The Strange Nature of the First Printed Illustration of a Sloth

As described by a 16th-century French missionary, the South American ‘little bear’ with the face of ‘a baby’ was introduced to Europe

:focal(661x628:662x629)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/66/7d668b6f-8f9e-4ef6-a6c5-2e8dd5845436/sloth-illo.jpg)

The slow-moving sloth is now something of an internet sensation, with long claws that wouldn’t be out of place on Freddy Krueger’s hand wielded by an endearingly fuzzy creature. Centuries ago, the sloth fascinated European travelers to South America, who weren’t quite sure what to make of this unfamiliar animal, as well as readers who were captivated by their written accounts.

This week, an example of what is believed to be the first printed illustration of a sloth will be up for auction as part of a fine books and manuscripts auction at Christie’s in New York. It appears in the 1557 Les Singularitez de la France Antarctique (Singularities of France Antarctique) by André Thevet, a French Franciscan friar who joined a 1555 expedition to the French Protestant colony of France Antarctique in today's Rio de Janeiro. His manuscript and its woodcuts, attributed to artist Jean Cousin, represent, with varying degrees of accuracy, the flora, fauna, and people of Brazil.

“[This book] is one of these really special books, because it's the way that this information was transmitted,” says Rhiannon Knol, junior specialist in books and manuscripts at Christie’s auction house. “It's hard not to think that for its first few owners, it’s the most amazing thing you can imagine. It's telling you that monsters are real, that there's a whole other world that you never knew of.”

Thevet only spent 10 weeks in Brazil, his time reportedly cut short due to illness. Although Thevet had entered the Franciscan monastery at a young age, he did not limit his studies to religion, having also read much about science. Before voyaging to Brazil, he traveled around Europe and journeyed further to Egypt, Lebanon and other parts of the Middle East, so it was a recognized cosmographer with a curiosity for the natural world and a passion for travel who accepted French vice-admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon's invitation to join an expedition to Brazil to establish a French colony.

As Manoel da Silveira Cardozo wrote in a 1944 article for The Americas, to a man "with his great interest in natural history, the opportunity afforded him to know the natives, to observe the exuberant fauna and flora, to collect objects of various sorts, must have filled him with delight." Although he had intentions for converting indigenous people, he "soon gave it up" and instead joined the French sailors in exploring the local terrain.

“This book has so many firsts because he was one of the first people to really report on and then publish with illustrations some of these New World creatures,” says Knol. It includes some of the earliest descriptions of a toucan, a tapir, a bison, and someone smoking a cigar.

Thevet started work on Les Singularitez almost immediately upon returning to France. The book became a compilation of his own ventures as well as second-hand knowledge, including descriptions of South America obtained from French sailors. His text suggests that he had some first-hand experience with sloths, as the description is much more accurate than the illustration attributed to Cousin. Thevet writes that it has "the size of a very large African monkey" and "three claws, four fingers long ... with which it climbs trees where it stays more than on the ground. Its tail is three fingers long, having very little hair.” Rather than take in some of the nuances, the illustration focuses on Thevet’s description of a "little bear" with a head "almost like that of a baby” and translates that to a long-clawed bear with an actual human face. Nevertheless, Thevet had some imaginative stretches of his own, as he also states that it was "never seen eating" and that the local people had watched "to see if it would feed, but all was in vain."

He says in the book that he was given one as a present and that he watched it for some 20 days and it did not eat or drink, suggesting that it might be like chameleons he had witnessed in Constantinople that lived on eating air. That sloths survived by eating air had previously been posited by Spanish writer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, who was one of the first to describe a sloth in his 1526 Historia general y natural. Since the three-toed sloths of the South American rainforest sleep over 15 hours a day and eat plants from trees by night, it's likely that these observers simply never observed them eating.

The sloth woodcut in Les Singularitez shows a bristly beast that has paused mid-stride to regard the reader. Balanced on four feet, each sprouting three long claws, it walks like no sloth known to Earth. As anyone knows who has watched a video of a sloth attempt to cross a road, they crawl at a glacial pace when on the ground, nothing like this prowling hairy creature.

The walking, baby-faced, air-eating sloth was far from Thevet's strangest inclusion. For instance, Thevet also wrote of the Succarath, a beast possibly formed from distorted descriptions of a possum or anteater. Shown with a devilish head and body akin to a lion, it was said to use its big bushy tail to shield its young who ride on its back when fleeing a predator.

As one of the earliest French books on the Americas, Thevet’s book was popular, particularly as it fit into the 16th-century genre of texts that introduced readers to distant places, shifting quickly between subjects and emphasizing the curiosity of these foreign lands. It was also borrowed by fellow authors looking to create their own chronicles of global curiosities, and his images spread through subsequent publications like a printed game of telephone. As scholars Danielle O. Moreira and Sérgio L. Mendes noted in the Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, Thevet’s work influenced representations of sloths by Europeans for decades after he first published them. They write that Thevet was “the first to write about a misshapen creature called Haüt or Haüthi,” derived from an indigenous word for the tree where it lived. His book illustration soon appeared in Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner’s 1560 Icones animalium quadrupedum viviparorum et oviparorum, and in French explorer Jean de Léry's 1578 Histoire d'un voyage fait en la terre de Brésil, in which “sloths were illustrated in trees and standing on the ground, among evil spirits tormenting the Native Americans.”

In Thevet’s manuscript, a smaller sloth is shown climbing a tree trunk. “But then you have this giant one next to it,” Knol said. “Being a fan of cryptids, it was hard [for me] not to immediately think of the giant ground sloth and the people who believe that they still exist.” Indeed, there is a legendary creature of the South American rainforests known as the mapinguari, reports of which stretch into the 20th century, which is theorized to be based on extinct ground sloths. For European readers, the perceived size of the sloth would have been colossal.

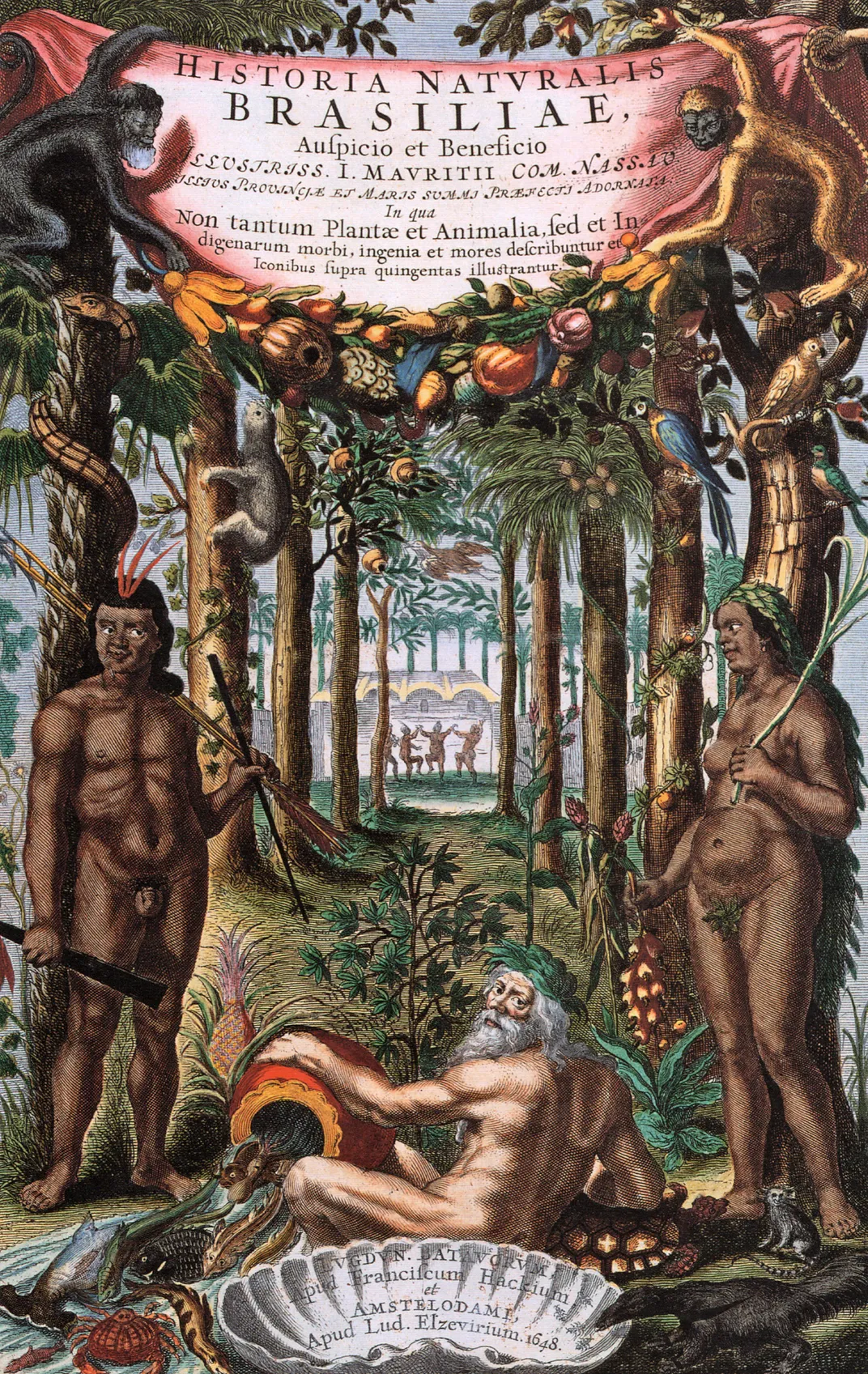

Still other 17th-century authors witnessed living sloths first hand. Art historian Larry Silver, in World of Wonders: Exotic Animals in European Imagery, 1515-1650, notes the “accurate sloth that clings to a tree trunk on the frontispiece of Georg Marcgraf and Willem Piso's Natural History of Brazil (Historia naturalis Brasiliae),” a 1648 publication based on the German naturalist Marcgraf and Dutch physician Piso's experiences in Brazil. In this title page illustration, which interprets the biblical Garden of Eden through a colonial view of Brazil, Adam and Eve are joined by palm trees, snakes, bearded monkeys, and the sloth, the whole image suggesting lush abundance, and a place supposedly untouched by civilization, ready for European control.

The French colony Thevet visited was short-lived, destroyed by the Portuguese in 1567. As more specimens, and even live animals, were transported across the Atlantic Ocean by explorers and sailors, the area’s ecology was no longer such a mystery. Nevertheless, his sloth’s hairy face recalls a time of developing European knowledge of the natural world, one being driven by the colonization of South America, where an exoticization of its lands and animals was a tool of enticement for further domination. It also reflected a growing curiosity with the natural world, and how printed books could be a window into places impossible for most readers to visit.