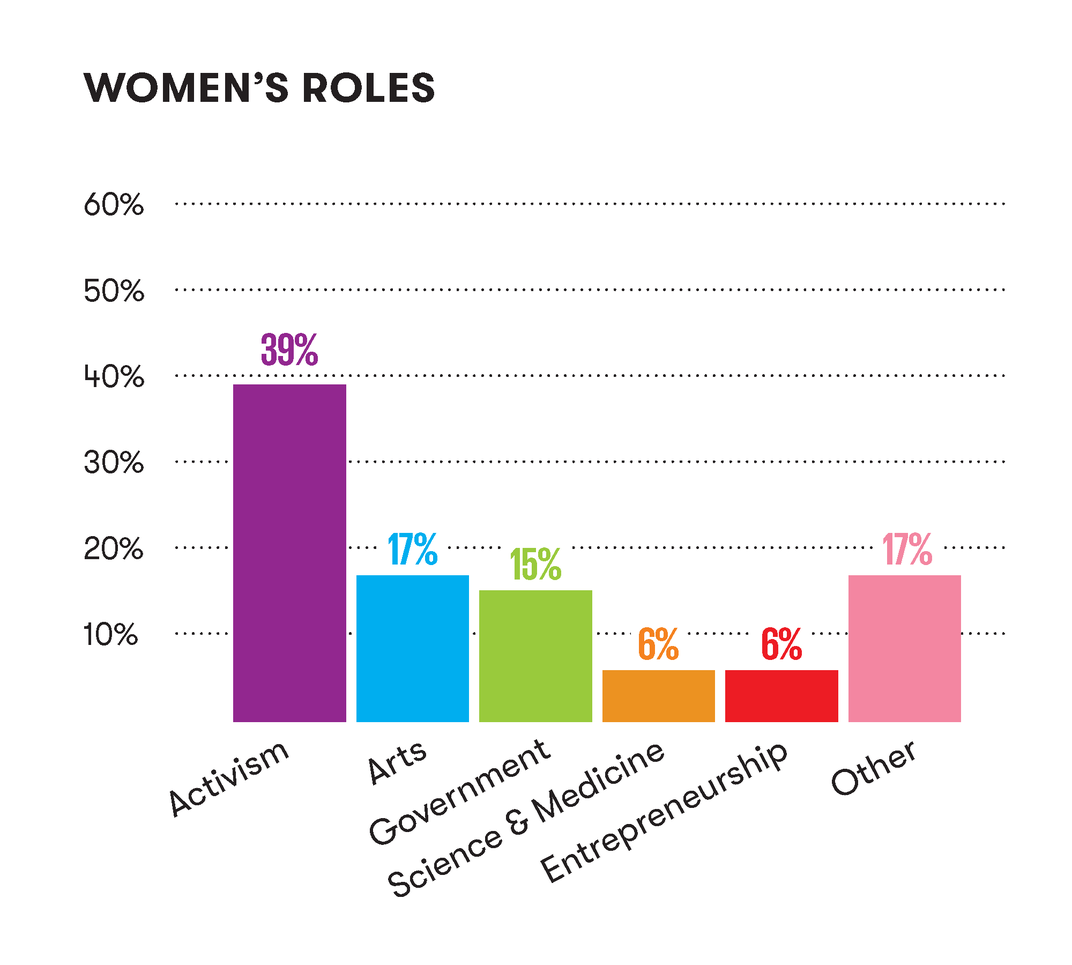

The report also analyzed the roles of the women most frequently mentioned, showing a breadth of professional roles from activism to the arts to government and exploration. But a closer examination of the subject matters in which women in general are discussed reveals a problematic pattern. Fifty-three percent of mentions of women’s history fall within the context of domestic roles, with women’s rights and suffrage making up only 20 percent of the mentions. According to the museum, this emphasis on women’s domestic roles, and exclusion from other important chapters in American history, hits to the core of what they see as the problem. Students who learn by the standards handed down by state education boards fail to see the broader impacts women made on U.S. history.

In the United States, education is viewed as primarily a state responsibility. Though some initiatives, like the 2010 Common Core State Standards, provide consistent education standards for K-through-12 students across the country. Common Core doesn’t cover all subject matters, including history, leaving each state to provide its own guidelines for teaching students about our past.

“All history projects require choices,” write the study’s authors. “Women often don’t make the cut.”

Of the women who do make the cut, many of them are unique to their state. Out of the 178 women mentioned in the social studies standards, 98 of them appear just once. Below is a sampling of some of these women:

Josephine Pearson • Tennessee

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/1c/cc1c0c15-2514-48c9-a2b2-50c48da833be/mar19_pro_portraits5.jpg)

A leading voice against women’s suffrage a century ago, she said the responsibility of voting would be a burden for women and a threat to the Southern way of life.

Lizzie Johnson • Texas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/c9/aec98878-c816-4f5f-bb6e-9f4257b157a1/mar19_pro_portraits3.jpg)

The “Cattle Queen of Texas” found success among the cowboys in the 1870s. She owned a ranch, registered her own brand and drove her longhorns along the Chisholm Trail.

Biddy Mason • California

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/37/9137dc09-4a88-479a-ba84-a1da439dc2a9/mar19_pro_potraits_biddymason.jpg)

After suing for her freedom from slavery at the age 38, Mason worked as a nurse, invested in land in the growing city of Los Angeles and became a millionaire philanthropist.

Marie Webster • Indiana

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/51/d4512360-fc9e-4cc7-82de-b8cdb581af61/mar19_pro_portraits1.jpg)

The turn-of-the-century Martha Stewart, Webster turned quilting into a thriving business. Her books and Arts and Crafts-inspired quilt patterns made her a household name.

Mary Lease • Kansas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/79/1f79cbd9-2d69-4c14-a0da-4c3eccb8ea79/mar19_pro_portraits4.jpg)

In the 1890s, long before she had the right to vote, Lease was a nationally known political orator and a prominent, if divisive, leader in the Kansas People’s Party.

Luisa Capetillo • Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/a6/6ba6bd47-8764-49b9-b124-0a2efcbb6e7d/mar19_pro_portraits8.jpg)

A Puerto Rican labor leader and feminist writer of the early 20th century, Capetillo was also known for being arrested in Havana. Her crime: wearing pants in public.

Mary Fields • Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/14/be14dd95-f7c4-4199-9990-90709c488856/mar19_pro_portraits7.jpg)

“Stagecoach Mary” was a Wild West legend, a formerly enslaved woman who carried the U.S. mail—and her rifle—through the rough-and-tumble Montana mountains in the 1890s.

Emily Roebling • New York

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/72/c472d6b2-f861-4b98-b502-f17510f39a11/mar19_pro_portraits6.jpg)

Roebling was instrumental in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in the 1870s, stepping in as surrogate chief engineer after her husband fell ill. She later earned a law degree.

Ann Story • Vermont

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/a2/8aa240d5-3705-463b-ae46-4e7d76350f5e/mar19_pro_portraits2.jpg)

When many settlers fled Vermont at the start of the Revolutionary War, Story and her children stayed. She provided the state militia with shelter and supplies and spied on the British.

The museum hopes that Where are the Women? will encourage teachers, scholars, students and parents to rethink how the historical experiences of women are presented in the classroom. The report shows that we could all stand to learn a little more about herstory.

Editor's note, March 11, 2019: An earlier version of this story featured a photograph of Biddy Mason’s daughter, Ellen Huddleston, rather than Biddy Mason herself.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnnaWhite.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnnaWhite.jpg)