On the Trail of the Warsaw Basilisk

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Basilisk-r-l1-hero.jpg)

Few creatures have struck more terror into more hearts for longer than the basilisk, a monster feared for centuries throughout Europe and North Africa. Like many ancient marvels, it was a bizarre hybrid: a crested snake that hatched from an egg laid by a rooster and incubated by a toad.

The basilisk of legend was rare but decidedly deadly; it was widely believed to wither landscapes with its breath and kill with a glare. The example above comes from a German bestiary dating to the medieval period, but the earliest description was given hundreds of years earlier by Pliny the Elder, who described the monster in his pioneering Natural History (79 A.D.). The 37 volumes of this masterpiece were completed shortly before their author was suffocated by the sulphurous fumes of Vesuvius while investigating the eruption that consumed Pompeii. According to the Roman savant, it was a small animal, “not more than 12 fingers in length,” but astoundingly deadly. “He does not impel his body, like other serpents, by a multiplied flexion,” Pliny added, “but advances loftily and upright.” It was a description that accorded with the then-popular notion of the basilisk as the king of serpents; according to the same mythology, it also “kills the shrubs, not only by contact but by breathing on them,” and splits rocks, “such power of evil is there in him.” The basilisk was thought to be native to Libya, and the Romans believed that the Sahara had been fertile land until an infestation of basilisks turned it into a desert.

The Roman poet Lucan was one of the first authors to describe the basilisk. His work stressed the horrors of the monster’s lethal venom.

Pliny is not the only ancient author to mention the basilisk. The Roman poet Lucan, writing only a few years later, described another characteristic commonly ascribed to the monster–the idea that it was so venomous that any birds that flew over the monster would drop dead from the sky, while if a man on horseback stabbed one with a spear, the poison would flow up through the weapon and kill not only the rider but the horse as well. The only creature that the basilisk feared was the weasel, which ate rue to render it impervious to the monster’s venom, and would chase and kill the serpent in its lair.

The basilisk remained an object of terror long after the collapse of the Roman empire and was popular in medieval bestiaries. It was in this period that a great deal of additional myth grew up around it. It became less a serpent than a mix of snake and rooster; it was almost literally hellish. Jan Bondeson notes that the monster was “the subject of a lengthy discourse in the early-13th-century bestiary of Pierre de Beauvais. An aged cock, which had lost its virility, would sometimes lay a small, abnormal egg. If this egg is laid in a dunghill and hatched by a toad, a misshapen creature, with the upper body of a rooster, bat-like wings, and the tail of a snake will come forth. Once hatched, the young basilisk creeps down to a cellar or a deep well to wait for some unsuspecting man to come by, and be overcome by its noxious vapours.”

The king of snakes also crops up occasionally in the chronicles of the period, and it is in these accounts that we are mostly interested here, since they portray the basilisk not as an interesting ancient legend but as a living creature and a very real threat. Among the principal cases we might note the following:

- According to the Exercitations of Julius Scaliger (1484-1558), in the ninth century, during the pontificate of Leo IV (847-55), a basilisk concealed itself under an arch near the temple of Lucia in Rome. The creature’s odor caused a devastating plague, but the pope slew the creature with his prayers.

- Bondeson reports that in 1202, in Vienna, a mysterious outbreak of fainting fits was traced to a basilisk that had hidden in a well. The creature, which fortunately for the hunters was already dead when they found it, was recovered and a sandstone statue erected to commemorate the hunt.

- According to the Dutch scholar Levinus Lemnius (1505-68), “in the city of Zierikzee–on Schouwen Duiveland island in Zeeland–and in the territory of this island, two aged roosters… incubated their eggs… flogging them they were driven away with difficulty from that job, and so, since the citizens conceived the conviction that from an egg of this kind a basilisk would emerge, they crushed the eggs and strangled the roosters.”

- E.P. Evans, in his massive compilation The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, notes from contemporary legal records that in Basle, Switzerland, in 1474, another old cock was discovered apparently laying an egg. The bird was captured, tried, convicted of an unnatural act, and burned alive before a crowd of several thousand people. Just before its execution, the mob prevailed upon the executioner to cut the rooster open, and three more eggs, in various stages of development, were reportedly discovered in its abdomen.

- At the royal castle at Copenhagen, in 1651, Bondeson says, a servant sent to collect eggs from the hen coops observed an old cockerel in the act of laying. On the orders of the Danish king, Frederick III, its egg was retrieved and closely watched for several days, but no basilisk emerged; the egg eventually found its way into the royal Cabinet of Curiosities.

My friend Henk Looijesteijn, a Dutch historian with the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, adds some helpful details that may help us to understand how the basilisk’s legend persisted for so long. “I have also consulted my own modest library concerning the basilisk,” he writes,

and note that Leander Petzoldt’s Kleines Lexicon der Dämonen und Elementargeister (Munich 1990) discussed the creature. The only historic incident that Petzoldt mentions is the Basle case from 1474, but he adds some detail. The old cock was aged 11 years, and was decapitated and burned, with his egg, on 4 August 1474. A possible explanation for this case is found in Jacqueline Simpson’s British Dragons (Wordsworth, 2001) pp.45-7. Simpson mentions an interesting theory about so-called egg-laying cock, suggesting they were in reality hens suffering from a hormone imbalance, which it seems is not uncommon and causes them to develop male features, such as growing a comb, taking to crowing, fighting off cocks, and trying to tread on other hens. She still lays eggs, but these are, of course, infertile. An intriguing theory, I think, which may explain the Basle, Zierikzee and Copenhagen cases.

By far the best known of all basilisk accounts, however, is the strange tale of the Warsaw basilisk of 1587, which one sometimes sees cited as the last of the great basilisk hunts and the only instance of an historically verifiable encounter with a monster of this sort. The origins of the story have hitherto been rather obscure, but Bondeson gives one of the fullest accounts of this interesting and celebrated incident:

The 5-year-old daughter of a knifesmith named Machaeropaeus had disappeared in a mysterious way, together with another little girl. The wife of Machaeropaeus went looking for them, along with the nursemaid. When the nursemaid looked into the underground cellar of a house that had fallen into ruins 30 years earlier, she observed the children lying motionless down there, without responding to the shouting of the two women. When the maid was too hoarse to shout anymore, she courageously went down the stairs to find out what had happened to the children. Before the eyes of her mistress, she sank to the floor beside them, and did not move. The wife of Machaeropaeus wisely did not follow her into the cellar, but ran back to spread the word about this strange and mysterious business. The rumour spread like wildfire throughout Warsaw. Many people thought the air felt unusually thick to breathe and suspected that a basilisk was hiding in the cellar. Confronted with this deadly threat to the city of Warsaw, the senate was called into an emergency meeting. An old man named Benedictus, a former chief physician to the king, was consulted, since he was known to possess much knowledge about various arcane subjects. The bodies were pulled out of the cellar with long poles that had iron hooks at the end, and Benedictus examined them closely. They presented a horrid appearance, being swollen like drums and with much-discoloured skin; the eyes “protruded from the sockets like the halves of hen’s eggs.” Benedictus, who had seen many things during his fifty years as a physician, at once pronounced the state of the corpses an infallible sign that they had been poisoned by a basilisk. When asked by the desperate senators how such a formidable beast could be destroyed, the knowledgeable old physician recommended that a man descend into the cellar to seize the basilisk with a rake and bring it out into the light. To protect his own life, this man had to wear a dress of leather, furnished with a covering of mirrors, facing in all directions.

Johann Pincier, the author who first put an account of the Warsaw basilisk in print at the turn of the seventeenth century. From a line engraving of 1688.

Benedictus did not, however, volunteer to try out this plan himself. He did not feel quite prepared to do so, he said, owing to age and infirmity. The senate called on the burghers, the military and police but found no man of sufficient courage to seek out and destroy the basilisk within its lair. A Silesian convict named Johann Faurer, who had been sentenced to death for robbery, was at length persuaded to make the attempt, on the condition that he be given a complete pardon if he survived his encounter with the loathsome beast. Faurer was dressed in creaking black leather covered with a mass of tinkling mirrors, and his eyes were protected with large eyeglasses. Armed with a sturdy rake in his right hand and a blazing torch in his left, he must have presented a singular aspect when venturing forth into the cellar. He was cheered on by at least two thousand people who had gathered to see the basilisk being beaten to death. After searching the cellar for more than an hour, the brave Johann Faurer finally saw the basilisk, lurking in a niche of the wall. Old Dr. Benedictus shouted instructions to him: he was to seize it with his rake and carry it out into the broad daylight. Faurer accomplished this, and the populace ran away like rabbits when he appeared in his strange outfit, gripping the neck of the writhing basilisk with the rake. Benedictus was the only one who dared examine the strange animal further, since he believed that the sun’s rays rendered its poison less effective. He declared that it really was a basilisk; it had the head of a cock, the eyes of a toad, a crest like a crown, a warty and scaly skin “covered all over with the hue of venomous animals,” and a curved tail, bent over behind its body. The strange and inexplicable tale of the basilisk of Warsaw ends here: None of the writers chronicling this strange occurrence detailed the ultimate fate of the deformed animal caught in the cellar. It would seem unlikely, however, that it was invited to the city hall for a meal of cakes and ale; the versatile Dr. Benedictus probably knew of some infallible way to dispose of the monster.

Now, this seems strange and unbelievable stuff, because, even setting aside the Warsaw basilisk itself, there are quite a few odd things about this account which suggest some intriguing puzzles concerning its origins. For one thing, Renaissance-era knife sellers were impoverished artisans–and what sort of artisan could afford a nursemaid? And whoever heard of a knife seller with a name like Machaeropaeus? It’s certainly no Polish name, though it is appropriate: it’s derived from the Latin “machaerus”, and thence from the Greek “μάχαιρα”, and it means a person with a sword.

The first puzzle, then, is this: the only sort of person likely to be mooching around central Europe with a Latin monicker in the late 16th century was a humanist–one of the new breed of university-educated, classically influenced scholars who flourished in the period, rejected the influence of the church, and sought to model themselves on the intellectual giants of ancient Greece and Rome. Humanists played a vital part in the Renaissance and the academic reawakening that followed it; they communicated in the scholars’ lingua franca, Latin, and proudly adopted Latin names. So whoever the mysterious Polish knife seller lurking on the margins of this story may have been, we can be reasonably confident that he himself was not a humanist, and not named Machaeropaeus. It follows that his tale has been refracted through a humanist lens, and most likely put into print by a humanist.

Bondeson, a reliable and careful writer, unusually gives no source for his account of the Warsaw basilisk, and my own research traced the story only back as far as the mid-1880s, when it appeared in the first volume of Edmund Goldsmid’s compilation Un-natural History. This is a rare work, and I’m certainly not qualified to judge its scholarship, though there’s no obvious reason to doubt that Goldsmid (a Fellow of both the Royal Historical Society and the Scottish Society of Antiquaries) is a reliable source. According to Un-natural History, anyway, the Warsaw basilisk was chronicled by one George Caspard Kirchmayer in his pamphlet On the Basilisk (1691). Goldsmid translates this work and so gives us a few additional details–the implements used to recover their bodies were “fire-hooks,” and Benedictus, in addition to being the King’s physician, was his chamberlain as well. As for Faurer, the convict, “his whole body was covered with leather, his eyelids fastened down on the pupils a mass of mirrors from head to foot.”

Georg Kirchmayer, who provided the vital link between Pincier’s obscure work and modern tellings of the basilisk legend in a pamphlet of 1691.

Who, then, was Goldsmid’s “George Caspard Kirchmayer”? He can be identified as Georg Kaspar Kirchmayer (1635-1700), who was Professor of Eloquence (Rhetoric) at the University of Wittenberg-Martin Luther’s university- in the late 17th century. With Henk’s help, I tracked down a copy of On the Basilisk and found that Kirchmayer, in turn, gives another source for his information on the Warsaw case. He says he took his information from an older work by “D. Mosanus, Cassellanus and John Pincier” called (I translate here from the Latin) “Guesses, bk.iii, 23″. The Latin names are a bit of a giveaway here; the mysterious Guesses turns out to be, as predicted, a humanist text, but it is not–a fair bit of trial and error and some extensive searching of European library catalogues reveals–a volume titled Conectio (‘Guesses’). The account appears, rather, in book three of Riddles, by Johann Pincier (or, to give it its full and proper title, Ænigmata, liber tertius, cum solutionibus in quibus res memorata dignae continentur, published by one Christopher Corvini in Herborn, a German town north of Frankfurt, in 1605.)

The author named by Kirchmayer can also be identified. There were actually two Johann Pinciers, father and son, the elder of whom was pastor of the town of Wetter, in Hesse-Kassel, and the younger the professor of medicine at Herborn–then also part of the domains of the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel–and later in neighboring Marburg. Since Ænigmata was published in Herborn, it seems it was the younger of the two Pinciers who was actually the author of the book, and hence of what appears to be the original account of the Warsaw story, which–a copy of his work in the Dutch National Library in The Hague reveals– appeared on pp.306-07.

This, of course, raises another problem, for the edition of the work we have today has a pagination that bears no resemblance to that consulted by Kirchmayer; it’s possible, therefore, that the version he relied on contained a variant, and in fact the story as given in the edition consulted at the Hague is significantly less detailed than that given in On the Basilisk. This means that it is not possible to say whether or not the Wittenburg professor elaborated the tale himself in his retelling. Pincier’s close connection with Hesse-Kassel, on the other hand, is confirmed by his dedication of the whole volume to Moritz the Learned (1572-1632), the famously scholarly reigning Landgrave of the principality at the time Ænigmata was published.

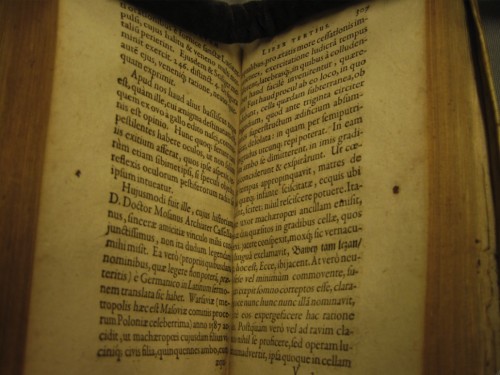

The Dutch National Library’s copy of Pincier’s Ænigmata (1605), opened at the pages that discuss the appearance of the Warsaw basilisk 18 years earlier. Photo courtesy of Henk Looijesteijn.

The identity of Kirchmayer’s “D. Mosanus” is more of a puzzle. He certainly wasn’t the co-author of Ænigmata, and exactly how his name came to be connected to the tale of the Warsaw basilisk is something of a mystery, but–taking Hesse-Kassel as a clue–it’s possible to identify him as Jakob Mosanus (1564-1616), another German doctor-scholar of the 17th century–the D standing not for a Christian name but for Dominus, or gentleman–who was personal physician to Moritz the Learned himself. This Mosanus was born in Kassel, and this explains the appearance of the word “Cassellanus” in Kirchmayer’s book–it’s not a reference to a third author, as I, in my ignorance, first supposed, but simply an identifier for Mosanus. And, whether or not the good doctor wrote on the basilisk, it’s well worth noting that he was–rather intriguingly–both a noted alchemist and a suspected Rosicrucian.

It’s worth pausing for a moment here to point out that the mysterious and controversial creed of Rosicrucianism was born, supposedly, in the same small principality of Hesse-Kassel not long after the publication of Ænigmata–very possibly as an offshoot of the same humanist initiatives that inspired Pincier, and in the similar form of an anonymous pamphlet of indeterminate origin purporting to be nothing less than the manifesto of a powerful secret society called the Order of the Rosy Cross. This contained a potent call for a second reformation – a reformation, this time, of the sciences – which promised, in return, the dawning of a new and more rational golden age.

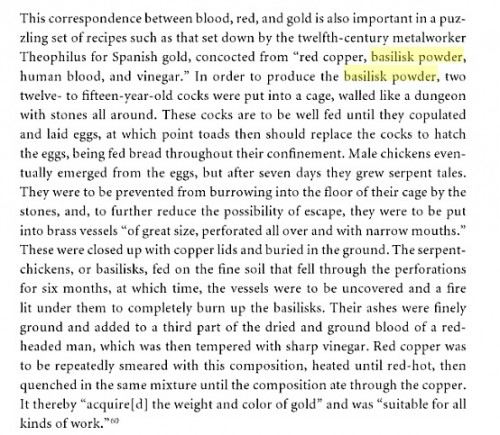

An extract from Klein and Sperry’s Materials and Expertise in Early Modern Europe describing the convoluted process of manufacturing “basilisk powder”. Double click to read in a higher definition–and be sure to inform us if you try it and the method works.

All this makes Mosanus’s connections particularly interesting, because it suggests that he would certainly have been interested in basilisks. Basilisk powder, a substance supposedly made from the ground carcass of the king of snakes, was greatly coveted by alchemists, who (Ursula Klein and E.C. Spary note) believed it was possible to make a mysterious substance known as “Spanish gold” by treating copper with a mix of human blood, vinegar and the stuff. I conclude, therefore, that the two men identified by Kirchmayer as his authorities for the Warsaw tale both enjoyed the patronage of Moritz the Learned, may perhaps have been collaborators, and were certainly close enough in time and place to the Warsaw of Kings Stefan I and Sigismund III to have sourced their story solidly. In the close-knit humanist community of the late 16th century it’s entirely possible that one or both of them actually knew Benedictus–another Latin name, you’ll note – the remarkably learned Polish physician who is central to the tale.

Does this mean that there is anything at all to the story? Perhaps yes, probably no–but I would certainly be interested to know a good deal more.

Sources

Jan Bondeson. The Fejee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999; E.P. Evans. The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals. London: W. Heinemann, 1906; Edmund Goldsmid. Un-Natural History, or Myths of Ancient Science: Being a Collection of Curious Tracts on the Basilisk, Unicorn, Phoenix, Behemoth or Leviathan, Dragon, Giant Spider, Tarantula, Chameleons, Satyrs, Homines Caudait, &c… Now First Translated from the Latin and Edited... Edinburgh, privately printed, 1886; Ursula Klein and E.C. Spary. Materials and Expertise in Early Modern Europe. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2009; Johann Pincier. Ænigmata, liber tertius, cum solutionibus in quibus res memorata dignae continentur ænigmatum. Herborn: Christopher Corvini, 1605.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)