On the night of January 8, 1811, beginning on the Andry Plantation in Louisiana, several hundred enslaved black people overthrew their masters and began the two-day trek eastward to New Orleans, where they planned to free the region’s slaves and create a polity ruled by free blacks. It was the largest slave revolt in U.S. history—and quickly forgotten.

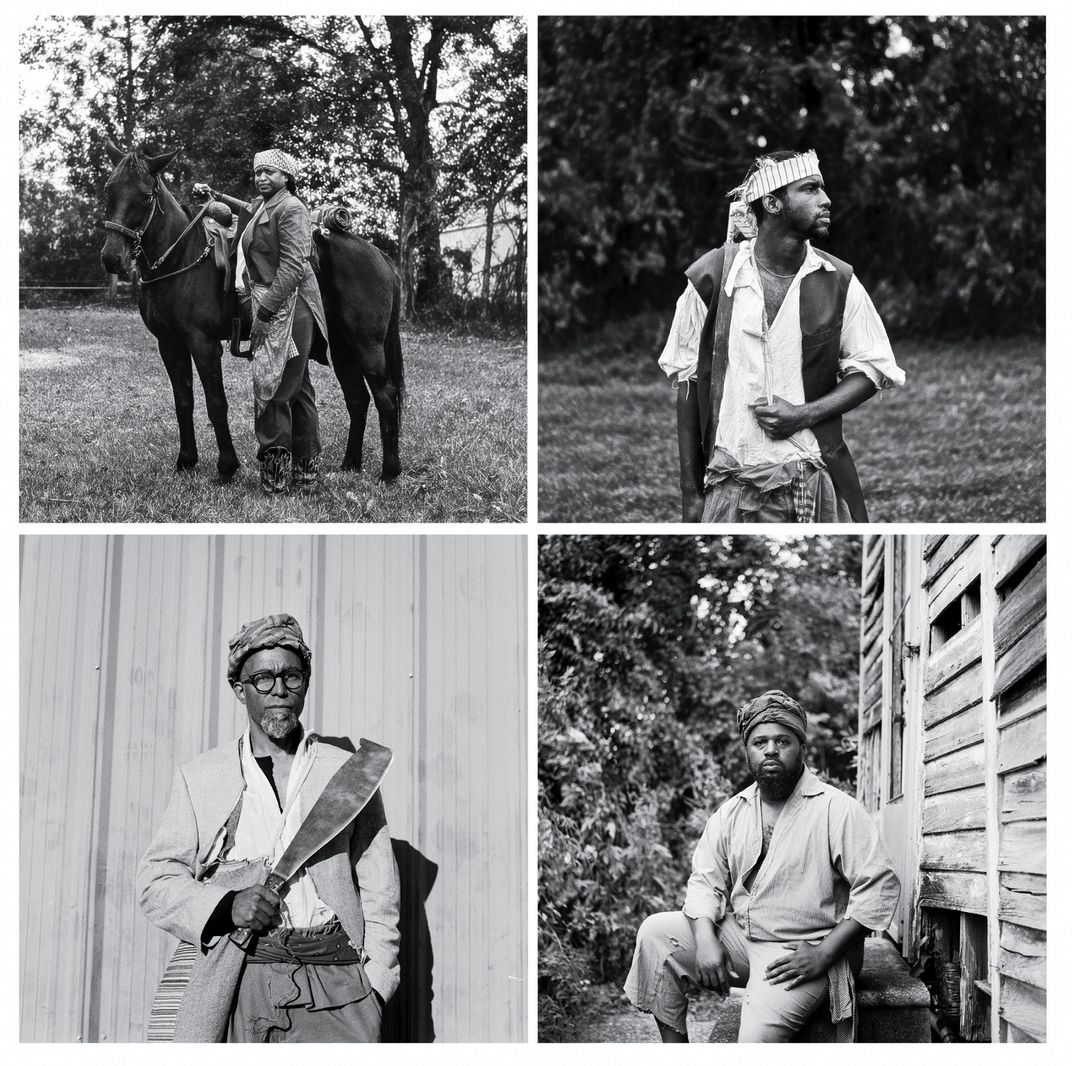

Over two days last November, more than 300 black re-enactors wearing 19th-century clothes traced the rebels’ 26-mile route from LaPlace, in St. John the Baptist Parish, through the industrial sweep of lower Louisiana—a stretch known as “cancer alley” because of high rates of the disease attributed to chemical pollutants—and into Congo Square in New Orleans. The re-enactors, some on horseback, wielded axes, pitchforks, muskets and machetes. “We’re going to end slavery!” they cried. “Onto New Orleans! Freedom or death!”

The march was the creation of the performance artist Dread Scott. “This image of a slave army is not the popular image people have of slavery,” Scott says, even though “revolts of ten or more people were actually pretty common.” He’s unsurprised that many Americans are unfamiliar with the rebellion. “There have been efforts to prevent people from knowing” about it, he says.

At the time, whites didn’t want enslaved people in other areas to be stirred by the rebellion on the German Coast, named for an influx of German settlers to Louisiana in the 18th century. As Daniel Rasmussen writes in American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt, the government and slave owners “sought to write this massive uprising out of the history books,” and were quite successful in doing so.

A Louisiana government militia crushed the original uprising on the morning of January 10. After trials on the plantations, most of the insurgents were executed, dismembered and displayed. The heads of many participants came to adorn pikes along River Road on the Mississippi.

To Scott, the sight of re-enactors in antebellum garb marching through a modern industrial landscape is not as jarring as it might seem: He notes that many of the enslaved were buried where factories now stand. “You can’t understand America if you don’t understand slavery,” Scott says, “and you can’t understand slavery if you don’t know that slave revolts were constant.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/d5/87d57eac-271a-46cd-84e5-f8e79470721a/opener_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/64/d064457b-db0d-4984-92de-0255962b7167/opener_lfov4.jpg)