Unraveling the Many Mysteries of Tituba, the Star Witness of the Salem Witch Trials

No one really knows the true motives of the character central to one of America’s greatest secrets

:focal(608x527:609x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/40/c040aaa1-cb42-4708-8d14-b08a56caaf07/nov2015_e02_tituba.jpg)

Few corners of American history have been as exhaustively or insistently explored as the nine months during which the Massachusetts Bay Colony grappled with our deadliest witchcraft epidemic. Early in 1692, several young girls began to writhe and roar. They contorted violently; they complained of bites and pinches. They alternately interrupted sermons and fell mute, “their throats choked, their limbs wracked,” an observer noted. After some hesitation, after much discussion, they were declared to be bewitched.

Their symptoms spread, initially within the community, ultimately well beyond its borders. In their distress the girls cried out against those they believed enchanted them; they could see their tormentors perfectly. Others followed suit, because they suffered the effects of witchcraft, or because they had observed it, often decades in the past. By early spring it was established not only that witches flew freely about Massachusetts, but that a diabolical conspiracy was afoot. It threatened to topple the church and subvert the country.

By the fall, somewhere between 144 and 185 witches and wizards had been named. Nineteen men and women had hanged. America’s tiny reign of terror burned itself out by late September, though it would endure allegorically for centuries. We dust it off whenever we overreach ideologically or prosecute overhastily, when prejudice rears its head or decency slips down the drain, when absolutism threatens to envelop us. As often as we have revisited Salem—on the page, on the stage and on the screen—we have failed to unpack a crucial mystery at the center of the crisis. How did the epidemic gather such speed, and how did it come to involve a satanic plot, a Massachusetts first? The answers to both questions lie in part with the unlikeliest of suspects, the Indian slave at the heart of the Salem mystery. Enigmatic to begin, she has grown more elusive over the years.

We know her only as Tituba. She belonged to Samuel Parris, the minister in whose household the witchcraft erupted; his daughter and niece were the first to convulse. Although she was officially charged with having practiced witchcraft on four Salem girls between January and March, we do not know precisely why Tituba was accused. Especially close to 9-year-old Betty Parris, she had worked and prayed alongside the family for years, for at least a decade in Boston and Salem. She took her meals with the girls, beside whom she likely slept at night. Tituba may have sailed from Barbados in 1680 with Parris, then still a bachelor and not yet a minister. Though likely a South American Indian, her origins are unclear.

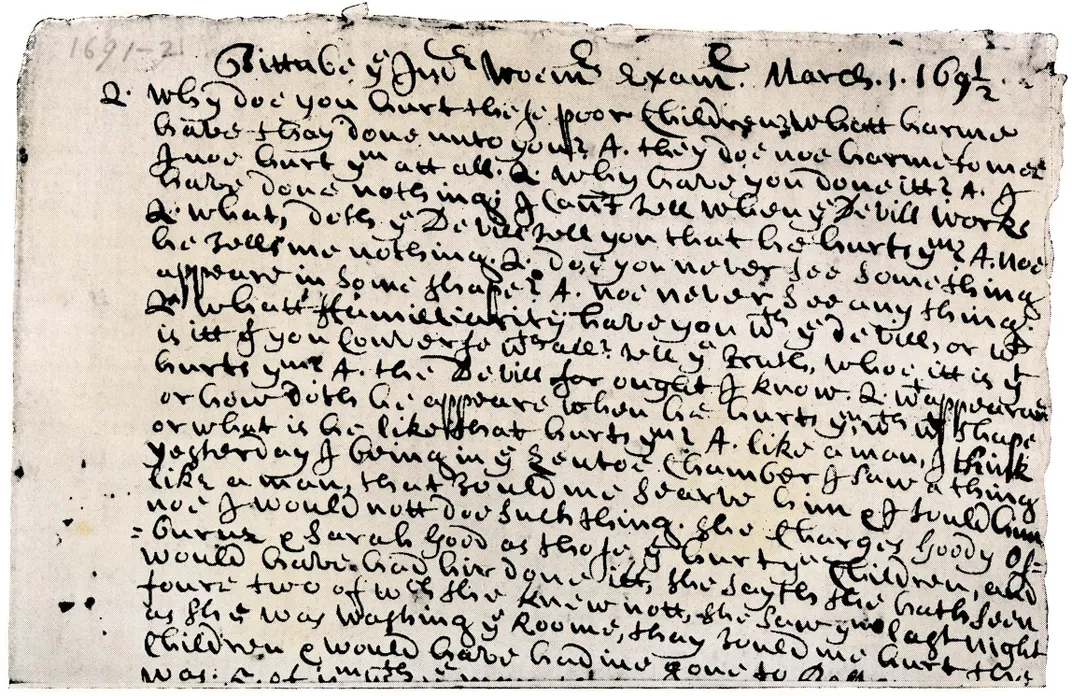

She could not have expected to be accused. New England witches were traditionally marginals: outliers and deviants, cantankerous scolds and choleric foot-stompers. They were not people of color. Tituba does not appear to have been complicit in an early attempt to identify the village witches, a superstitious experiment performed in the parsonage while the adult Parrises were away. It infuriated the minister. She had never before appeared in court. At least some villagers assumed her to be the wife of a second Parris slave, an Indian named John. English was clearly not her first language. (To the question, “Why do you hurt these children?” Tituba responded, “I no hurt them at all.”)

She was presumably not a large woman; she would expect the Salem justices to believe that two other suspects had strong-armed her into a high-speed excursion through the air, while all held close to one another on a pole. She was the first in Salem to mention a flight.

Along with those women, Tituba came before the authorities in Salem Village on March 1, 1692, to answer to witchcraft charges. The first two suspects denied all knowledge of sorcery. When Tituba met her interrogators that Tuesday morning, she stood before a packed, nervous meetinghouse. It was the one in which she had prayed for the previous three years. She had already been deposed in prison. The local authorities seemed to understand before she opened her mouth that she had a confession to offer. No other suspect would claim such attention; multiple reporters sat poised to take down Tituba’s words. And someone—presumably hard-edged, 51-year-old John Hathorne, the Salem town justice who handled the bulk of the early depositions—made the decision to interrogate her last.

She began with a denial, one with which the court reporters barely bothered. Hathorne had asked the first suspects whom they employed to hurt the girls. The question went to Tituba with a different spin. “The devil came to me,” she revealed, “and bid me serve him.” As a slave, she could not so easily afford to sound a defiant note. And it was indisputably easier for her to admit she served a powerful man than it might have been for her fellow prisoners, both white women. In custody, one scoffed that the word of a smooth-talking slave should carry no weight. She was right about the smooth-talking part, miserably wrong about the rest.

Who was it, demanded Hathorne, who tortured the poor girls? “The devil, for all I know,” Tituba rejoined before she began describing him, to a hushed room. She introduced a full, malevolent cast, their animal accomplices and various superpowers. A sort of satanic Scheherazade, she was masterful and gloriously persuasive. Only the day before, a tall, white-haired man in a dark serge coat had appeared. He traveled from Boston with his accomplices. He ordered Tituba to hurt the children. He would kill her if she did not. Had the man appeared to her in any other guise? asked Hathorne. Here Tituba made clear that she must have been the life of the corn-pounding, pea-shelling Parris kitchen. She submitted a vivid, lurid and harebrained report. More than anyone else, she propelled America’s infamous witch hunt forward, supplying its imagery and determining its shape.

She had seen a hog, a great black dog, a red cat, a black cat, a yellow bird and a hairy creature that walked on two legs. Another animal had turned up too. She did not know what it was called and found it difficult to describe, but it had “wings and two legs and a head like a woman.” A canary accompanied her visitor. If she served the black-coated man, she could have the bird. She implicated her two fellow suspects: One had appeared only the night before, with her cat, while the Parris family was at prayer. She had attempted to bargain with Tituba, stopping her ears so that Tituba could not hear the Scripture. She remained deaf for some time afterward. The creature she claimed to have so much trouble describing (and which she described vividly) was, she explained, Hathorne’s other suspect, in disguise.

She proved a brilliant raconteur, the more compelling for her simple declarative statements. The accent may have helped. She was as utterly clear-minded and cogent as one could be in describing translucent cats. And she was expansive: Hers is among the longest of all Salem testimonies. Having fielded no fewer than 39 queries that Tuesday, Tituba proved equally obliging over the next days. She admitted that she had pinched victims in several households. She delivered on every one of Hathorne’s leading questions. If he mentioned a book, she could describe it. If he inquired after the devil’s disguises, she could provide them.

While she was hauntingly specific, she was also gloriously vague. Indeed she had glimpsed the diabolical book. But she could not say if it was large or small. The devil might have had white hair; perhaps he had not. While there were many marks in the book, she could not decipher names other than those of the two women already under arrest. Other confessors would not be so careful. Did she see the book? “No, he no let me see, but he tell me I should see them the next time,” she assured Hathorne. Could she at least say where the nine lived? “Yes, some in Boston and some here in this town, but he would not tell me who they were,” she replied. She had signed her pact with the devil in blood, but was unclear as to how that was accomplished. God barely figured in her testimony.

At a certain point she found that she could simply not continue. “I am blind now. I cannot see!” she wailed. The devil had incapacitated her, furious that Tituba liberally dispensed his secrets. There was every reason why the girls—who had howled and writhed through the earlier hearings—held stock still for that of an Indian slave. There was equal reason why Tituba afterward caused grown men to freeze in their tracks. Hours after her testimony, they trembled at “strange and unusual beasts,” diaphanous creatures that mutated before their eyes and melted into the night. And she would herself undergo a number of strange and unusual transformations, with the assistance of some of America’s foremost historians and men of letters.

Confessions to witchcraft were rare. Convincing, satisfying and the most kaleidoscopically colorful of the century, Tituba’s changed everything. It assured the authorities they were on the right track. Doubling the number of suspects, it stressed the urgency of the investigation. It introduced a dangerous recruiter into the proceedings. It encouraged the authorities to arrest additional suspects. A satanic conspiracy was afoot! Tituba had seen something of which every villager had heard and in which all believed: an actual pact with the devil. She had conversed with Satan but had also resisted some of his entreaties; she wished she had held him off entirely. She was deferential and cooperative. All would have turned out very differently had she been less accommodating.

Portions of her March account would soon fall away: The tall, white-haired man from Boston would be replaced by a short, dark-haired man from Maine. (If she had a culprit in mind, we will never know who it was.) Her nine conspirators soon became 23 or 24, then 40, later 100, ultimately an eye-popping 500. According to one source, Tituba would retract every word of her sensational confession, into which she claimed her master had bullied her. By that time, arrests had spread across eastern Massachusetts on the strength of her March story, however. One pious woman would not concede witchcraft was at work: How could she say as much, she was asked, given Tituba’s confession? The woman hanged, denying—as did every 1692 victim—any part of sorcery to the end. All agreed on the primacy of Tituba’s role. “And thus,” wrote a minister of her hypnotic account, “was this matter driven on.” Her revelations went viral; an oral culture in many ways resembles an Internet one. Once she had testified, diabolical books and witches’ meetings, flights and familiars were everywhere. Others among the accused adopted her imagery, some slavishly. It is easier to borrow than invent a good story; one confessor changed her account to bring it closer in line with Tituba’s.

There would be less consensus afterward, particularly when it came to Tituba’s identity. Described as Indian no fewer than 15 times in the court papers, she went on to shift-shape herself. As scholars have noted, falling prey to a multi-century game of telephone, Tituba evolved over two centuries from Indian to half-Indian to half-black to black, with assists from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (who seemed to have plucked her from Macbeth), historian George Bancroft and William Carlos Williams. By the time Arthur Miller wrote The Crucible, in 1952, Tituba was a “Negro slave.” She engaged in a different brand of dark arts: To go with her new heritage, Miller supplied a live frog, a kettle and chicken blood. He has Tituba sing her West Indian songs over a fire, in the forest, as naked girls dance around. Sounding like a distant cousin of Mammy in Gone With the Wind, she says things like: “Mister Reverend, I do believe somebody else be witchin’ these children.” She is last seen in a moonlit prison sounding half-crazed, begging the devil to carry her home to Barbados. After The Crucible, she would be known for her voodoo, of which there is not a shred of evidence, rather than for her psychedelic confession, which endures on paper.

Why the retrofitted racial identity? Arguably bias played a role: A black woman at the center of the story made more sense, in the same way that—as Tituba saw it—a man in black belonged at the center of a diabolical conspiracy. Her history was written by men, working when African voodoo was more electrifying than outmoded English witchcraft. All wrote after the Civil War, when a slave was understood to be black. Miller believed Tituba had actively engaged in devil worship; he read her confession—and the 20th-century sources—at face value. By replacing the Salem justices as the villain of the piece, Tituba exonerated others, the Massachusetts elite most of all. In her testimony and her afterlife, preconceptions neatly shaped the tale: Tituba delivered on Hathorne’s leads as she knew her Scripture well. Her details tallied unerringly with the reports of the bewitched. Moreover, her account never wavered. “And it was thought that if she had feigned her confession, she could not have remembered her answers so exactly,” an observer explained later. A liar, it was understood, needed a better memory.

It seems the opposite is true: The liar sidesteps all inconsistencies. The truth-teller rarely tells his story the same way twice. With the right technique, you can pry answers out of anyone, though what you extract won’t necessarily be factual answers. Before an authority figure, a suggestible witness will reliably deliver planted or preposterous memories. In the longest criminal trial in American history—the California child abuse cases of the 1980s—children swore that daycare workers slaughtered elephants. Tituba’s details too grew more and more lush with each retelling, as forced confessions will. Whether she was coerced or whether she willingly collaborated, she gave her interrogators what she knew they wanted. One gets the sense of a servant taking her cues, dutifully assuming a pre-scripted role, telling her master precisely what he wants to hear—as she has from the time of Shakespeare or Molière.

If the spectral cats and diabolical compacts sound quaint, the trumped-up hysteria remains eminently modern. We are no less given to adrenalized overreactions, all the more easily transmitted with the click of a mouse. A 17th-century New Englander had reason for anxiety on many counts; he battled marauding Indians, encroaching neighbors, a deep spiritual insecurity. He felt physically, politically and morally besieged. And once an idea—or an identity—seeps into the groundwater it is difficult to rinse out. The memory is indelible, as would be the moral stain. We too deal in runaway accusations and point fingers in the wrong direction, as we have done after the Boston Marathon bombing or the 2012 University of Virginia rape case. We continue to favor the outlandish explanation over the simple one; we are more readily deceived by a great deception—by a hairy creature with wings and a female face—than by a modest one. When computers go down, it seems far more likely that they were hacked by a group of conspirators than that they simultaneously malfunctioned. A jet vanishes: It is more plausible that it was secreted away by a Middle Eastern country than that it might be sitting, in fragments, on the ocean floor. We like to lose ourselves in a cause, to ground our private hurts in public outrages. We do not like for others to refute our beliefs any more than we like for them to deny our hallucinations.

Having introduced flights and familiars into the proceedings, having delivered a tale that could not be unthought, Tituba was neither again questioned nor so much as named. She finally went on trial for having covenanted with the devil on May 9, 1693, after 15 harrowing months in prison. The jury declined to indict her. The first to confess to signing a diabolical pact, she would be the last suspect released. She appears to have left Massachusetts with whoever paid her jail fees. It is unlikely she ever saw the Parris family again. After 1692 no one again attended to her every word. She disappears from the record though did escape with her life, unlike the women she named as her confederates that March Tuesday. Tituba suffered only the indignity of a warped afterlife, for reasons she might have appreciated: It made for a better story.

The Witches: Suspicion, Betrayal, and Hysteria in 1692 Salem

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Cleopatra, the #1 national bestseller, unpacks the mystery of the Salem Witch Trials.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.