Radical Protests Propelled the Suffrage Movement. Here’s How a New Museum Captures That History

Located on the site of a former prison, the Lucy Burns Museum shines a light on the horrific treatment endured by the jailed suffragists

:focal(760x964:761x965)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/b4/62b4ed0c-2fd4-41fe-bfef-077106782979/gettyimages-515586416.jpg)

The first of the “silent sentinel” protests occurred on January 10, 1917. Twelve women, fighting for their right to vote, stood peacefully before the White House with picket signs all day, and every day after that, even as the nation entered the Great War in April. Though other suffragists voiced concern that the protest criticizing President Woodrow Wilson could stain the entire movement as unpatriotic, that did not deter the most resolute picketers.

On June 22, days after the protesters’ presence embarrassed the President in front of Russian dignitaries, the D.C. police arrested suffragist Lucy Burns and her compatriots. A veteran of militant suffragette campaigns in England, Burns had, along with fellow activist Alice Paul, been imprisoned in the United Kingdom, staging hunger strikes and enduring forced feedings in jail; they understood the benefits of being in the national news and staging flashy protests. As part of this new political strategy, they formed their own radical organization, the National Women’s Party, and geared their efforts around headline-grabbing demonstrations.

Burns and the other women were brought to a D.C. jail, then released immediately because local law enforcement could not figure out what to charge them with, or even what to do with the women. As historian and journalist Tina Cassidy explains in Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote, the D.C. authorities were in a difficult position. “One the one hand, the authorities were trying to stop the pickets,” she writes. “On the other, they knew if the women were charged and—worse—sent to prison, they would be instant martyrs.” The police eventually decided the protesters had illegally obstructed traffic.

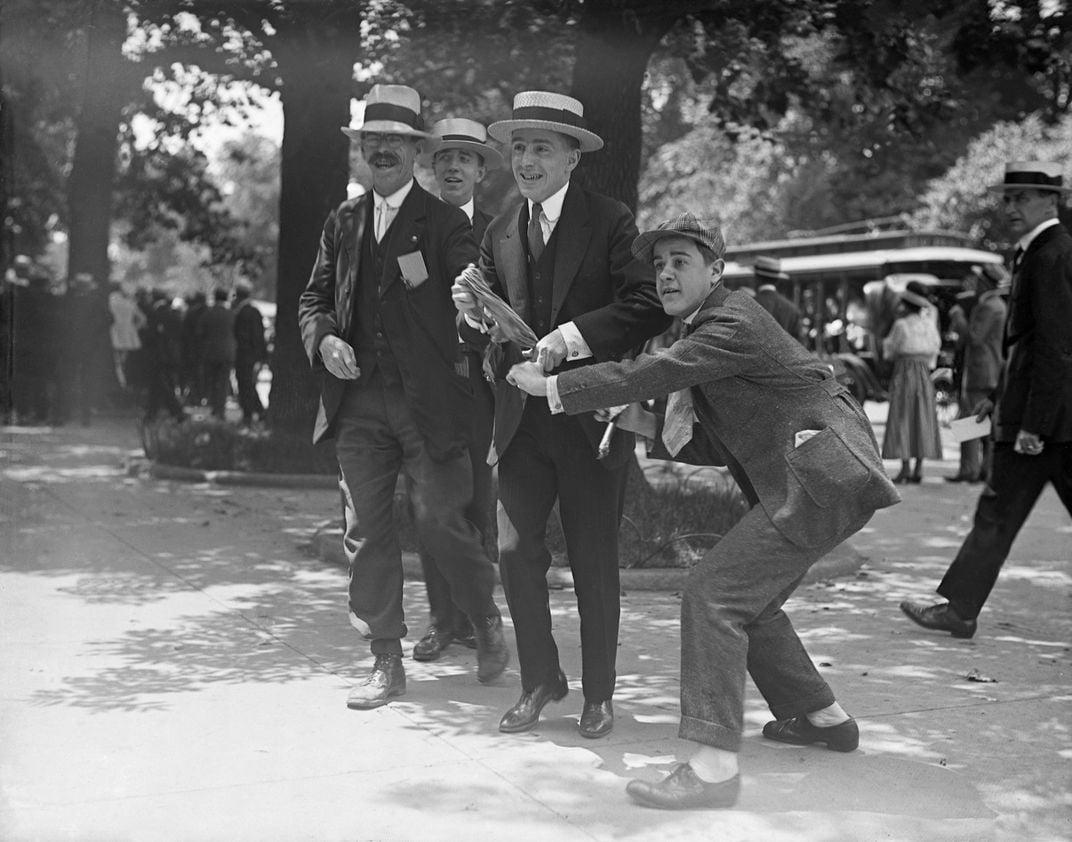

It soon became routine; suffragists would walk with banners to the White House, get arrested, stay in jail briefly when they refused to pay their small fines, then be released. Crowds, anticipating the daily spectacle, gathered to watch. As suffragist Doris Stevens recalled in her suffrage memoir Jailed for Freedom, “Some members of the crowd…hurled cheap and childish epithets at them. Small boys were allowed to capture souvenirs, shreds of the banners torn from non-resistant women, as trophies of the sport.”

The timbre of the suffrage story changed on July 14, Bastille Day, after a month of the charade. This time, a heated trial ensued, with the women serving as their own attorneys. A D.C. judge sentenced 16 suffragists to 60 days in the Occoquan Workhouse, a “progressive rehabilitation” facility for low-level offenders that was part of the sprawling Lorton Reformatory 20 miles south from D.C. in Fairfax County, Virginia. One of the jailed suffragists, Alison Turnbull Hopkins, was married to a friend of President Wilson, John Hopkins, who immediately went to the White House. Two days later, Wilson pardoned the “pickets” (although they refused to formally accept the gesture), and the women walked free.

The women’s sentencing to Occoquan marked a shift in the government’s response to the protest, one which would ultimately lead to what some historians regard as the turning point in the movement towards suffrage. A new museum devoted to telling this story provides a much fuller picture of what happened when women protested for their rights.

* * *

A circumstance of the District’s unique position as the seat of government without any self-rule, the prison had been established a few years prior by an order of Congress. (A District-wide corrections department was not established until the mid-1940s). Administratively, the Occoquan Workhouse at Lorton Reformatory was a federally run prison that functioned as the District’s jail, although early talks considered bringing in prisoners from other parts of the country who might be candidates for “progressive reform” rather than traditional prison.

As Northern Virginia Community College history professor Alice Reagan explains, “Even after the suffragists, it continued to be an issue—why were D.C. prisoners being sent to Virginia? This was one of the issues the suffragists’ lawyers used to get them out.”

Throughout the late summer and fall, suffragists were arrested, held and released by the Metropolitan Police Department, which were befuddled on how to handle this headline-grabbing form of protest that was not a simple criminal matter but one of large political consequence. Stevens, describing one crowd’s reaction to an arrest, evocatively wrote in her propaganda memoirs, “But for the most part an intense silence fell upon the watchers, as they saw not only younger women, but whitehaired grandmothers hoisted before the public gaze into the crowded patrol, their heads erect, their eyes a little moist and their frail hands holding tightly to the banner until wrested from them by superior brute force.”

In all, 72 suffragists served time at Lorton, though Paul, the famous face of these suffragists, was held in solitary confinement in a D.C. prison instead of at Occoquan, where authorities feared she would be a rabble-rousing influence on her followers. But conditions at both locations were harsh, and in September, three suffragists filed an official complaint about the matter with the D.C. authorities.

Together, their affidavits described bad food, including worm-infested meals—"Sometimes, they float on top of the soup. Often they are in the cornbread”—poor hygiene techniques such as being forced to share soap with women with open sores, and physical abuse inflicted by the superintendent and his sons. While the suffragists themselves were not initially beaten, they heard a fellow prisoner being struck in the “booby house.”

Virginia Bovee, a prison matron fired for her sympathy for the women, corroborated their allegations, alleging that “one girl was beaten until the blood had to be scrubbed from her clothing and from the floor.” Horrified at this treatment and claiming that they were political protesters, Paul and others staged hunger strikes, as the British suffragettes had. Prison guards held the women down and force fed by tube through the nose, a brutal process that caused women to bleed from the nose and throat and put them at risk of aspiration pneumonia. In explaining the brutality around the forced feeding but also the impact, the Lucy Burns Museum director Laura McKie says, “If they were willing to stand being force fed, they would have been willing to die.”

The civil disobedience and hunger strikes culminated on November 14, 1917—the “Night of Terror.” According to the accounts of suffragist Eunice Dana Brannan, the harrowing night began when the women asked to see Lorton prison superintendent W.H. Whittaker in an organized group to petition to be treated as political prisoners. Upon meeting his wards, Whittaker threw the first woman to speak to the ground. “Nothing that we know of German frightfulness short of murdering and maiming non-combatants could exceed the brutality that was used against us,” Brannan recounted in the New York Times, prevailing upon the ethnic nationalism of World War I-era America.

She went on to tell how Burns was chained to a cell with her hands over her head all night in “a position of torture” and how Dorothy Day—later the founder of the Catholic Worker Movement—was “thrown back and forth over the back of the bench, one man throttling her while the other two were at her shoulders.” Brannan’s words carried weight among American upper and middle-class men, who might have dismissed younger, single women such as Paul or Burns as radical, hysterical women, but would be less likely to brush off Brannan, the wife of a prominent physician and the daughter of one of President Lincoln’s well-known advisors.

Prison authorities had tried to suppress public awareness of what was going on. From D.C., Paul smuggled out a letter detailing how she’d be transferred to the psychiatric wing as an intimidation tactic. In Lorton, Burns managed to get around the Marines called up from their base at nearby Quantico for the express purpose of stopping leaks. Her note alleged she was “refused privilege of going [to the] toilet” and that she was “seized by guards from behind, flung off my feet, and shot out of the room.”

Some news outlets fell back on sexist tropes and mocked the suffragists’ claims; a Washington Post article described Burns as “worth her weight in wild cats,” Paul as someone who could “throw a shoe twenty fit and hit a window every time” and sympathized that the prison guards had to listen to the “infernal din of 22 suffragettes.” (Associated with militant British activists, “suffragette” was a term critics used for American suffrage advocates, who preferred to be called suffragists.) Within days of the public hearing of their travails, however, a lawyer working for the suffragists obtained a court order for a wellness check. By the end of November—less than two weeks after the Night of Terror—a judge agreed the women at Lorton were subject to cruel and unusual punishment.

With the story of the suffragists playing out in the press, public opinion nationwide began to turn in their favor. By the end of November, all of the prisoners were released. On March 4, 1918, the convictions of the 218 total women arrested over the course of the protests women were voided because the court ruled that “peaceful assembly, under the present statue [was not] unlawful.”

After decades of activism, suffrage was picking up steam. In 1918, Wilson publicly declared support of the suffrage amendment to Congress. By June the next year, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment was ratified by both houses of Congress and passed to the states for ratification.

The fight for suffrage did not start and end with Alice Paul picketing at the White House; organizations such as NAWSA had advocated a state-by-state approach for decades. Adjacent to the former prison site, in a regional park, sits the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial, which states, “When news of the treatment of the suffragists reached the public, it became the turning point in the fight for the right to vote.”

The truth, according to some historians, is a little more complicated. As Robyn Muncy, a historian at the University of Maryland says, “All suffrage activism contributed to the successes of the movement. But pickets were certainly not the only way such attention was won, and the suffrage movement had picked up steam and was winning successes in the states before the pickets started.”

* * *

For all of the suffrage history that happened at Lorton, however, the women’s history component of the site was nearly forgotten—until a prison employee named Irma Clifton devoted herself to preserving its story. Clifton walked through the gates of Lorton Correctional Complex for the first time approximately six decades after the Night of Terror and built relationships with many departments across the sprawling 3,500-acre prison complex as a procurement officer. Clifton took it upon herself to collect stories and objects, setting up an informal museum in her office during her 26 years at Lorton. But while she devoted herself to the complex’s history, Clifton also worried for the prison’s future. Conditions at the prison had deteriorated throughout the 1970s and particularly in the 1980s. By 1997, D.C. arranged to close the prison and transfer the land back to Fairfax County.

As soon as the prison began closing, Clifton advocated for preserving the building. “Without her years of work, vision and energetic promotion, advocacy and direction, the prison would probably have disappeared into development, and its history lost,” says Sallie Lyons, a colleague from the Fairfax County History Commission, which helped Clifton establish the Museum. Concerned that important historical artifacts would be thrown out in the transfer, Clifton reportedly salvaged what she could—even when it wasn’t authorized. Most of the artifacts she saved, like farm equipment or bricks, don’t tell stories of suffrage, although objects such as a lamppost designed like a guard tower speak to the larger history of the site and local interest. But Clifton also took home what would become the museum’s prize possessions—three official prison logbooks from the 1910s—storing them into her garage until she could secure a temporary space for the museum in 2008. These books include the only complete record of the suffragists sent to Occoquan.

Due partially to Clifton’s unfailing advocacy, Fairfax County created a community board to develop an arts center at Lorton, and she became its first chairman in the early 2000s. In 2008, the Workhouse Arts Center opened to the public, a stunning reclamation of a site of criminal justice history. The Arts Center occupies 55 acres of the site; other prison buildings have been turned into luxury apartment buildings.

Clifton lost some preservation battles. The wooden workhouse structure that the first suffragists were held in no longer stands. According to Reagan, who also volunteers at the museum, Clifton was not able to leverage the suffrage history in a complex bureaucratic transfer of lands and buildings that resulted in Fairfax Water’s wastewater treatment plant, which now sits where the suffragists were once held. Though museum staff believe that during the Night of Terror, the prisoners were kept in the still-extant men’s prison, they have no photographs indicating exactly which cells the suffragists were in. But Clifton was determined to have her museum. In 2008, she and a few other volunteers opened up an exhibit in a cellblock studio space, and in the mid-2010s, a donor gave $3 million to renovate Building W-2 and fabricate professional-grade exhibits.

Clifton died of pancreatic cancer in 2019, just months before the museum she had worked towards for 20 years was due to open. With help from Reagan, McKie, a retired employee of the National Museum of Natural History, took on the exhaustive task of developing exhibit content about both the suffragists and the prison’s history as a whole. The Lucy Burns Museum features statues of Burns and Paul that visitors can pose with, farm implements from the prison’s agriculture program and objects like shivs that attest to the violence of the criminal justice system. The prison logbooks and other materials on loan from the District of Columbia government archives are also on display.

At Lorton, white suffragists were placed in close proximity to poor women of color, which made it one of many places in the story of suffrage where racism and classism met in sometimes-ugly ways. Alice Turnbull Hopkins capitalized on her experiences at Lorton with a series of speaking engagements about the indignities she had suffered in jail, relating how she’d been denied a hairbrush and her “luggage.” But the crux of her embarrassment was that “forty-five colored women ate at the tables next to ours, and the colored women shared our workroom and rest room.” For the suffragists, the humiliation of the workhouse was not only unjust arrest. It was that middle-class white women had to suffer the indignities of the American penal system, which included interacting with black women.

Hopkins was not alone in making a media spectacle about her arrest. In 1919, a group of suffragists who had been jailed travelled on a train tour and performance spectacle known as “The Prison Special.” They sang prison songs, wore replicas of prison uniforms and reenacted the brutality of their arrests. For those who preferred literary reenactments, Doris Stevens published Jailed for Freedom in 1920. She wrote about meeting other women in prison—women who had less privilege, faced longer sentences for lesser crimes and weren’t afforded the possibility of presidential pardon. Stevens concluded her account of her first three days in jail by writing, “It was hard to resist digressing into some effort at prison reform.” But despite Stevens’ words, there’s no record of a single suffragist becoming notably interested in prison reform as a result of what she experienced in America’s prisons.

“Ironically, the only suffragist interested in prison reform and abolishing the death penalty was Inez,” says Reagan, referring to Inez Milholland Boissevain, a young lawyer, pacifist and suffragist. Once, while working as a reporter, she asked herself to be handcuffed to share in the experience. Milholland died of tonsillitis, anemia and probable exhaustion before the White House protests began. She was suffrage’s first martyr but never went to jail for the cause.

* * *

Like everything in 2020, nothing has gone according to plan for the Lucy Burns Museum. The Museum had a “soft opening” on January 25 with a May gala planned, which was canceled because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Most of the docents are senior citizens, and few have returned to volunteering during the pandemic. And so despite the centennial, despite the publicity and interest the museum has received this year, it is only open one day per week. At 85 years old herself, McKie remains devoted to telling this story. As she told me, “Women were willing to die to get the vote. That’s the story that needs to be told.”

This summer’s activism, and the force with which it has been met by police, underlines the relevance of the history the museum recounts. The Lucy Burns Museum doesn’t frame suffrage as a story of police brutality; many of its stakeholders are former prison employees, and no former prisoners serve on the board or had curatorial input. Still, the fact remains: Corrections officials treated suffragists with obvious brutality. And the protest techniques of recent months—picketing the White House and hunger strikes in honor of figures such as Breonna Taylor—were techniques innovated by suffragists. As Pat Wirth of the Turning Point Suffrage Memorial said, “Most people know who Susan B. Anthony is, but not much more. They don’t know the suffragists were the first to peacefully protest at the White House. Peaceful protest was then used by the Civil Rights movement, Dr. King and Gandhi, but the suffragists were the first example in America.”

Even at the time, adversaries recognized that what suffragists were doing was innovative. As Judge Edmund Waddill, the judge who delivered the sentence that begrudgingly freed the women after the Night of Terror, said, “If these women, who are highly educated and refined, picket in front of the White House, what will other classes of extremists do if given the same liberties?”