The First “Teflon” Hero

What July 4th, 1754 reveals about George Washington’s survival skills

The Other July 4th, or "Washington's Confession"

Adapted from Chapter 3 of American's Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a Nation, by Kenneth C. Davis.

Church bells pealed and bonfires blazed as a celebratory mood swept over Philadelphia following adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Days later in New York, the still-green army that had forced the British from Boston a few months earlier would gather for a reading of the historic document by order of General Washington.

But for Washington himself, the triumphal spirit of that epochal July 4th must have been tempered by bitter memories. On that date, more than 20 years earlier in 1754, the strapping, twenty-two-year-old militia commander had surrendered to an enemy for the first and only time in his career. Then he signed a murder confession.

The incident began in late May 1754, with England and France in a brief respite from years of relentless war. Relying upon knowledge garnered from reading military manuals, the wet-behind-the-ears Washington was in command of a crew of militiamen dispatched to build an outpost in western Pennsylvania's contested wilderness.

Encountering a detachment of French soldiers, Washington followed the advice of an ally he barely trusted—an Indian chief known to the English as the Half King. Tossing caution to the wind, the untested Washington defied orders and ambushed the French. When the smoke cleared, one Virginian and several Frenchmen lay dead or wounded; the rest were taken prisoner. "I heard bullets whistle," Washington later told his brother, famously adding that the sound was "charming."

What happened next was anything but charming. A wounded French officer frantically waved some papers at Washington. He was, in fact, a diplomat, carrying letters to the British. But before Washington could make sense of this, the Half King buried his tomahawk in the Frenchman's brain. The Indians fell on the other captives, leaving few alive.

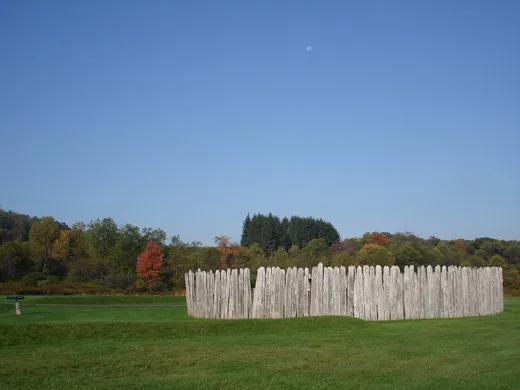

Following this massacre, a French army set off in hot pursuit of Washington. Outnumbered, Washington's men cobbled together a small wooden shed, surrounded by sharpened stakes, in a meadow about 60 miles south of what is now Pittsburgh. It was called "Fort Necessity" but "Desperation" would have been more fitting. The Half King's warriors took one look and beat a hasty retreat.

On a rainy July 3rd, the French surrounded Fort Necessity and poured gunfire down on Washington's hapless troops. Their powder wet, their trenches filling with mud and gore, some of the Virginians ransacked the rum stores. By the morning of the 4th, Washington had no choice. Fortunate he wasn't shot on the spot, he accepted terms. Among them was signing what amounted to a murder confession. His admission sparked the Seven Years' War, history's first true "world war." (The North American phase was the French and Indian War.)

Insubordinate, incompetent, an admitted murderer who had surrendered in abject defeat—Washington should have been done in by any of these blows to his reputation. But instead, he flourished. The first "Teflon" hero in American history—nothing stuck to the young George Washington.

Clearly, he possessed uncanny survival skills. He had proven that in 1753, during a dangerous trek through the Ohio River Valley wilderness when he was shot at by an Indian and later plunged into an icy river. By all rights, Washington should have died of exposure. But he lived to tell the tale and made a name for himself.

A second, more political factor bolstered Washington after his inglorious July 4th debacle. Instead of being upbraided and sacked, he was praised by the Virginia legislature for his courage in the face of the "depraved" French and their "savage" Indian allies. Washington benefited from some 18th-century "spin" as the British turned the Fort Necessity fiasco into a propaganda coup to rally opinion against the enemy.

Just as intriguing as this public reversal of Washington's failures is how they escaped inclusion in your schoolbooks. Maybe it is this simple: his "youthful indiscretions" never fit the tidy "I-cannot-tell-a-lie" image of young Washington that many Americans still cherish. As historian Andrew Burstein once wrote, "We gauge our prospects as a people by locating a past from which we can draw hope and pride." Many Americans still cling to the mythic version of history with heroes as perfectly polished as the marble monuments in the nation's capitol.

Yet the tale of "Washington's Confession" is not simply revisionism meant to tarnish an icon. Washington emerged as the "indispensable man" who saw combat at its worst, learned well the politics of war, and was surely shaped by these disastrous misadventures. The measured, and generally indomitable, spirit he later demonstrated, as commander facing daunting odds and then as President, was molded by what has been called his "forge of experience."

Perhaps, then, Washington's confession is just one piece of America's "hidden history," a reminder that winners tell the tales. And Washington was a winner. Even though as he surely knew—it is often the defeats and disasters that can teach us the most.

Adapted from America's Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a Nation, by Kenneth C. Davis. Copyright© 2008 by Kenneth C. Davis. By permission of Smithsonian Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.